For much of Antiquity, Persian culture continually mixed with that of its neighbors, primarily Mesopotamia, and influenced and was influenced by Sumerian and Greek art, as well as Chinese art via the "Silk Road" . In this opportunity, we bring you all the information you want to know about the persian art and more.

Persian art

Persian art in ancient times reflected their penchant for depicting the reality of their lives and history clearly; uncomplicated in the messages that the works of art were intended to convey. In Greater Iran that corresponds to the current states of:

- Iran

- Afghanistan

- Tajikistan

- Azerbaiyán

- Uzbekistan

As well as other nearby territories, they gave birth to one of the most valuable artistic legacies in the world, Persian art; where several disciplines were developed such as:

- Architecture

- Painting

- Fabrics

- Ceramics

- Calligraphy

- Metallurgy

- Masonry

- Music

With highly advanced techniques and imaginative artistic expressions that little by little we will get to know in the development of this article. Persian art was a reflection of their everyday problems and was represented in every dramatic and poetic medium they could use. Not only architecture, ceramics, painting, goldsmithing, sculpture or silverware extend this means of expression to poems, historical narratives and fantastic stories.

Additionally, it can be emphasized that the ancient Persians attributed great importance to the decorative aspect of their art, so it is essential to know each aspect of their history and their own characteristics to know exactly why their art originated and also how that they did it.

It is essential to highlight that the Persians exhibited their desires and aspirations as well as their particular way of seeing life with security, self-confidence and great inner power through the abundant symbolism and decorative style of their works.

History of the manifestation of Persian art

History is obviously a very powerful factor not only in shaping the cultural identity of a region, but also in giving it color and local identification. In addition, history contributes to being able to define the dominant cultural characteristics of the peoples of each region and for moments their artistic tendencies.

This statement in Persian art is very important to take into consideration, since in each period of this imaginative culture the artistic expression of the people was very aware of their social, political and economic environment.

Prehistory

The long prehistoric period in Iran is known mainly from the excavation works carried out in some important places, which led to a chronology of different periods, each characterized by the development of certain types of ceramics, artifacts and architecture. Pottery is one of the oldest Persian art forms, and examples have been discovered from tombs (Tappeh) dating back to the XNUMXth millennium BC.

For these times, the "animal style" with decorative animal motifs is very strong in Persian culture. It first appears on pottery and reappears much later in Luristan bronzes and again in Scythian art. This period is detailed below:

Neolithic

The inhabitants of the Iranian plateau lived in the mountains that surrounded it, as the central depression, now a desert was full of water at that time. Once the water receded, man descended into the fertile valleys and established settlements. Tappeh Sialk, near Kashan, was the first site to reveal Neolithic art.

During this period, the crude tools of the potter resulted in crude pottery and these large, irregularly shaped bowls were drawn with horizontal and vertical lines mimicking basket work. Over the years, the potter's tools improved and cups appeared, red in color, on which a series of birds, boars and ibexes (wild mountain goats) were drawn with simple black lines.

The high point in the development of prehistoric Iranian painted pottery occurred around the fourth millennium BC. Several examples have survived, such as the Painted Beaker from Susa c. 5000-4000 BC which is on display today in the Louvre, Paris. The patterns on this beaker are highly stylized.

The body of the mountain goat is reduced to two triangles and has become a mere appendage to the huge horns, the dogs racing on the mountain goat are little more than horizontal stripes while the waders that circle the mouth of the vase are They resemble musical notes.

Elamite

In the Bronze Age, although cultural centers certainly existed in various parts of Persia (for example, Astrabad and Tappeh Hissar near Damghan in the northeast), the kingdom of Elam in the southwest was the most important. Metalwork and the Persian art of glazing bricks particularly flourished in Elam, and from the inscribed tablets we can infer that there was a large industry in weaving, tapestry, and embroidery.

Elamite metalworking was particularly successful. These include, for example, a life-size bronze statue of Napirisha, wife of the 19th-century BC ruler Untash-Napirisha, and the Paleo-Elamite silver vase from Marv-Dasht, near Persepolis. This piece is XNUMX cm high and dates from the middle of the XNUMXrd millennium BC.

Adorned with the standing figure of a woman, dressed in a long sheepskin robe carrying a pair of castanets-like instruments, possibly summoning worshipers to her cylindrical cup. This woman's sheepskin robe resembles the Mesopotamian style.

Other Persian art objects found beneath the Inshushinak Temple, built by the same ruler, include a pendant with an Elamite inscription. The text records that the king of the twelfth century a. Shilhak-Inshushinak had the stone engraved for his daughter Bar-Uli, and the accompanying scene shows how it is presented to her.

Mesopotamia played an important role in Persian Elamite art; however, Elam still maintained its independence, especially in the mountainous areas, where Persian art can differ markedly from that of Mesopotamia.

Luristan

The Persian art of Luristan in western Iran mainly covers the period between the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries BC. C. and has become famous for its engraved bronze artifacts and castings of horse ornaments, weapons and banners. The most common Luristan bronzes are probably horse ornaments and harness ornaments.

The cheek pieces are usually very elaborate, sometimes in the form of ordinary animals such as horses or goats, but also in the form of imaginary beasts such as winged bulls with a human face. The head of a lion apparently became the most desired decoration on axes. To have the sword come out of the open jaws of a lion was to endow the weapon with the strength of the mightiest of beasts.

Many of the banners show the so-called "master of the animals", a human-like figure with the head of Janus, in the center fighting two beasts. The role of these standards is unknown; however, they may have been used as domestic shrines.

The Persian art of Luristan does not display the glorification of heroism and brutality of man, but revels in imaginary stylized monsters in which the call of this ancient Asian civilization is felt.

The Luristan bronzes are believed to have been made by the Medes, an Indo-European people who, in close association with the Persians, began to infiltrate Persia around this period. However, this has never been proven, and others believe they are connected to the Kassite civilization, the Cimmerians, or the Hurrians.

Antiquity

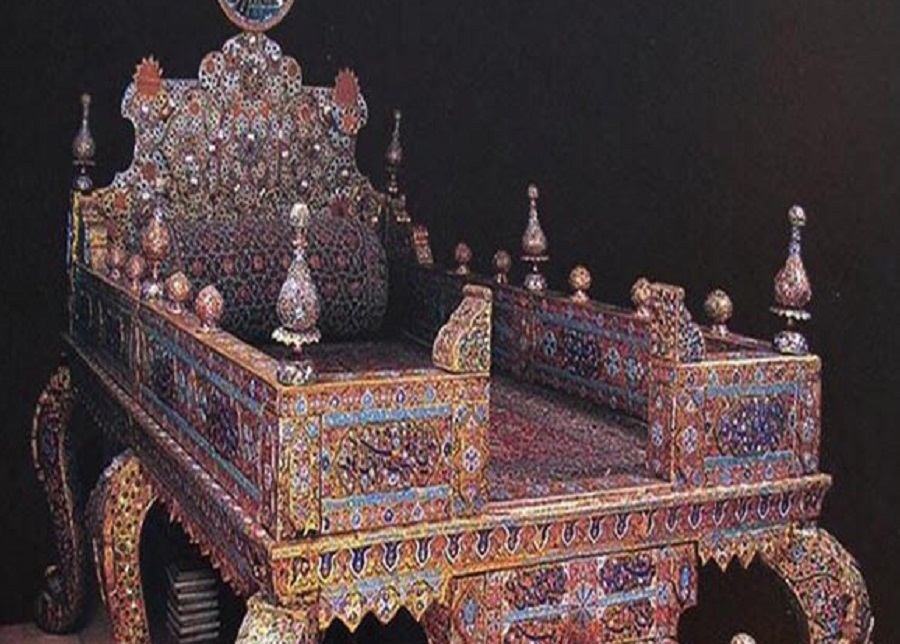

During the Achaemenian and Sassanian periods, the manifestation of prey art through goldsmithing continued its decorative development. Some of the best examples of metal objects are the gilt silver cups and plates decorated with royal hunting scenes from the Sassanid dynasty. Below are the salient features of each society within this time period:

the achaemenids

It can be said that the Achaemenid period began in 549 BC. C. when Cyrus the Great deposed the Medo monarch Astyages. Cyrus (559-530 BC), the initial great Persian monarch, created an empire that stretched from Anatolia to the Persian Gulf incorporating the ancient kingdoms of Assyria and Babylon; and Darius the Great (522-486 BC), who succeeded him after various disturbances, further expanded the boundaries of the empire.

Fragmentary remains of Cyrus's palace at Pasargadae in Fars indicate that Cyrus favored a monumental style of construction. He incorporated decoration based partly on Urartian, partly on older Assyrian and Babylonian art, as he wanted his empire to appear to be the rightful heir to Urartu, Assur and Babylon.

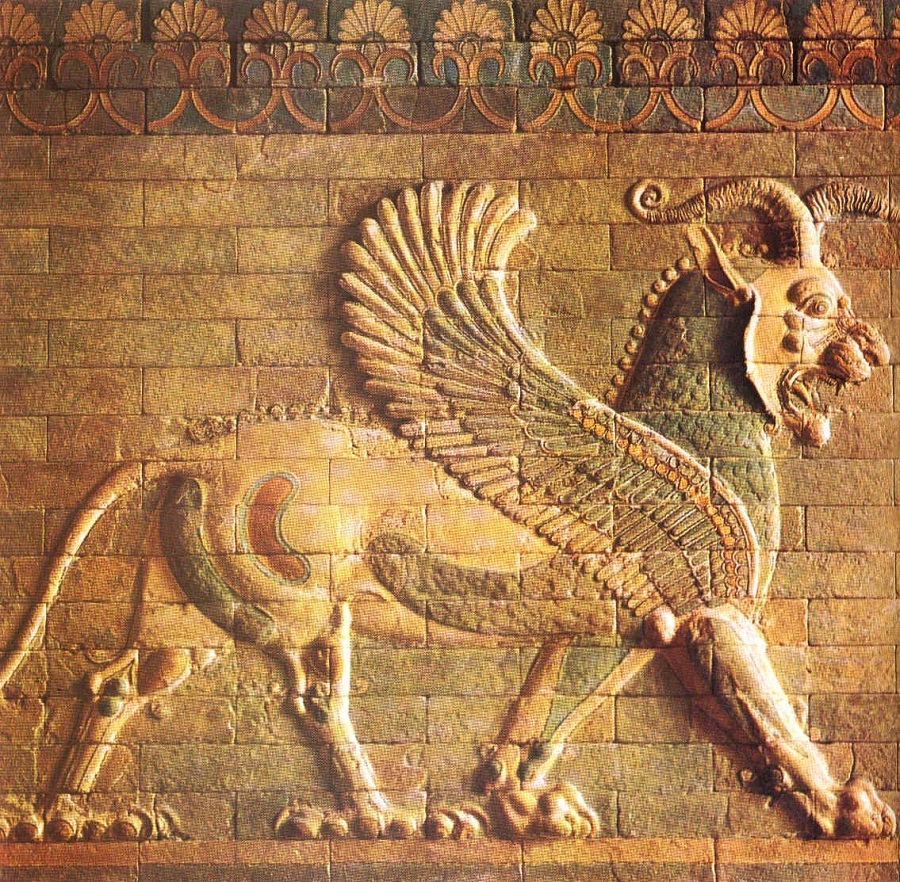

Pasargadae covered an area nearly 1,5 miles long and included palaces, a temple, and the tomb of the king of kings. Huge winged bulls, no longer extant, flanked the entrance to the gatehouse, but a stone relief on one of the gates still survives.

It is adorned with a bas-relief depicting a four-winged guardian spirit on a long Elamite-type garment, whose head is crowned by a complicated headdress of Egyptian origin. At the beginning of the XNUMXth century an inscription on the figure could still be seen and deciphered:

"I, Cyrus, king, the Achaemenid (have done this)".

The central hall of one of the palaces possessed bas-reliefs showing the king continuing from a pastoral bearer. In this depiction for the first time in Iranian sculpture, pleated garments emerge, in contrast to the plain robe of the four-winged guardian spirit, made according to the traditions of ancient Eastern art, which did not allow the slightest movement or life.

Achaemenid Persian art here marks the first step in the exploration of a means of expression that was to be developed by the Persepolis artists.

The rock-cut tombs at Pasargadae, Naqsh-e Rustam and other places are a valuable source of information on the architectural modes used in the Achaemenid period. The presence of Ionic capitals in one of the earliest of these graves suggests the serious possibility that this significant architectural mode was introduced to Ionian Greece from Persia, contrary to what is commonly supposed.

Under Darius, the Achaemenid Empire encompassed Egypt and Libya in the west and stretched to the Indus River in the east. During his rule, Pasargadae was relegated to a secondary role and the new ruler quickly began building other palaces, first at Susa and then at Persepolis.

Susa was the most important administrative center of the Empire of Darius, its geographical location halfway between Babylon and Pasargadae was very favorable. The structure of the palace that was built at Susa was based on a Babylonian principle, with three large inner courts around which were the reception and living rooms. In the courtyard of the palace, polychrome glazed brick panels decorated the walls.

These included a pair of winged lions with a human head under a winged disk, and so-called "Immortals". The craftsmen who made and laid these bricks came from Babylon, where there was a tradition of this type of architectural decoration.

Although Darius built several buildings at Susa, he is best known for his work at Persepolis (the Persepolis palace built by Darius and completed by Xerxes), 30 km southwest of Pasargadae. The decoration includes the use of carved wall slabs depicting the endless processions of courtiers, guards, and tributary nations from all parts of the Persian Empire.

Sculptors working in teams carved these reliefs, and each team signed their work with a distinctive mason's mark. These reliefs are executed in a dry and almost coldly formal, yet clean and elegant, style which henceforth was characteristic of Achaemenid Persian art and contrasts with the movement and enthusiasm of Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian art.

This Persian art was supposed to capture the viewer with its symbolism and convey a sense of grandeur; Therefore, artistic values were relegated to the background.

The king is the dominant figure in the Persepolis sculpture, and it seems that the whole purpose of the decorative scheme was to glorify the king, his majesty and his power. So, we can also see that the Persepolis sculptures differ from the Assyrian reliefs, which are essentially narrative and aim to illustrate the achievements of the king.

However, the similarities are such that it is obvious that much of the inspiration for this type of relief must have come from Assyria. Greek, Egyptian, Urartian, Babylonian, Elamite, and Scythian influences can also be seen in Achaemenid art. This is perhaps not surprising, in view of the wide range of people employed in the construction of Persepolis.

Achaemenid Persian art, however, was also capable of influencing that of others, and its imprint is most notable in the early art of India, with which it probably came into contact via Bactria. The realism of Persian Achaemenid art manifests its power in the representation of animals, as can be seen in the many reliefs at Persepolis.

Carved in stone or cast in bronze, the animals served as guardians of entrances or, more often as supports for vases, in which they were grouped in threes, their union a revival of the ancient traditions of tripods with legs ending in a hoof or paw of a lion. Achaemenian artists were worthy descendants of the animal sculptors of Luristan.

Silverwork, glazing, goldsmithing, bronze casting, and inlay work are well represented in Achaemenid Persian art. The Oxus Treasure, a collection of 170 gold and silver pieces found by the Oxus River dating from the XNUMXth to XNUMXth century BC Among the best-known pieces is a pair of gold bracelets with terminals in the shape of horned griffins, originally embedded glass and colored stones.

The Persian art of the Achaemenids is a logical continuation of what preceded it, culminating in the superb technical skill and unprecedented splendor so evident at Persepolis. The Persian art of the Achaemenians is deeply rooted in the time when the first Iranians arrived on the plateau, and its wealth has accumulated over the centuries to finally constitute the splendid achievement of Iranian art today.

the hellenistic period

After Alexander conquered the Persian Empire (331 BC), Persian art underwent a revolution. Greeks and Iranians lived together in the same city, where intermarriage became common. Thus, two profoundly different concepts of life and beauty were pitted against each other.

On the one hand, all the interest was focused on modeling the plasticity of the body and its gestures; while on the other there was nothing but dryness and severity, a linear vision, rigidity and frontality. Greco-Iranian art was the logical product of this encounter.

The victors, represented by the Seleucid dynasty of Macedonian origin, replaced the ancient Eastern art with Hellenistic forms in which space and perspective, gestures, curtains and other devices were used to suggest movement or various emotions, however, still Some oriental features remained.

Parthians

In 250 BC C., a new Iranian people the Parthians, proclaimed their independence from the Seleucids and reestablished an Eastern Empire that extended to the Euphrates. The reconquest of the country by the Parthians brought a slow return to Iranian traditionalism. His technique marked the disappearance of the plastic form.

The rigid, often highly jeweled figures, dressed in Iranian costumes with their drapery emphasized in a mechanical and monotonous manner, were now systematically shown facing forward, that is, directly at the viewer.

This was a device used in ancient Mesopotamian art only for figures of exceptional importance. However, the Parthians made it the rule for most figures, and from them it passed into Byzantine art. A beautiful bronze statue (of Shami) and some reliefs (at Tang-i-Sarwak and Bisutun) highlight these features.

During the Parthian period, the iwan became a widespread architectural form. This was a large hall, open on one side with a high vaulted ceiling. Particularly good examples have been found at Ashur and Hatra. Fast-setting gypsum mortar was used in the construction of these grandiose rooms.

Perhaps allied with the increasing use of plaster mortar was the development of plaster stucco decoration. Iran was not familiar with stucco decoration before the Parthians, among which it was fashionable for interior decoration along with wall painting. The Dura-Europos mural, on the Euphrates, depicts Mithras hunting a variety of animals.

Many examples of Parthian 'clinky' pottery, a hard red pottery that makes a clinking noise when struck, can be found in the Zagros area of western Iran. It is also common to find glazed pottery with a pleasant bluish or greenish lead glaze, painted on Hellenistic-inspired forms.

During this period ornate jewelry with large inlays of stones or glass gems appeared. Unfortunately, virtually nothing that the Parthians may have written has survived, save a few inscriptions on coins and accounts by Greek and Latin authors; however, these accounts were far from objective.

Parthian coins are useful in establishing the succession of kings, they referred to themselves on these coins as "Hellenophiles", but this was only true because they were anti-Roman. The Parthian period was the beginning of a renewal in the Iranian national spirit. This Persian art constitutes an important springboard of transition; which led on the one hand to the art of Byzantium, and on the other to that of the Sassanids and India.

the sassanids

In many ways, the Sassanian period (224-633 AD) witnessed the greatest achievement of Persian civilization and was the last great Iranian empire before the Muslim conquest. The Sassanid dynasty, like the Achaemenid, originated in the province of Fars. They saw themselves as successors to the Achaemenians, after the Hellenistic and Parthian interlude, and perceived it as their role in restoring the greatness of Iran.

At its height, the Sasanian Empire stretched from Syria to northwestern India; but his influence was felt far beyond these political borders. Sassanid motifs found their way into the art of Central Asia and China, the Byzantine Empire, and even Merovingian France.

In reviving the glories of the Achaemenid past, the Sassanids were not mere imitators. Persian art of this period reveals an amazing virility. In certain respects, it anticipates features developed later during the Islamic period. The conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great had inaugurated the spread of Hellenistic art in western Asia; but if the East accepted the outward form of this art, it never really assimilated its spirit.

During Parthian times, Hellenistic art was already being lightly elucidated by the peoples of the Near East, and by Sassanian times there was a continual process of resistance to it. Sassanian Persian art revived modes and practices native to Persia; and in the Islamic stage they reached the shores of the Mediterranean.

The magnificence in which the Sassanid monarchs subsisted is perfectly represented by the palaces that remained standing, as well as those of Firuzabad and Bishapur in Fars, and the metropolis of Ctesiphon in Mesopotamia. In addition to local habits, Parthian architecture must have been the guarantor of various Sassanid architectural particularities.

All are characterized by barrel-vaulted iwans introduced in the Parthian period, but now attained massive proportions, particularly at Ctesiphon. The arch of the great vaulted hall of Ctesiphon attributed to the reign of Shapur I (AD 241-272) has a span of over 80 feet and reaches a height of 118 feet from the ground.

This lavish structure magnetized architects in later times and has been admired as one of the most significant pieces of Persian architecture. Several of the palaces have inside an audience hall that is located, as in Firuzabad, in a chamber perfected by a dome.

The Persians solved the problem of erecting a round dome on a square work by the squinch. Which is nothing more than an arch raised along each corner of the square, thus transforming it into an octagon on which it is easy to place the dome. The dome chamber of the palace at Firuzabad is the earliest surviving example of the use of the squinch, and there is therefore good reason to regard Persia as its place of invention.

Among the peculiarities of Sassanian architecture, its emblem use of space can be mentioned. The Sassanian architect imagined his construction in conceptions of volumes and surfaces; hence the use of solid brick walls adorned with modeled or worked stucco.

Stucco wall decorations appear at Bishapur, but better examples are preserved from Chal Tarkhan near Rayy (late Sassanid or early Islamic in date), and from Ctesiphon and Kish in Mesopotamia. The panels show animal figures in circles, human busts, and geometric and floral motifs.

In Bishapur, some of the floors were ornamented with mosaics displaying fun facts as in a feast; Roman dominance here is clear, and the mosaics may have been installed by Roman prisoners. The buildings were also adorned with wall paintings; particularly good examples have been found at Kuh-i Khwaja in Sistan.

On the other hand, Sassanid sculpture offers an equally striking contrast to that of Greece and Rome. Currently, about thirty rock sculptures survive, most of them located in Fars. Like those of the Achaemenid period, they are carved in relief, often on remote and inaccessible rocks. Some are so deeply undermined that they are practically independent; others are little more than graffiti. Its purpose is the glorification of the monarch.

The first Sassanid rock carvings to be presented are those of Firuzabad, linked to the beginning of the reign of Ardashir I and still linked to the principles of Parthian Persian art. The relief itself is very minimal, the details are made by delicate cuts and the shapes are heavy and abundant, but not without a certain vigor.

One relief, carved into a rock face in the Tang-i-Ab Gorge near the Firuzabad Plain, consists of three separate dueling scenes that vividly express the Iranian concept of battle as a series of individual engagements.

Many represent the investiture of the king by the god "Ahura mazda" with the emblems of sovereignty; others the triumph of the king over his enemies. They may have been inspired by Roman triumphal works, but the manner of treatment and presentation is very different. Roman reliefs are pictorial records always with an attempt at realism.

Sasanian sculptures commemorate an event by symbolically representing the culminating incident: for example, in the Naksh-i-Rustam sculpture (XNUMXrd century), the Roman Emperor Valerian hands over his arms to the victor Shapur I. Divine and royal characters are represented on a scale greater than that of inferior people. The compositions are, as a rule, symmetrical.

Human figures tend to be stiff and heavy, and there is an awkwardness in the rendering of certain anatomical details such as the shoulders and torso. Relief sculpture reached its zenith under Bahram I (273-76), the son of Shapur I, who was responsible for a beautiful ceremonial scene at Bishapur, in which the forms have lost all rigidity and the workmanship is elaborate and vigorous.

If the entire collection of Sassanian rock carvings is considered, a certain stylistic rise and fall becomes apparent; Starting from the flat forms of the first reliefs founded on the Paratian tradition, Persian art became more sophisticated and, due to Western influence, more rounded forms that appeared during the period of Sapphire I.

Culminating in the dramatic ceremonial scene of Bahrain I at Bishapur, then regressing to hackneyed and uninspired forms under Narsah, and finally returning to the non-classical style evident in the reliefs of Khosroe II. There is no attempt to portray in Sassanian Persian art, neither in these sculptures nor in the actual figures depicted on metal vessels or their coins. Each emperor is simply distinguished by his own particular form of crown.

In the minor arts, sadly no painting has survived, and the Sassanid period is best represented by its metalwork. A large number of metal vessels have been attributed to this period; many of these have been found in southern Russia.

They come in a variety of shapes and reveal a high level of technical skill with decoration executed by hammering, tapping, engraving or casting. The subjects most frequently depicted on silver plates included royal hunts, ceremonial scenes, the enthroned king or banquets, dancers, and religious scenes.

Vessels were decorated with designs executed in various techniques; gilt, plated or etched packets and cloisonné enamel. Motifs include religious figures, hunting scenes in which the king takes center stage, and mythical animals such as the winged griffin. These same designs occur in Sassanian textiles. Silk weaving was introduced to Persia by the Sassanian kings and Persian silk weaving even found a market in Europe.

Few Sassanid textiles are known today, apart from small fragments from various European abbeys and cathedrals. Of the magnificent heavily embroidered royal fabrics, studded with pearls and precious stones, nothing has survived.

They are known only through various literary references and the ceremonial scene in the Taq-i-Bustan, in which Khosroe II is dressed in an imperial cloak resembling the one described in legend, woven of gold thread and studded with pearls and beads. rubies

The same goes for the famous garden rug, the "Spring of Khosroe". Made during the reign of Khosroe I (531 – 579), the carpet was 90 square feet. Whose description of Arab historians is as follows:

“The border was a magnificent flower bed of blue, red, white, yellow, and green stones; in the background the color of the earth was imitated with gold; crystal-clear stones gave the illusion of water; the plants were made of silk and the fruits were made of colored stones».

However, the Arabs cut this magnificent rug into many pieces, which were then sold separately. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Sassanid art is its ornament, which was destined to have a profound influence on Islamic art.

Designs tended to be symmetrical and much use was made of attached medallions. Animals and birds and even floral motifs were often presented heraldically, that is, in pairs, facing each other or back to back.

Some motifs, such as the Tree of Life, have an ancient history in the Near East; others, like the dragon and the winged horse, reveal Asian art's constant love affair with the mythical.

Sassanian Persian art spread over an immense territory stretching from the Far East to the shores of the Atlantic and played a fundamental role in the formation of medieval European and Asian art. Islamic art, however, was the true heir to Persian-Sassanid art, the concepts of which it was to assimilate and, at the same time, infuse it with fresh life and renewed vigor.

early islamic period

The Arab conquest in the XNUMXth century AD brought Persia into the Islamic community; however, it was in Persia that the new movement in Islamic art met its severest test. Contact with a people of high artistic achievement and ancestral culture made a deep impression on the Muslim conquerors.

When the Abbasids made Baghdad their capital (close to the ancient metropolis of the Sassanian rulers), a vast current of Persian influences came through. The caliphs accepted the ancient Persian culture; a policy was also followed at the courts of the relatively independent local principalities (Samanids, Buyids, etc.), which led to a conscious revival of Persian traditions in art and literature.

Wherever possible, new life was breathed into the cultural heritage of Persian art, and customs completely unrelated to Islam were maintained or re-introduced. Islamic art (paintings, metalwork, etc.) was heavily influenced by Sassanian methods, and Persian vaulting techniques were adopted in Islamic architecture.

Few secular buildings have survived from the early period, but judging from the remains, it is likely that they retained many features of Sassanian palaces, such as the 'vaulted audience hall' and 'plan arranged around a central courtyard'. The main change that this period brought to the development of art was to restrict the representation of realistic portraits or real-life representations of historical events.

"On the day of Resurrection, God will consider the image makers as the men most deserving of punishment"

Collection of sayings of the Prophet

Since Islam did not tolerate the three-dimensional representation of living creatures, Persian craftsmen developed and expanded their existing repertoire of ornamental forms, which they then cast in stone or stucco. These provided a common material on which artists in other media drew.

Many of the motifs date back to ancient Near Eastern civilizations: they include fabulous beasts such as the winged human-headed sphinx, griffins, phoenixes, wild beasts or birds hooked on their prey, and purely ornamental devices such as medallions, vines, floral motifs and the rosette.

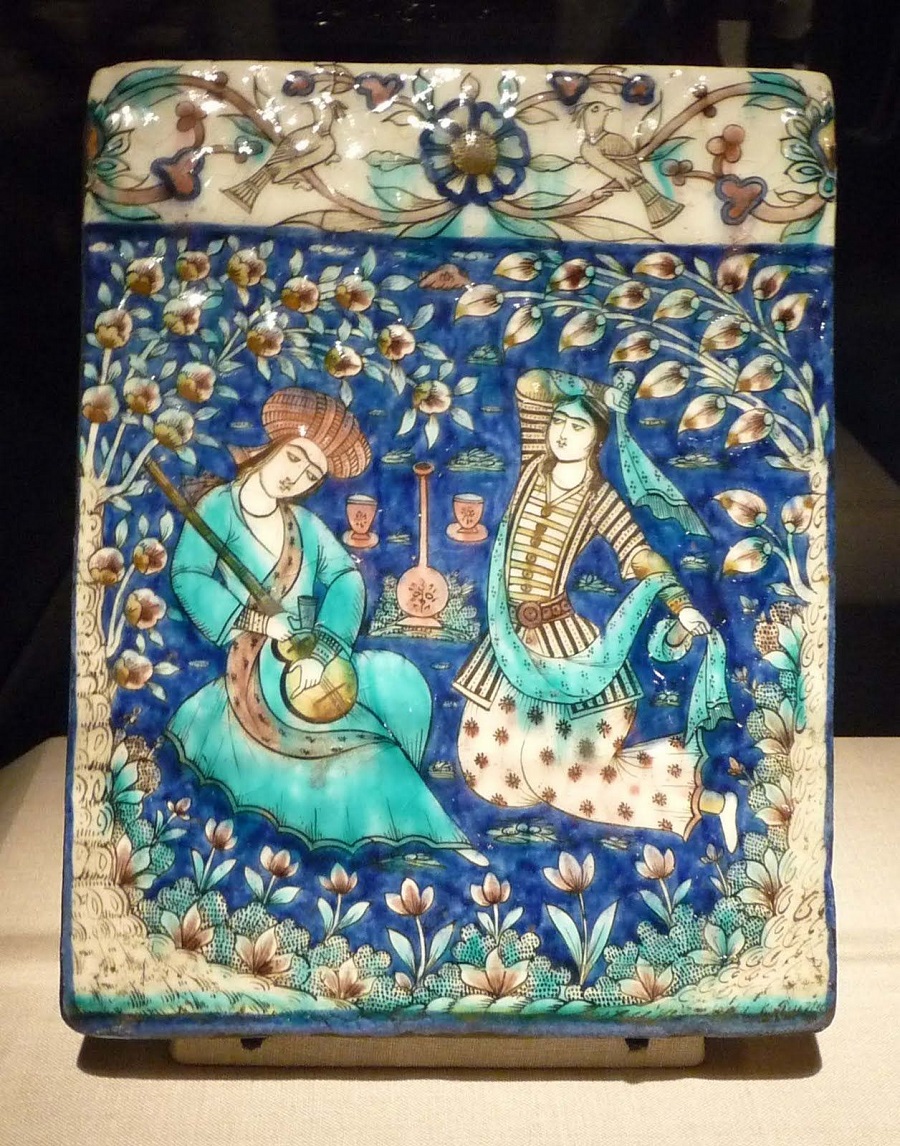

The more tolerant Muslim believers were less strict about the depiction of figurative art, and in bathhouses, hunting or love-scene paintings for the entertainment of patrons seldom aroused objections.

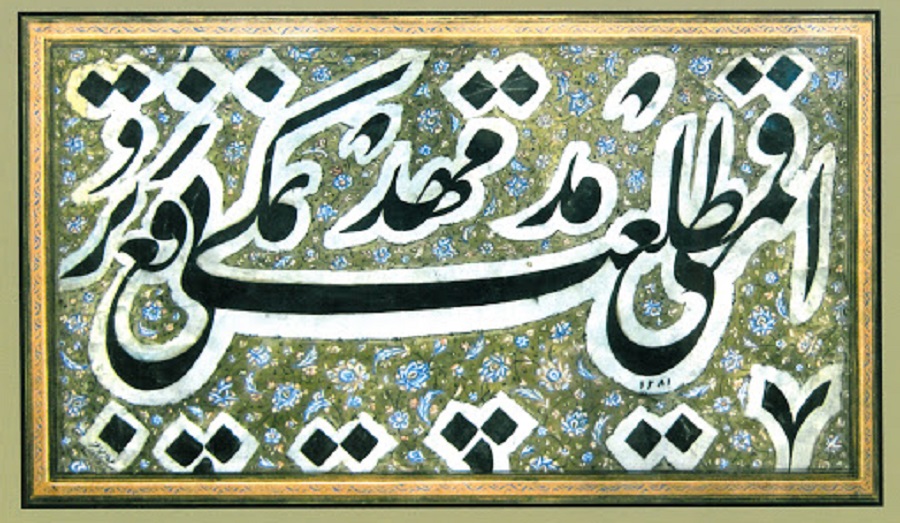

However, in religious establishments, only indistinct hints of human or animal forms were tolerated. The Persians quickly appreciated the decorative value of Arabic script and developed all varieties of floral and abstract ornaments. Persian adornment is generally distinguished from that of other Islamic countries.

Arabesque treatment tended to be freer in Persia than elsewhere, and usually, though not always, retained natural and recognizable plant forms. Palmettes, frets, guilloches, interlacing and elaborate geometric figures such as the polygonal star are also produced.

Calligraphy is the highest art form of Islamic civilization and like all art forms that came into contact with Iran, it was improved and developed by the Persians. Ta'liq, "hanging script" (and its derivative Nasta'liq) was formalized in the thirteenth century; although it had been around for centuries before this, and is claimed to be derived from the ancient pre-Islamic Sassanid script.

The written page was also enriched by the art of the "Illuminator" and in some manuscripts by that of the painter, who added small-scale illustrations. The tenacity of Persia's cultural tradition is such that, despite centuries of invasions and foreign rule by Arabs, Mongols, Turks, Afghans, etc. His Persian art reveals a continuous development, while preserving its own identity.

During Arab rule, the adherence of the local population to the Shia sect of Islam (which opposed rigid Orthodox observance) played a major role in their resistance to Arab ideas. By the time orthodoxy took hold, through the conquest of the Seljuks in the eleventh century, the Persian element had become so deeply entrenched that it could no longer be uprooted.

abadas period

Once the initial shock of the Arab invasion wore off, the Iranians went to work assimilating their victors. Artists and craftsmen made themselves available to the new rulers and the needs of the new religion, and Muslim buildings adopted the methods and materials of the Sassanid period.

The size of buildings and construction techniques in the Abbasid period show a revival of Mesopotamian architecture. The bricks were used for walls and pillars. These pillars then acted as freestanding supports for vaults that were repeatedly used throughout the Muslim world, due to the scarcity of roofing timber.

The wide variety of arches in Abbasid architecture leads one to believe that their various forms served ornamental purposes rather than structural requirements.

Of all the decorative arts, pottery made the most notable advances during the Abbasid period. In the XNUMXth century, new techniques were developed in which bold designs were painted with a strong cobalt blue pigment on a white background. Various shades of glitter were sometimes combined on a white background, including red, green, gold, or brown.

Towards the end of the XNUMXth century, animal and human silhouette designs became quite common, on a plain or densely covered background. Pottery from the late Abbasid period (XNUMXth to early XNUMXth centuries) includes:

- Carved or molded lamps, incense burners, floor tables and tiles with turquoise green enamel.

- Jars and bowls painted with floral motifs, gallons, animals or human figures, etc., under a green or transparent glaze.

- Jars, bowls, and tiles painted with a dark brown sheen over a light greenish glaze; glitter is sometimes combined with blue and green lines.

Early Abbasid-era paintings are known from fragments excavated at Samarra, outside western Iran (approximately 100 kilometers north of Baghdad, Iraq).

These wall paintings were found in the reception rooms of bourgeois houses and in the non-public parts of palaces, especially in the harem quarters, where no religious functions were held.

A favorite place of such decorations were the domes above square aisles. Much of the imagery has Hellenistic elements, as evidenced by the drinkers, dancers, and musicians, but the style is basically Sassanian in spirit and content. Many have been reconstructed using Sassanian monuments such as rock reliefs, seals, etc.

In eastern Iran, a painting of a woman's head (late XNUMXth or early XNUMXth century) found at Nishapur bears a strong resemblance to the art of Samarra; however, it is hardly affected by Hellenistic influences.

Pictorial Persian art (miniatures) in the final period before the destruction of the caliphate is found mainly in manuscripts illustrating scientific or literary works and was mostly restricted to Iraq.

the samanids

With the decline in power of the caliphs in the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries, the feudal lords gradually returned to power, establishing independent principalities in eastern Iran; one of the most important was ruled by the Samanids. The Samanid rulers were great patrons of Persian art and made Bukhara and Samarkand in Transoxiana famous cultural centers.

The most complete documentation of Samanid Persian art is found in its ceramics, and during the XNUMXth century, Transoxiana wares were very popular in the eastern provinces of Persia. The best known and most refined pottery of this type from Samarkand is the one with large inscriptions in Kufic (the earliest version of the Arabic script used in the Koran, named after the city of Kufa in Iraq) painted in black on a White background.

Figure decoration never appeared on these Transoxiana wares and motifs were often copied from textiles such as rosettes, roundels, and peacock tail "eyes". On the other hand, the Khorasan pottery of the Samanid period known mainly from material excavated at Nishapur, did not eliminate the human form, and there are examples of human figures against backgrounds rich in animals, flowers, and inscriptions.

Unfortunately, virtually nothing remains of Samanid paintings or miniatures apart from a few fragments of wall paintings found at Nishapur. One such fragment depicts a life-size image of a falconer on horseback, riding at a "flying gallop" in ways derived from the Sassanid tradition. The falconer dresses in the Iranian style with influences from the steppe, such as high boots.

As for textiles, what have survived are several examples of tiraz (strip of cloth used to decorate the sleeve) from Merv and Nishapur. Nothing remains of the vast output of the textile workshops of Transoxiana and Khorasan, except for the celebrated fragment of silk and cotton known as the "Shroud of St. Josse."

This piece is decorated with elephants facing each other highlighted by borders of kufic characters and rows of Bactrian camels. It is inscribed on Abu Mansur Bukhtegin, a high Samanid court official who was sentenced to death by Abd-al-Malik ibn-Nuh in 960. The cloth is almost certainly from the Khorasan workshop. Although the figures are quite rigid, the Sassanid models have been closely followed, both in overall composition and in individual motifs.

the seljuks

The Seljuk period in the history of art and architecture spans about two centuries from the Seljuk conquest in the second quarter of the XNUMXth century to the establishment of the Ilkan dynasty in the second quarter of the XNUMXth century. During this period, the center of power within the Islamic world shifted from the Arab territories to Anatolia and Iran, with the traditional centers now residing in the Seljuk capitals: Merv, Nishapur, Rayy, and Isfahan.

Despite the Turkish invaders, this era of Persian renaissance beginning with the publication of Firdawsi's "Shah-namah" constitutes a period of intensely creative artistic development for Persia. The sheer productivity of these centuries in the visual arts compared to the art of previous centuries represents a great leap forward.

The importance of Seljuk Persian art is that it established a dominant position in Iran and determined the future development of art in the Iranian world for centuries. The stylistic innovations introduced by the Iranian architects of this period had, in fact, great repercussions, from India to Asia Minor. However, there is a strong overlap between Seljuk art and the stylistic groupings of the Buyids, Ghaznavids etc.

In many cases, the artists of the Seljuk period consolidated, and sometimes refined, forms and ideas that had been known for a long time. It must be remembered that the picture is not as clear as it should be, with the massive scale of illegal excavations in Iran over the last hundred years.

The characteristic feature of the buildings of this period is the decorative use of unrendered bricks. The earlier use of stucco coatings on the exterior walls, as well as the interior (to disguise the inferiority of the building material), was discontinued, although it reappeared later.

With the establishment of the Seljuk Turks (1055-1256) a distinctive form of mosque was introduced. Its most striking feature is the vaulted niche or iwan which had figured prominently in Sassanid palaces and was known even in the Parthian period. In this so-called "cruciform" mosque plan, an iwan is inserted into each of the four surrounding court walls.

This plan was adopted for the reconstruction of the Great Mosque of Isfahan in 1121 and was widely used in Persia until recent times. A notable example is the Masjid-i-shah or Royal Mosque founded by Shah Abbas in Isfahan in 1612 and completed in 1630. Figure decoration appeared on Seljuk pottery from the mid-XNUMXth century onwards.

At first, the decoration was carved or molded, while the enamel was monochrome, although carved items of various colors were used in the lakabi (painting). Sometimes the decoration was applied to the pot, painted in black slip under a clear or colored glaze to create a silhouette effect.

Large birds, animals, and fabulous creatures make up most of the images, although human figures appear in silhouette. The figures of the silhouette are usually independent, although it is usual that the human and animal forms are always presented or superimposed on a background of foliage.

The last quarter of the XNUMXth century saw the creation of splendid and elaborate minai (glaze) pottery, made using a double-firing technique to set glaze over glaze. This type of pottery, which originated in Rayy, Kashan and perhaps Saveh, shows ornamental details similar to the brightly painted pottery of Kashan. Some compositions represent battle scenes or episodes taken from the Shah-namah.

The Seljuk miniatures of which few traces remain due to widespread destruction by the Mongol invasions, must also have been extremely ornate, like other forms of Persian art of the time, and certainly must have displayed similar characteristics to pottery painting.

The main center of book painting in the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries was Iraq, but this painting had a marked Iranian influence. Several good examples of Seljuk Qur'ans have survived, and they are noted for their magnificent title page painting, often strongly geometric in character, with Kufic script taking the lead.

During the Seljuk period, metalworking was particularly widespread with extremely high levels of manpower. Bronze was by far the most widely used metal during the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries (bronze being a later addition).

Artifacts were cast, engraved, sometimes inlaid with silver or copper or executed in fretwork, and in some cases even adorned with enamel decorations. In the twelfth century, the techniques of repoussé and engraving were added to those of inlaying bronze or brass with gold, silver, copper and niello.

A notable example is the bronze cube inlaid with silver and copper now kept in the Hermitage Museum in Leningrad. According to its inscription, it was made in Herat in 1163.

At that time a wide range of objects were produced such as perfume burners usually in the form of animals, mirrors, candle holders, etc. and it seems likely that some of the best craftsmen travel extensively to execute commissions with fine pieces shipped long distances.

The Seljuk period was undoubtedly one of the most intensely creative periods in the history of the Islamic world. It showed splendid achievements in all artistic fields, with subtle differences from region to region.

The Mongols and the Ilkhanate

The Mongol invasions in the 1220th century changed life in Iran radically and permanently. Genghis Khan's invasion in the 1258s destroyed lives and property in northeastern Iran on a massive scale. In XNUMX, Hulagu Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, completed the conquest of Iran and consolidated his control over Iraq, Iran, and much of Anatolia.

With his capital at Maragha in northwestern Iran, he founded the Ilkhanid kingdom, nominally subject to the Great Khan, Qubilai, ruler of China and Mongolia.

The Ilkan dynasty, which lasted from 1251 to 1335, represents in Persian art (paintings, pottery and goldsmithing) the period of greatest influence in the Far East. Later Ilkhanates attempted to repair some of the destruction caused by their devastating invasion in the early XNUMXth century, building new cities and employing native officials to administer the country.

Ilkania architecture was not a new style in its time, but continued Seljuk plans and techniques. Double-domed Seljuk architecture was very popular among the Ilkhanates and displays of decorative bricks, although not completely abandoned, gave way to an increasing use of glazed pottery.

In Iran, large interior and exterior surfaces were first covered with large faience mosaics (tile mosaic) of geometric, floral, and calligraphic motifs in the XNUMXth century. The technique was probably re-imported at this time from Asia Minor, where Persian artists had fled before the Mongol invasion. One of the earliest Iranian monuments with large areas of faience mosaics is the Oljeitu Mausoleum in Sultaniya.

As far as pottery is concerned, all activity at Rayy ceased after the Mongol destruction in 1220, but Kashan pottery immediately bounced back from its hardships in 1224.

The tiles were used extensively both in architectural decoration and in mihrab and in the Imamzada Yahya of Varamin, which has a mihrab dating from c. 1265, with the signature of the famous Kashan potter Ali ibn-Muhammad ibn Ali Tahir. These were called kashi after their production center in Kashan.

There are two types of pottery most associated with the Ilkhanates, one is "Sultanabad" (whose name was taken from where the first pieces were discovered in the Sultanabad region) and the other "Lajvardina" (a simple successor to the Minai technique). . Gold overpainting on a deep blue glaze makes Lajvardina tableware one of the most spectacular ever produced in Persia.

In contrast to this, the Sultanabad ware is heavily potted and makes frequent use of gray slip with thick outlines, while another type shows black paint under a turquoise glaze. The pattern is of indifferent quality, but the pottery as a whole is of special interest as a classic example of the way in which Chinese motifs invaded the Persian pottery tradition.

The metallurgy that had flourished in northeastern Persia, Khurassan, and Transoxiana, also suffered terribly from the Mongol invasion; however, it did not die out completely. After a gap in production of nearly a century, which may be closely paralleled in architecture and painting, the industry was revived. The key centers were in Central Asia, Azerbaijan (the main center of Mongol culture), and southern Iran.

The combination of Persian, Mesopotamian and Mamluk styles is characteristic of all Ilkhanate goldsmithing. Mesopotamian metal inlay seems to have been inspired by the techniques of Persian art, which he developed and perfected. Bronze was increasingly replaced by brass, with gold inlay replacing red copper.

There was also a tendency in Mesopotamian work to cover the entire surface in minute ornamental patterns, and human and animal figures were always well defined. However, Persian works showed a preference for an inlay and engraving technique that avoided rigid and precise contours. There was also a reluctance to cover the entire surface with decorations.

Towards the end of the XNUMXth century, the influence of the Far East becomes evident in both the Persian and Mesopotamian styles in the more naturalistic treatment of plant ornaments (including the lotus flower…) and the typically elongated human form.

the timurids

One hundred and fifty years after the Mongols first invaded Iran, the armies of Timur the Lame (Tamerlane, a conqueror only slightly less fearsome than his ancestor Genghis Khan) invaded Iran from the northeast. The artisans were spared the massacres and transported to their capital Samarkand, which they embellished with spectacular buildings, including now-defeated palaces with wall paintings depicting Timur's victories.

In the time of Shah Rukh and Oleg Begh, the Persian art of miniature reached such a degree of perfection that it served as a model for all later schools of painting in Persia. The most notable feature of the new Timurid style (although derived from the earlier Ilkan period) is a new conception of space.

In miniature painting, the horizon is placed high so that different planes are formed in which objects, figures, trees, flowers and architectural motifs are arranged almost in perspective. This allowed the artist to paint larger groups with greater variety and spacing, and without crowding. Everything is calculated, these are pictures that make high demands on the viewer and do not lightly reveal their secrets.

Two of the most influential schools were in Shiraz and Herat. So under the patronage of Sultan Ibrahim (1414-35), the Shiraz school, building on the earlier Timurid style, created a highly stylized way of painting in which bright and vigorous colors predominated. The compositions were simple and contained few figures.

The same city was later an important center for the Turkmen style dubbed after the ruling dynasty of western and southern Iran. Characteristics of this style are rich dramatic colors and elaborate design, which make every element of the painting become part of an almost decorative scheme. This style was widespread until the early Safavid period, but seems to have faded by the middle of the XNUMXth century.

The most important works of the school are the 155 miniatures of Ibn-Husam's Khavar-nama, dating from 1480. Herat's earliest miniatures were in form, a more perfect version of the early Timurid style, which had flourished earlier in the century . Under the patronage of the last Timurid prince, Sultan Hussain ibn Mansur ibn Baiqara (1468 – 1506), Herat flourished like never before and many believe it was here that Persian painting reached its climax.

His style is distinguished by sumptuous color and almost unbelievable precision of detail, perfect unity of composition, striking individual characterization of the human figure, and maximum sensitivity in conveying the atmosphere from the solemn to the playful in narrative painting.

The great surviving masterpieces of the Herat school include two copies of Kalila wa Dimna (a collection of animal fables with moral and political applications), Sa'di's Golestan ('Rose Garden') (1426), and at least a Shah-nama (1429).

As in other periods of 'book art', painting was only one aspect of Islamic decoration. Calligraphy was always considered one of the highest art forms in Islam, and was practiced not only by professional calligraphers but also by the Timurid princes and nobles themselves.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VkP1iHzExtg

The same artist often practiced the arts of calligraphy, illumination, and painting. Mirak Naqqash, for example, started out as a calligrapher, then illuminated manuscripts, and eventually became one of the greatest painters of the Herat court school.

Persian calligraphers excelled at all styles of cursive writing; the elegant large muhaqqaq, the finer rihani (both with sharp ends), the twilight-like ghubar, and the heavy, supple thuluth script. In the late XNUMXth century, 'Umar Aqta' (with his hand amputated), wrote a miniature Qur'an for Timur, which was so small that it could be placed under the socket of a signet ring.

When Timur disapproved because, according to a prophetic tradition, the Word of God was to be written in large letters, the calligrapher produced another copy, each letter measuring a cubit in length.

This was also a time of great development in the decorative arts: textiles (particularly rugs), metalwork, ceramics, etc. Although no rugs have survived, the miniatures offer extensive documentation of the beautiful rugs made in the XNUMXth century. In these, geometric motifs in the Turkish-Asian fashion seemed to be preferred.

Relatively little high-quality goldsmithing has survived from the Timurid dynasty, although again miniatures from the period (whose obsessive detail makes them an excellent guide to contemporary objects) show that jugs with long curved spouts were developed at this time.

A few spectacular but isolated objects hint at this largely defunct industry, including a candlestick base made up of knotted dragon heads and a pair of huge bronze cauldrons.

Of works in gold and silver, except for a few pieces, nothing has survived of what must have been a magnificent production of articles and ornaments in precious metals. The miniatures show gold jewelry sometimes encrusted with stones.

The use of precious and semi-precious stones for household objects became widespread under the direct influence of Chinese models. Jade in particular was used for small bowls, dragon-handled jars, and signet rings. Recent research has shown that the number of surviving Timurid ceramics is not as small as once thought. In the early Timurid period no pottery production center is known.

However, it is true that the Timurid capitals (Mashad and Herat in Khurassan, Bukhara and Samarkand in Central Asia) had large factories, where not only the magnificent tiles that decorated the buildings of the time, but also ceramics, were produced.

Chinese blue and white porcelain (mainly large wide-rimmed bowls and plates), introduced to Persia in the second half of the XNUMXth century, started a new fashion that dominated pottery production throughout the XNUMXth century.

On the white background, lotus flowers, ribbon-shaped clouds, dragons, ducks in stylized waves, etc., were drawn in various shades of cobalt blue. This style continued until the XNUMXth century, when more daring motifs with landscapes and large figures of animals were developed.

From an architectural point of view, few innovations were made during the Timurid period with mosques founded on an old Seljuk plan. The most significant contribution of Timurid architecture; however, it is in its decoration.

The introduction of faience mosaic (tile mosaic) transformed the entire appearance of Timurid architecture and, together with the use of patterned bricks, became the most characteristic feature of architectural decoration. Huge surfaces were decorated with carved arabesque coverings and glazed tiles. The enamel was turquoise or deep blue, with white for the inscriptions.

The Persian Miniature

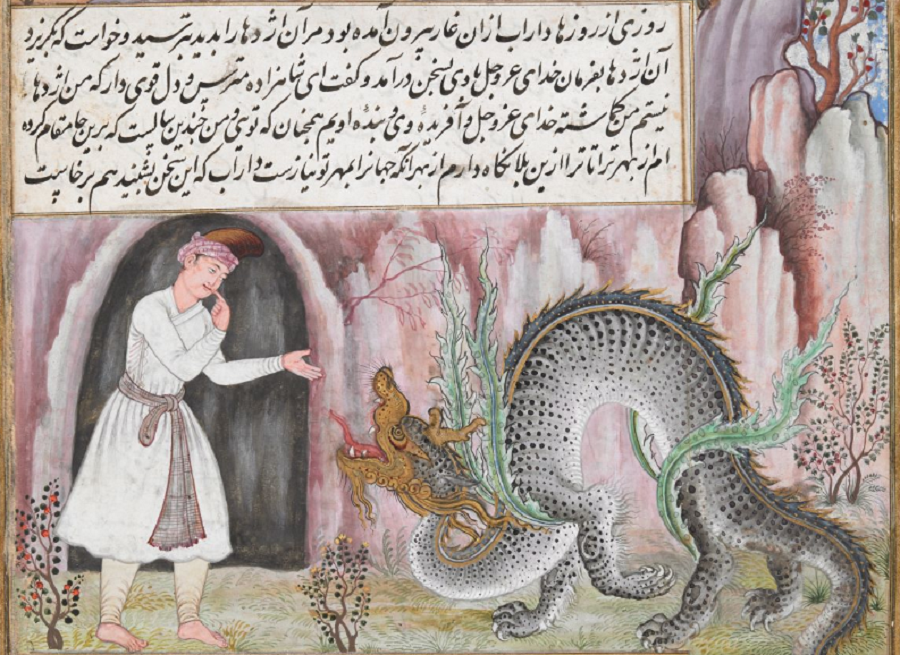

Persian miniature painting began in the Mongol period in the early XNUMXth century, when Persian painters were exposed to Chinese art and Chinese painters worked in the Ilkan courts of Iran. It is not known whether Persian artists went to China before the XNUMXth century; but it is true that Chinese artists imported by the Mongol rulers went to Iran, like those Arghun used to paint the walls of Buddhist temples.

Unfortunately, the works of these artists, as well as the entire collection of secular wall paintings, were lost. Highly artistic miniature painting was the only form of painting to survive this period.

In Ilkanid miniatures, the human figure that had previously been depicted in a robust and stereotyped manner is now shown with more grace and more realistic proportions. As well as, the folds of the curtains gave the impression of depth.

Animals were watched more closely than before and lost their decorative rigidity, mountains lost their soft appearance, and skies became animated with typically curly white clouds shaped like twisted garlands. These influences progressively merged with Iranian paintings and were eventually assimilated into new forms. The main center of Ilkan painting was Tabriz.

Some of the effects of Chinese influence can be seen in Bahram Gur's painting "The Battle with the Dragon" from the famous Demotte "Shah-namah" (The Book of Kings), illustrated in Tabriz in the second quarter of the XNUMXth century. . The details of the mountains and landscape are of Far Eastern origin, as is, of course, the dragon with which the hero is locked in combat.

By using the frame as a window and placing the hero with his back to the reader, the artist creates the impression that the event is really happening before our eyes.

Less obvious, but more important, is the vague and indefinite relationship between the immediate foreground and the distant background, and the composition's abrupt cutoff on all sides. Most of Demotte Shah-namah's miniatures must be considered among the masterpieces of all time, and this manuscript is one of the oldest copies of Ferdowsi's immortal epic poem.

The Shah-namah was frequently illustrated in the Ilkhanid period, probably because the Mongols developed a marked taste for the epic during the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries. Ilkhanate scribes and illuminators brought the art of the book to the fore.

The Mosul and Baghdad schools rivaled Mamluke's best work, and indeed may have laid the groundwork for it. Characteristic of this school is the use of very large sheets (up to 75 x 50 cm, 28" x 20") of Baghdad paper and corresponding large-scale writing, especially muhaqqaq.

the safavids

The Safavid dynasty, of Turkish origin, is generally considered to have lasted from 1502 to 1737, and under the rule of Shah Isma'il Shiite doctrine prevailed as the state religion. The Safavids continued the Ilkani attempts to foster closer diplomatic ties with European powers, in order to cement alliances against the Ottomans. As a result of this closer relationship, the Safavids opened the door to European influence.

From the description of Western travelers it is known that wall paintings once existed; with battle scenes in Shiraz showing the capture of Hormuz from the Portuguese, as well as erotic scenes in Julfa, and pastoral scenes in the Hazar Jarib palace in Isfahan.

In the interior of the Safavid palaces, pictorial decoration was used alongside traditional decorations on Kashi or pottery. Early Safavid painting combined the traditions of Timurid, Herat and Turkoman Tabriz to reach a peak of technical excellence and emotional expressiveness, which for many is the greatest age of Persian painting.

book arts

The masterpiece of the period is the Shahnama-yi Shahi (The King's Book of Kings, formally known as the Houghton Shah-nama) with its 258 paintings, which was the most abundantly illustrated Shah-nama recorded in all of Persian history. .

Herat was the great center of Iranian miniature painting of the Timurid period, but in 1507 after its capