Learn in the following article everything related to the History of the Otomi, its culture, tradition and religious practices. The Otomi are considered one of the most important and expanding Mexican ethnic groups of all time.

history of the Otomi

The Otomi played a fundamental role in the prehistory and ancient history of Mexico, despite the fact that many try to downplay it. This group had made great contributions to the development of culture and tradition. In the following article we will learn a little more about the History of the Otomi.

Throughout its history, Mexico has had many peoples and ethnic groups that have left their mark on cultural and popular issues. One of the Mexican ethnic groups with the greatest expansion and culture up to our times is precisely Los Otomíes. If you want to learn more about their culture, tradition and customs, we invite you to stay tuned for the following article.

What are the Otomis?

Before learning about their history, it is important to describe who the Otomies are. It is a native group or population that occupies an interrupted space in the focus of Mexico. It is linguistically related to the rest of the Ottoman-speaking peoples, whose descendants have occupied the neovolcanic support from several millennia of early Christian time.

Currently this Mexican group is occupying a divided area that goes from the north of Guanajuato to the east of Michoacán and to the southeast of Tlaxcala, despite the fact that the largest number of Otomi today live in the states of Hidalgo, Mexico and Querétaro. They have a large number of inhabitants according to censuses carried out by institutions in the country.

The National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples in Mexico indicated that the Otomí people were made up of about 646.875 thousand inhabitants in the Mexican Republic for the year 2000. That figure makes it the fifth largest native people in Mexican territory. .

Of those approximately 646 people who were part of the Otomi people, a little more than half spoke Otomi. It is important to point out that the Otomí language presents a high degree of internal diversification, so that the inhabitants of one diversity usually have problems matching those who speak another language.

For this reason, the names by which the Otomi call themselves are usually quite diverse. Among the main names we find:

- ñätho (Toluca Valley)

- hñähñu (Valley of the Mezquital)

- ñäñho (Santiago Mexquititlán in the South of Querétaro)

- ñ yürü (Northern Sierra of Puebla, Pahuatlán)

These four names are just some of the terms that the inhabitants of the Otomí people use to call themselves in their own languages, although it is common that, when they speak in Spanish, they use the Otomí ethnonym, of Nahuatl origin.

In a few words, we could say that the Otomies are described as an indigenous people that is currently installed in a discontinuous territory in the center of Mexico. They are part of the Otomanguean and Otomí-Pame linguistic families, words used by each people according to the region they inhabited.

Homes

One of the things that most characterizes the people of Los Otomíes are their attractive and particular homes in which they live. Most of these people live in rectangular, narrow infrastructures that are usually very humble and of low quality. A good part of the Otomi dwellings are low-rise and quite small in size.

The houses of Los Otomíes also have roofs made of maguey leaves, which is not very resistant. Just as it happened with the rest of the pre-Hispanic dwellings, the houses of Los Otomíes did not have much height. They are low-rise buildings, with a single door and no windows.

The inhabitants of this ethnic group use various materials to make their houses. Among the main materials they use are maguey leaves, tejamanil, adobe and stone, the roofs of these houses were often made of tiles, leaves, grass or cardboard sheets.

These houses have rooms, which were mostly used as bedrooms, cellars, kitchens and even to store farmyard animals to protect them from the cold, rain and other wild animals. The hygiene measures that are maintained inside these houses are few, if not scarce.

Clothing

But not only the houses are part of the Otomi tradition, clothing also plays an essential role within the culture of this group or ethnic group. Let's talk first about the clothing worn by the women who belong to this town. The women use a wool chincuete, which almost always has dark colors.

They also wear a blouse designed with floral and animal motifs embroidered on the neck and arms. The women of the Otomíes also use an embroidered girdle to hold their clothing. Women's clothing is very striking compared to men's, which is usually a bit simpler.

The men who are part of the town of Los Otomíes have been adapting to new ways of dressing, they have even modified their traditional garments for those that they sell in their towns. Older men usually wear a shirt made of an embroidered blanket, with which they participate in parties and dances. Embroidery is usually done on the sides of the chest and on the sleeve cuffs.

It could be said that the way men dress is quite similar to that of the peasants of the region. Otomi men do not care so much about their clothing, beyond what tradition or culture allows them. Now, in the case of women, clothing is more striking and they try to take care of every detail.

In the case of women, it is the elderly who generally have the custom of using the traditional blanket blouse with colored embroidery on the neck and sleeves. Over the blouse they usually wear a quexquémitl or failing that, a rebozo. It is important to clarify that the way of dressing can present some changes depending on the region in which each Otomi community lives.

Food

The Otomi were also characterized by their way of eating. They didn't eat everything there was, but some special things. For example, their diet was based mainly on corn. This item was used to prepare many dishes, such as tortillas, tamales, atoles, as well as cooked or roasted corn.

Apart from corn, the Otomíes also eat other vegetable products such as nopales, prickly pear, broad beans, pumpkins, chickpeas, beans and peas. In its typical dishes, the presence of the different kinds of chili cannot be missing, considered one of the ingredients most used by the Otomi in their diet.

A good part of the Otomies also had the habit of consuming milk, legumes and animal fats. In the case of meat, it is important to mention that they only consumed it when special activities such as parties or dances were carried out, and they also ate it in small quantities.

Within the diet of the Otomíes, the use of herbs such as mote tea, mint or chamomile is also common. Although they do not consume much, the people of this town also tend to eat some wild fruits that serve as a complement to their gastronomy. The consumption of pulque is also common.

As we have been able to notice, the diet of the Otomi is quite healthy and different from that of the rest of the communities or organizations. The vast majority of their basic food consists of corn tortillas, one of the items that is most frequently produced in these communities.

But their gastronomic dishes are not only focused on corn, despite being the main product of their meals. In the diet of the Otomi, other elements also stand out, such as beans, eggs, quelites, quintaniles, malva, cheese and on certain special occasions, they usually consume animal protein such as chicken or beef.

They are very demanding when it comes to food, but when it comes to the drinks they consume, the Otomi also have their typical products. Among the Otomi peoples there is a tradition or custom of drinking a lot of coffee, as well as atole and tea, which they prepare based on different herbs and pulque.

Origin and History

There are many versions about the origin and history of the Otomies. Most historians who have focused on studying the evolution of this ethnic group say that these Indians were the first people to inhabit the Valley of Mexico, where Mexico City is located today, however they were expelled by the Indians. Mexica or Aztecs

The Otomi were also part of the groups present in Teotihuacán, considered one of the most influential and largest ancient cities in Mexico, which was a multi-ethnic center at the time, and Tula, which is where they were given land to form the kingdom of Xaltocan. from King Xolotl (XNUMXth century).

Eventually, the Otomi kingdom came to an end during the XNUMXth century when the Mexica and their alliances conquered the kingdom. At that time, the people who were part of the Otomi people were obliged to pay a tribute to the Mexica people as their empire grew.

Over time, the Otomi people were forced to relocate to the less desirable lands to the east and south. However, beyond this reality, some Otomi were still based near Mexico City, although the largest number of Indians settled in areas near the Mezquital Valley in Hidalgo, the highlands of Puebla, areas between Tetzcoco and Tulancingo. , and even Colima and Jalisco.

Historians have also agreed that the Otomi played a fundamental role in the Mexica civilization. The Mexica, who were the society that dominated most of the Mesoamerican territory at the time of the Spanish conquest, took many traditions and customs from the Otomi.

However, the Mexica are suspected of burning and trying to eliminate certain aspects of their civilization in order to be able to manipulate much of their own history. There was even a debt with the Otomí that is believed to have been erased from the history of the Mexica.

For all those reasons, the Otomi were singled out by the Mexica as a civilization of low life and that many negative implications. The Otomi began to be seen as a bad influence, not only by the Mexica but even by the Spanish conquerors who arrived in Mexican territory.

The consequences of this misperception about the Otomi were not long in coming, so much so that in recent years the descendants of this ethnic group have been forced to change their native language due to the reputation created by the Mexica. It is important to note that the Otomi lived in rugged mountainous terrain.

Thanks to that, a significant number of inhabitants could live the life that seemed best to them, unlike the indigenous population near Mexico City that was plagued by conquering invasions. For this reason, many of the religious traditions and beliefs of the Otomi were maintained from the pre-conquest period.

This was more common among the Sierra Ñähñu, where some Augustinian friars in the XNUMXth century recorded that a good part of the Otomi kept their religious beliefs and were difficult to extract from them. So much was their roots in these beliefs that today many of the religious images of the Otomi are still present there.

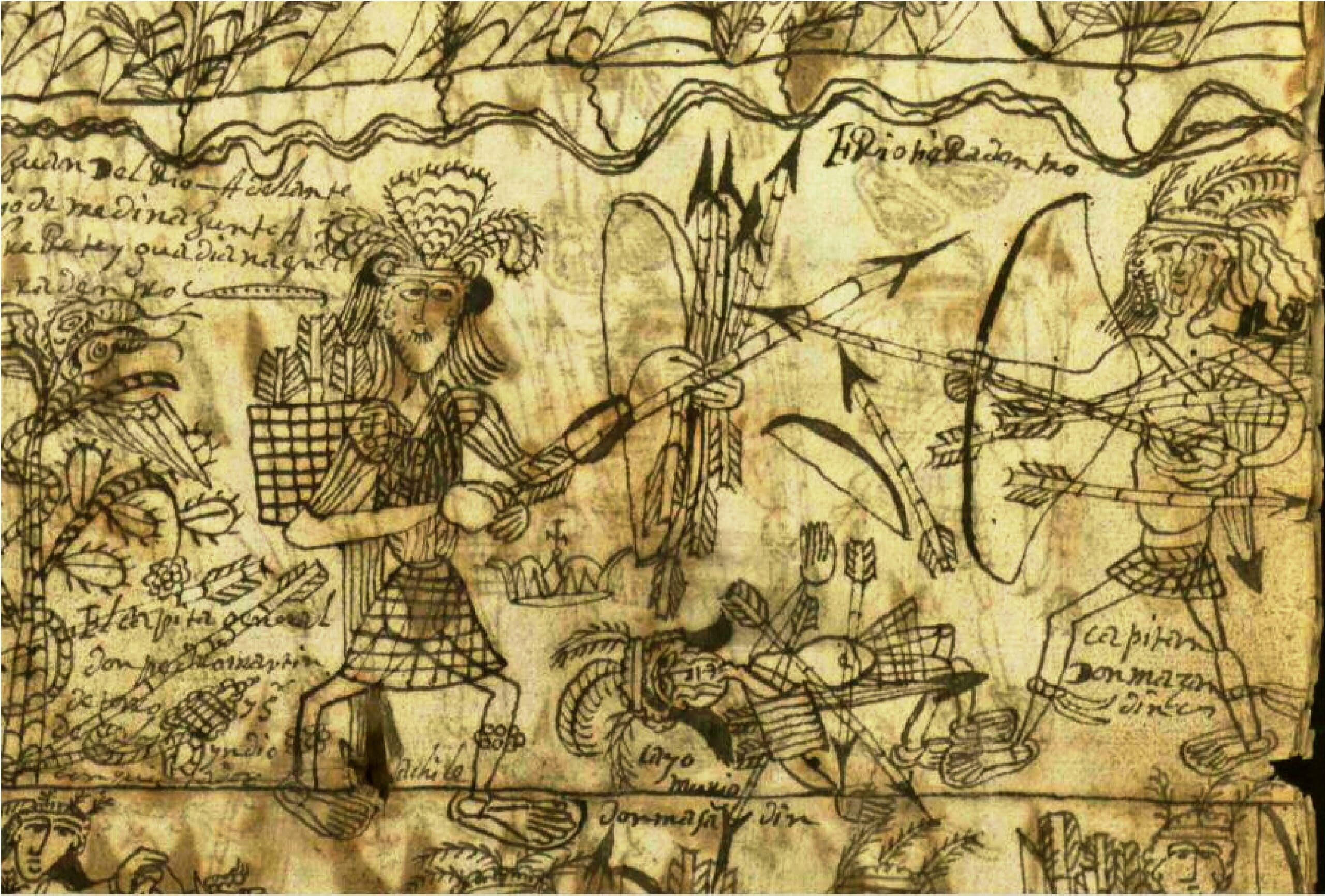

The history of the Otomies also teaches us that a good part of this ethnic group lived in the state of Tlaxcala. It was in that town where they joined the forces of the conqueror of Spanish origin Hernán Cortés, in order to battle against the Mexicas, whom they were finally able to defeat.

The defeat of the Mexicas gave the Otomies the opportunity to expand again in many areas of the country. They proceeded to found the city of Querétaro, in addition to settling in different cities of the state currently known as Guanajuato.

The Otomíes worked hand in hand with the Spanish for a long time and that caused a significant number of these Indians to convert to Roman Catholicism, however, at the same time they maintained their ancient customs. During its colonization, the Otomí language spread to many other states such as Guanajuato, Querétaro and the Mezquital Valley region.

The Mezquital Valley region included the states of Puebla, Veracruz, Hidalgo, and the Toluca Valley along with Michoacán and Tlaxcala, where most belonged as farmers. In the Mezquital valley, the fertile did not have all the equipment to work in agriculture, because the land was dry. For this reason, many Otomí concentrated as day laborers and depend largely on the maguey-based drink, pulque.

At first, the Spanish decided to prohibit the consumption of the drink, but they quickly tried to manage a business through its production, which led the Otomi to use the drink only for their own consumption. The Otomi also played an important role in the Mexican War of Independence.

During that battle, the Otomí supported the rebellion, mainly because they had in mind the intention of recovering their lost lands, which had been taken from them under the encomienda system. Nonetheless, the land was given to the descendants of the original Spanish who had claimed the land with the Otomi people who were hired as helping hands.

During the 1940-50 era, the authorities who were at the head of the government made many promises to the indigenous communities, to whom they promised to offer help in areas such as education and the economy, however they remained only promises, since they never they fulfilled what was promised.

Failing to see promises kept, indigenous communities were forced to continue farming and working as laborers within their smaller subsistence economy within a larger capitalist economy where indigenous peoples could be subjected to exploitation by those in control. the economy.

It is no secret to anyone that since Mexican independence was achieved, the authorities of that country have maintained a posture of worship towards pre-Hispanic history and the works of the Aztecs and the Mayans, however they have left the living indigenous peoples in oblivion, like the Otomi, who are not taken into account with the same importance.

Until a few years ago, the Otomis were not properly attended by the authorities. This was the case until a recent anthropologist began to investigate their ancient way of life. As a consequence, the Mexican government has declared itself a multicultural state that serves to help many of its indigenous populations, such as the Otomi.

Certainly a good part of the current descendants of the Otomi have begun to move to other regions, there is still an indication of their ancient culture present today. In some areas of Mexico, such as Guanajuato and Hidalgo, Otomí prayer songs are heard and elders share stories of young people who understand their mother tongue.

Beyond the indisputable influence of the Otomi people in Mexican culture and history, the truth is that little attention has been paid to Otomi culture, especially in educational spaces, where very little is currently said about its history and evolution. For this reason, many Otomi descendants are unaware of aspects related to their own cultural history.

Once the Spaniards arrived in Mexican territory, the Otomi found a great opportunity to free themselves from the Aztec empire. It was for this reason that a good part of the Otomi communities offered their full support to the Spanish conquerors, although there was a sector that did not want to support the conquerors.

Those Otomí, who were reluctant to support the intentions of the Spanish conquerors, retreated into the mountains, a displacement that was accentuated when an epidemic of smallpox broke out. Already during the XNUMXth century, the occupation of their lands, apart from the establishment of a mission, caused situations of instability.

After the colonization of the mountains inhabited by the Chichimecas, it was intended to force the nomads to adopt new practices and lifestyles, moving from hunting to agriculture. The missionaries made a titanic effort to try to convince the nomads, in a peaceful way, while introducing them to Catholicism.

Already during the eighteenth century, the reality of the Otomies began to be increasingly difficult. A large part of them were expelled to more arid and marginal areas. The independence movement, far from helping them, caused more instability among the Otomi people, especially from an economic point of view.

The latifundios were divided into small properties for the criollos and mestizos, and the Indians continued as peons. Mining production in the state of Hidalgo was notably affected, to the point of entering a deep crisis, a situation that forced many workers to emigrate to other areas, especially Huasteca and Mineral del Monte.

This scenario also caused a decrease in the registration of the male population among the Otomi peoples. During the most complex years of the war, many Otomi were forcibly concentrated in Tulancingo. Despite all the crisis and exploitation to which they were subjected, the Otomi never lost their language, on the contrary, they created their own songs, dances, crafts and their worldview.

Characteristics of the Otomi

Within Los Otomíes we find several groups, but there are two that are considered the most popular. These are:

- The Altiplano (or Sierra) Otomí. This is the group that lives in the mountains of La Huasteca, Sierra Otomí usually identifies as Ñuhu or Ñuhu, depending on the dialect they speak.

- The Otomi Mosque. This group lives in the Mezquital Valley in the eastern part of the state of Hidalgo, and in the state of Querétaro. Mezquital Otomí self-identifies as Hñähñu.

It is important to note that there are smaller Otomi populations that live in other areas of Mexico, especially in the states of Puebla, Mexico, Tlaxcala, Michoacán and Guanajuato. The Otomí language which belongs to the Otopame branch of the Oto-Manguean linguistic family is spoken in many different varieties, some of which are not mutually intelligible.

One of the earliest complex cultures of Mesoamerica, the Otomi are believed to have been the original inhabitants of the central Mexican highlands before the arrival of the Nahuatl inhabitants around c. 1000 CE, but were gradually replaced and marginalized by the Nahua peoples.

During the colonial period of New Spain, the Otomi peoples were mainly characterized by collaborating with the Spanish conquerors as mercenaries and allies, which gave them the opportunity to expand into many territories where they had once been inhabited by semi-nomadic Chichimecas, for example Querétaro and Guanajuato.

Among one of the main characteristics of the Otomies was their religious tradition and customs. They generally had the custom of worshiping the moon as their greatest deity, and even in modern times a large number of Otomi populations have become involved with shamanism and have pre-Hispanic beliefs such as Nagualism.

The Otomi were also characterized by cultivating and consuming corn, beans and squash, as was the case with most of the sedentary peoples of Mesoamerica. Maguey was also an important cultigen used for the production of alcohol and fiber.

It is no secret to anyone that these indigenous people rarely consume common foods that are generally considered important to maintain a healthy pattern.

Despite that, they have a good diet eating tortillas, drinking pulque and eating most of the fruits available around them. The Otomi have been characterized as a hardworking people, despite the harsh working conditions in which they carry out their activities.

This was demonstrated by a nutritional study carried out on the Otomi peoples located in the Mezquital Valley of Mexico between the years 1963 and 1944. In that report it was said that despite the arid climate and the land not suitable for agriculture without risk, the Otomi depended mainly from the production of maguey.

With the maguey they carry out many activities, among them to produce fabric fibers and "pulque", a traditional unfiltered fermented juice that was widely important in the economy of the Otomi and their nutrition. However, this practice has lowered its level due to its new large-scale production.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AaOyCN86Ess

“The maguey plant depended so much on the huts being built with the leaves of the plants. During this time, most of the region was very undeveloped and most crops had a very low rate of return. Settlement areas are sometimes mistaken for places far from habitation.”

Regarding their economy, it is important to mention that the Otomi were fundamentally characterized by being blacksmiths and by trading valuable metal articles with other indigenous confederations, including the Aztec Triple Alliance. Among some of their craft work were ornaments and weaponry.

Regarding the social organization within the Otomíes, it is important to highlight several aspects. The first thing we must say is that the social organization among them can change significantly depending on the region of settlement. In this way we can see that there are regions where the basic unit of the community is the nuclear family, while in other regions it is the extended family.

But there is one aspect that all communities share, depending on the settlement region in which they are found, and that is the fact of the main authority, which in most cases is represented by the father. It is the father, accompanied by the mother, who has the responsibility of educating, teaching and transmitting cultural customs and habits to their children and other members of the community.

Each of the members of an Otomi family plays a special role and everyone knows the work they have to do. In the case of men, they are mainly responsible for cultivating the land, building and repairing houses, caring for livestock, as well as participating in community work.

The women of the Otomi peoples take care of very different but equally important things. They are generally in charge of preparing food, keeping homes in perfect condition, washing clothes and raising domestic animals in each community.

One of the characteristics of the Otomies is that when the time comes to sow and harvest, not only the men get involved, but all the members of the family usually participate in this activity. A very important factor within the Otomi peoples has to do with the figure of marriage.

For them, marriage plays a very important and vital role, but in addition to marriage, a highly respected relationship is established with the compadrazgo that arises at baptism and is considered the most important symbolic bond among the Otomi inhabitants.

The task is also considered one of the most important activities within the Otomi, apart from being mandatory. Due to migration, the man who is outside pays someone else to do the work. In case this man refuses to pay the other person, then he risks losing all his rights as a member of the community.

The Otomi are also characterized by having their own beliefs regarding illnesses. They classify the origin of diseases at two different levels. On the one hand there are diseases of natural origin, but they also have the belief that there are certain pathologies that have a supernatural origin.

Natural diseases, according to the Otomi, are the most common and to combat them they do so through allopathic medicine. Something very different happens with the so-called supernatural diseases, which, according to their beliefs, are part of the group's worldview.

According to the Otomi tradition, the origins of illnesses have a magical-religious basis. In order to find a cure for these diseases, they must attend traditional therapists, such as midwives and bonesetters, herbalists and healers, who can heal them of their ailments.

Many Otomi families also turn to natural plants to cure their illnesses. They almost always use medicinal plants to heal each of their presented pathologies. Domestic medicine has also played an important role in maintaining the biological-social balance of the community. The use of herbalism is very common.

Current demographics and population

Currently, Otomi dialects are spoken by around 239,000 speakers, of which 5 to 6 percent are monolingual, in widely dispersed districts. Currently it is believed that a large part of the inhabitants of this ethnic group are installed in the Valle de Mezquital region of Hidalgo and in the southern portion of Querétaro. Several municipalities there have concentrations of Otomi speakers as high as 60-70 percent.

Thanks to the fact that many Otomi speakers have emigrated in recent times, today it is possible to find their presence in many areas of Mexican territory, even in the United States. In the second half of the XNUMXth century, speaking populations began to increase again, although at a slower rate than the general population.

While the absolute number of Otomi speakers continues to increase, their number relative to the rest of the Mexican population is declining. The Otomi language could currently be considered at risk of extinction, despite the fact that they are a vigorous people and that children learn the language through natural transmission in many areas, such as in the Mezquital Valley and in the Highlands.

According to various population studies carried out in recent years, it is believed that the largest number of the Otomi population is located in the state of Hidalgo, specifically in the well-known Valle del Mezquital. There are some municipalities in the western region that have more Otomi population than others.

Among the main municipalities with the largest number of inhabitants of this ethnic group are Tlanchinol, Cardonal, Tepehuacán de Guerrero, San Salvador, Santiago de Anaya and Huazalingo. For their part, the municipalities of the westernmost region of Hidalgo with the highest population density of Otomí are Huehuetla, San Bartolo and Tenango de Doria.

It is also said that the state of Mexico currently ranks second in terms of Otomi population. Most of these inhabitants are concentrated in the municipalities of Toluca, Temoaya, Acambay, Morelos and Chapa de Mota. In the state of Veracruz there is also an Otomi presence, especially in the Huasteca region.

In other Mexican states there is also an Otomí presence, although in a lower percentage, such is the case of Michoacán. It has been said that the drawings and designs of the animals, birds and other figures were inspired by cave paintings. This particular embroidery is also known as Tenango embroidery.

Tradition indicates that it is the men who are usually in charge of making the drawings of the designs on the white or white cloth so that later the women are in charge of the embroidery process. The figures are stories or typical representations or life that has been taught from generation to generation.

Speaking of the Otomi population is referring to their authorities. Within these towns, the political organization is based around the constitutional town hall, whose backbone is the political center, with the municipal president at the head. At the populated level, the positions may vary and in ascending order of hierarchy they are:

- Mensajero

- Sheriff

- Police

- Secretary

- assistant judge

It is also important to mention that the Otomi maintain most of the traditional religious positions, such as mayordomos and prosecutors, although it is necessary to clarify that the election is currently voluntary. Community work, better known as "faena", is still a fairly common practice among most Otomi communities.

Otomi Legends

It is no secret to anyone that the Aztec culture is considered by many to be one of the most legendary and mysteriously tragic in all of Mesoamerica, partly because of the short time it existed in the annals of history and the destruction of society by of the Spanish conquerors.

According to the appreciation of many experts, Aztec society was a complex and interlocking system of hierarchies and social divisions. In those years, most people were ruled by the fear of violent and vengeful gods, while civilization depended on both warfare and agriculture.

According to history, the Aztecs were seen as violent barbarians, who generally lived in permanent conflict with the rest of the communities or tribes that were close to them. Furthermore, they strongly believed in human sacrifice as a way to calm the universe and serve as a tool for intimidation and dominance.

As the Spanish conquistadors marched toward Mexico and eager to assert control, they also sought to take the time to document the lives of those who were part of the Aztec culture. They did it that way because it was the most common way to convey their own story back then.

What cannot be doubted is that these Spanish conquerors had to make a lot of efforts to try to know the stories and culture of the Aztecs and then transmit from generation to generation each of the traditions and rituals typical of this organization. It is also believed that these stories could have served in reverse as fuel for the destruction of the Aztecs at the hands of the Spanish.

One of the many known Otomi legends is about the Legend of the Tlatoani Mocuitlach Nenequi, which was documented by Fray Alonso de Grijalva, who was one of the characters that accompanied Hernán Cortés during the historic Spanish expedition to Mexico. in the 1519s.

The legend was related by Gerónimo de Aguilar, who was a priest born in Spain and who was also taken to jail by a local Mayan tribe after having come out alive from a shipwreck several years ago. The truth is that this legend is considered by many to be one of the oldest within the Aztec culture, as well as one of the most popular.

The legend of the Tlatoani Mocuitlach Nenequi tells the story of a mysterious subject who was known only as Cuetlachtli, which in its popular translation refers to the word "Wolf". History says that this subject appeared on one occasion in the northeastern city of El Tajín.

As soon as he arrived in the city, he proclaimed himself the new king. Those who were not in favor of his position were in the power to step forward and challenge this man for taking the power to lead the people. The Mylonitic King of El Tajín, the third son of Mixcóatl and leader of the cult of Quetzalcóatl, came to light.

Legend has it that this Mylonitic King proceeded to call the "feathered serpent" in order to attack that mysterious subject, however Cuetlachtli changed his physical appearance and became a wolf and a man at the same time. In this new guise he proceeded to assassinate King Milonitica and claimed the throne.

It was in this way that the government of Cuetlachtli, the Tlatoani Mocuitlachnehnequi, began. It was believed that this mysterious character was native to the north of Aztlán, the ancestral home of the Nahuas. He was many centuries old, and it was also said that he was born on a huge mound.

Cuetlachtli's ancestors were mostly hunters, who also had the power to transform into wolves when the sun went down. These mysterious subjects had special powers and very different from all those seen before. His followers received his blood to make them walk like wolves. It was an honor given to those who could prove their bravery.

The legend narrates that the government of Tlatoani Mocuitlach Nenequi extended for many years. Throughout that time, many enemies came to light, especially in nearby towns. If there was something that characterized the army of Tlatoani Mocuitlach Nenequi, it was how little fear they had to fight.

This tribe proceeded to enter in a violent and savage way in the main neighboring cities. They did it like wolves and at once they attacked people while they were sleeping until they were killed. The members of this tribe were not in search of power, the only thing they were looking for was blood to feed on. They consumed the blood of all their victims until they were completely sated.

Several years passed, just when the Tlatoani Mocuitlachnehnequi were already exercising absolute power in the north, when surprisingly many members of his own Otomi (warrior class) rebelled against him with the intention of removing him from power. With the support of a shaman, the Otomi transformed into Jaguars and Coyotes.

For his part, Cuetlachtli and his allied forces were transformed into wolves and a fierce confrontation between both forces was unleashed in this way. Under the cover of night, the warring parties fell by the hundreds until there was none. Among the victims of that confrontation, Cuetlachtli did not figure, since he had disappeared, returning to the north, beyond the white land, which he will never see again.

Although it is true that too many years have passed since that confrontation began, the inhabitants of El Tajín, as well as other nearby towns, are still waiting for his return. Many prophecies have been announced around the return of Cuetlachtli.

One such prophecy says that when the mountains turn red with blood, then that will be the moment when Cuetlachtli returns. Those in danger will hear the wolf's cry as the brightest moon rumbles across the vastness of the sky.

According to many historians, this widely powerful and representative legend could have had a clear purpose and it was to intimidate and scare travelers who set foot on Central American soil, including the Spanish conquerors themselves as they tried to advance throughout Mexico.

"The simple fact that the Nahuatl translation of the words Tlatoani Mocuitlachnehnequ literally means "Our ruler resembles a wolf," may have given God-fearing warriors additional motive to kill people they saw as heathen heathens worshiping animals on the all mighty".

By the 1521s, Cortés had already conquered the Aztecs and the once mighty civilization would now be ravaged by death and disease. It is worth mentioning that the Spanish version of Tlatoani Mocuitlach Nenequi is so far the only known written version of the story.

For this reason, historians have agreed that it is a religious mythology of a simple society, however as this story is examined more closely, many mysterious elements appear that could raise the veracity of the legend.

There are those who say that the legend of Tlatoani Mocuitlach Nenequi could have been a simple horror story created to frighten the Spanish conquerors, however there are many clues and postscripts to the story that go far beyond a fiery tale of the bonfire of 1519.

It is also important to remember that in this type of culture, especially among the Aztecs and Mayans, there was a tradition within their mythologies of representing mortal men transformed into different animals. Now, the wolf has never been a strong symbol in any Mesoamerican culture, so why it appears in this story makes it difficult to understand.

What generates even more curiosity is that the legend of the werewolf is more linked to European culture than to Mesoamerican culture, which has led many historians to speculate that the original story has been modified after translation to fit more. to the Eastern tradition.

“A more interesting observation about this story is the correlation between Cuetlachtli, its origin and subsequent retreat to “Northern” lands. Archaeologists have long believed that Aztlán, which is mentioned in history by name, may have been located in what is now the Americas.”

The presumed birthplace linked to a "mound" brings to mind many archaeological sites in the United States, for example Bynum Mound in Mississippi, Etowah Mounds in Georgia, and Cahokia Mounds in Illinois, all of which predate the end of the Aztecs. empire.

It is true that the figure of the wolf was not so common in Aztec mythology, however, within the tradition of the Native Americans it did represent a lot. The figure of the "wolf" is almost always related to cultures of witchcraft and the myth of creation.

“Another note of curiosity, while Cuetlachtli is the derived form of the word “wolf” in the Nahuatl language, neither delineation appears anywhere in the more than 300 Native American languages that existed in North America. Oddly enough in a correspondence dated 1879, with Colonel Robert Quick of the 13th Cavalry of the United States Army.”

Colonel Quick was assigned the mission of capturing or assassinating a renegade Navajo nomad nicknamed Cuetlachtli. The story goes that all the members of the 13th Cavalry disappeared without a trace after having crossed the Medicine Bow Mountains while searching for the renegade.

Apart from the popular and traditional legend of Tlatoani Mocuitlach Nenequi, other stories that have been part of the Otomi culture are also known. We can mention legends such as "The Leg Cleaner", which has its origins in the south of Querétaro, where it analyzes the ideology of the indigenous community, which shares the Mexica concepts.

The truth is that the Quetzal people of Otomí have been characterized by turning each of their stories or myths into interesting stories, assuring the veracity of their stories, regardless of whether or not there is evidence that these events have actually occurred.

It is worth mentioning the case of the Mexquititla Foundation. This compilation includes some stories or myths related to the world, the creation of the sun and the moon, legends of ancient peoples, the approach of men with corn, women and snakes. Other legends belong to the Catholic worldview that narrates how Christ battled against demons.

language and writing

Within this ethnic group there is its own way of communicating, either orally or in writing. It is the Otomí language, a group of closely related indigenous languages of Mexico. It is estimated that this language is spoken by more than 240 thousand people who live in the central region of the high plateau of Mexico.

The Otomi language is considered one of the most popular Mexican indigenous languages in history. Today this language is practiced by a considerable number of indigenous people known as Otomí. It is a Mesoamerican language and reflects many characteristic aspects of the Mesoamerican linguistic area.

According to Mexico's Linguistic Rights Law, the Otomi language is accepted as a national language, as is the case with sixty-two other indigenous languages and Spanish. It is considered one of the most widely spoken indigenous languages of the Aztec country, so much so that it occupies position number seven on the list of the most widely spoken languages of Mexico.

The Otomi language should be taken as the "Otomi language family", because there are countless variants. It is important to point out that the number of speakers of Otomi languages has been declining in recent times, mainly due to the phenomenon of migration to which this indigenous community has been subjected.

As a curious fact, it could be mentioned that there is currently no record of written media in Otomí, that is, there are no newspapers or magazines in this language, except for sporadic communications and low-circulation books. However, the Mexican Ministry of Public Education, through the National Commission for Free Books, publishes several Otomi books for primary education.

As with the rest of the Oto-Manguean languages, Otomí is also considered a tonal language and most varieties distinguish between three tones. Names are marked for the holder only. The plural number is marked with a definite article and with a verbal suffix.

After the arrival of the conquering Europeans, Otomi became a written language when the friars spent much time teaching the Otomi about Latin grammar; the written language of the colonial period is often called Classic Otomí.

Proto-otomí period and later Pre-colonial period

The Oto-Pamean languages are thought to have split from the other Otomanguean languages around 3500 BC within the Ostomia branch. Proto-Otomí seems to have separated from Proto-Mazahua ca. 500 AD. Around the year 1000 AD, Proto-Otomí began to diversify into the modern Otomí varieties.

It is no secret to anyone that a large part of central Mexico was inhabited for several years by people who practiced the Oto-Pamean languages, at least that was the case before the arrival of Nahuatl speakers.

"Beyond this, the geographical distribution of the ancestral stages of most of the modern indigenous languages of Mexico, and their associations with various civilizations, remain indeterminate"

It has even been said that proto-otomí-mazahua is one of the languages practiced in Teotihuacán, the largest Mesoamerican ceremonial center of the Classic period, whose disappearance occurred around ca.600 AD It is also appropriate to clarify that the pre-Columbian Otomí people At that time, it did not have a widely developed writing system.

However, the great majority of Aztec writing was ideographic and could be understood in both Otomi and Nahuatl. The Otomi people had a tradition of frequently translating names of places or rulers into Otomi instead of using Nahuatl names.

Colonial period and classic Otomí

In the midst of the Spanish conquest that took place in central Mexico, the Otomi had a wider distribution than today. They had significant Otomi-speaking areas in some states like Jalisco and Michoacán. After the end of the Spanish conquest, the inhabitants of this ethnic group began to experience a period of geographical expansion.

The geographical expansion of the Otomi was due, among other things, to the fact that the Spanish conquerors used many warriors belonging to this indigenous ethnic group to carry out their conquest expeditions, especially in northern Mexico. After that period, the Otomi began to live in new areas, especially in Querétaro, where they founded the city of Querétaro.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GsU5GsQsnJc

They also settled in Guanajuato, a territory that years ago had been inhabited mostly by Chichimeca nomads. By this time some colonial historians, such as Bernardino de Sahagún, used mainly Nahua speakers as sources for their colonial histories.

Nahua speakers held a very negative view of the Otomi people, which lasted for virtually the entire colonial period. This trend of rejecting and devaluing the Otomi cultural identity compared to other indigenous communities gave way to the process of losing the language and miscegenation, due to the fact that a large part of the Otomi preferred to adopt the Spanish language and traditions.

Classic Otomí is the term used to refer to the Otomí that were spoken during the first centuries of colonial rule. It was a very interesting stage, where the language obtained Latin orthography and was documented by Spanish friars who began to learn more about this language, in order to use it as proselytism among the Otomi.

The reality is that the classic Otomi text is quite complex to understand, mainly because the friars and monks of the Spanish mendicant orders, such as the Franciscans, wrote Otomi grammars, the oldest of which is the Art of the Otomi language of Fray Pedro de Cárceres, written perhaps as early as 1580, but not published until 1907.

In the year 1605, another character in history, such as Alonso de Urbano, dared to create a trilingual Spanish-Nahuatl-Otomi dictionary, in which a small set of grammatical notes about Otomi can be seen. It is also known that the Nahuatl grammarian, Horacio Carochi, wrote an Otomi grammar, although there is no record of this to support the text.

During the second half of the XNUMXth century, a prominent Jesuit priest, whose name has not been revealed, wrote the Luces del Otomí grammar (which is not, strictly speaking, a grammar but a report on research on Otomí). For his part, Neve y Molina produced a dictionary and a grammar.

History tells us that during the colonial period, a large number of Otomis began to put their knowledge of their own language into practice, and it was even during this period that they were taught to read and write their language. For this reason, there is a significant number of documents made in Otomi, both secular and religious, the most popular being the Codices of Huichapan and Jilotepec.

During the late colonial period and after independence, indigenous groups no longer had a separate status. It was from then on that Otomi lost its status as a language of education, putting an end to the period of classical Otomi as a literary language.

All this reality leads to a stage of decline in the number of speakers of indigenous languages as indigenous groups throughout Mexico adopted the Spanish language as their main way of communicating. A hispanicization policy began to be implemented among them, which caused a rapid decrease in speakers of all indigenous languages, including Otomi, at the beginning of the XNUMXth century.

It is also worth remembering that during the 1990s, the central government authorities in Mexico decided to carry out a reversal of policies directed towards the rights of indigenous communities, including their languages.

In this way, important government institutions arose that had the main objective of promoting and protecting indigenous communities and languages. Among them we can name the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples and the National Institute of Indigenous Languages.

Culture and customs

If there is something worth highlighting about this indigenous community such as the Otomíes, it is their culture and each of the customs they carry out. Let's talk first about your music and dance. The dances are organizations where multiple social bonds intervene and are of great importance within the Otomi peoples.

Currently we have dances of colonial origin. Among them we can name the Apaches, arches, cowboys, muleteers, blacks and shepherdesses. In general, these dances are organized as part of the offerings offered by the inhabitants of the Otomi villages to their saints on the day of the festival.

It is worth saying that these dances are not only performed during the patron saint festival, but many of these traditional dances also take place during the Santa Cruz festival, which is when the rain petition rituals are carried out. They also usually dance at other common festivities such as baptisms or weddings.

Within the culture and customs of the Otomi peoples, it is worth mentioning the typical craft activity of these indigenous communities. The Otomí people are mainly characterized by making different handicrafts, among which we can name the production of wool rugs, molcajetes and stone metates.

They also have the custom of making palm hats, lite chairs, maguey fiber ayates, textiles made of waist cloth, among other activities. They also often use the reed to make pots, baskets, dove-shaped rattles and pitchers for pulque.

As part of their customs in terms of economy, it is important to mention that for the Otomi the most important traditional activity for them is agriculture. They generally specialize in the production of corn for self-consumption, but they also produce other items such as beans, chili, wheat, oats, barley, potatoes, squash and chickpeas.

Traditional holidays

In the Otomi towns there are many traditional festivals of great importance, however one of the most popular and well-known is the celebration of the Day of the Dead, which takes place every year on November 1. During this party it is customary to carry out different activities.

Possibly for many it is curious to celebrate the day of the dead, however for a good part of Mexicans, especially for indigenous communities, these types of celebrations have a special meaning. For them death and festivities are closely related.

This belief comes from the ancient indigenous peoples who inhabited Mexico, including the Otomi people, who believed that the souls of the dead returned every year to visit and earn a living: eat, drink and have a good time, just as they did when they were alive.

The festivity changed after the arrival of the Spanish in the fifteenth century. Now they continue to celebrate the day of the dead, but in the case of the souls of deceased children, they are remembered a day earlier, that is, on All Saints' Day. To remember their memories they do it with toys and colored balloons that adorn their graves.

During the day of the dead, adults who have died are also honored, but with displays of the deceased's favorite foods and beverages, as well as ornamental and personal objects. In the tombs it is customary to place flowers, especially cempasúchil and candles, which light the path of the spirits towards their relatives' houses.

Religion

The Otomi have their own religious beliefs, which are a mixture of Catholic and pre-Hispanic elements. Among their religious beliefs is the cult of the dead, the belief in some diseases, dreams and anecdotes that prevail in Otomi life. The vast majority of the Otomi identify with the Catholic religion and have the custom of paying veneration to many Christian images.

In recent years, the presence of Protestant religious groups within the Otomi towns has also grown surprisingly. They have a tradition of worshiping patron saints in regional temples. The religious beliefs of the Otomi are divided into large groups or philosophies.

- mesoamerican indian

- Catholic

- evangelical protestant

Otomi gods

One of the religious traditions that characterize the Otomi was precisely the worship of different deities, mostly related to essential aspects of nature, such as the Sun, the Moon, the Earth, the Wind, the Fire, the Water, among others. . Among their deities, two key characters also stood out: "Old Mother" and "Old Father".

In the metzca religion, it is worth making special mention of the cult that the Otomi performed towards the moon, however one of the most influential and significant Otomi gods was Otontecutli, considered the first leader of the Otomi, who also received worship from the mexica

Another of the main Otomi deities of Jilotepec was the god of the wind whom they called Edahi, equivalent to the Mexica Ehécatl. For his part, Fray Esteban García was sure that the Otomi of Tutotepec had the tradition of worshiping the air, personified in the wind god Edahi.

Besides, they had the custom of worshiping Muye, described as the lord of the rain, equivalent to the Mexica Tlaloc. Among the Otomi, there were the minor gods Ahuaque and Tlaloque who invoked the rain conjurers. The Otomi god of battles was called Ayonat Zyhtama-yo, while the Otomi of Tutotepec worshiped a god of the mountains called Ochadapo.

Most of the inhabitants of the Otomi villages have a tradition of firmly believing in witchcraft. They say that witchcraft is possible, plus they believe that evil airs have the power to cause illness. The Sierra Otomí use the term nagual to refer to superhuman vampires and the spirits of sorcerers' pets.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bAZxpetmvTg

The Otomi maintain the belief that lords of evil, such as Rainbow, Santa Catarina and the Queen of the Earth, have the power to cause harm to humans. It is also appropriate to mention that the people of Sierra Otomí, who live near the cities that have priests, mostly subscribe to Catholic doctrine.

A good part of the Otomi populations have been notably influenced by some religious currents, for example the Protestant gospel, a doctrine that is characterized, among other things, by rejecting the rest of the beliefs and providing an ideology to reject the cargo service.

religious practitioners

Within the Otomi peoples you can find many manifestations of a religious nature, for example the shamans. These people are described as religious specialists who face personal and family problems with other beings, whether superhuman, human, plant and animal.

Otomi shamans specialize in offering personal consultations and cures, in addition to intervening in different public ceremonies for pagan deities. For this reason, shamans also have priestly functions, although it is important to clarify that they are not organized in a bureaucratic hierarchy.

You might also be interested in the following articles: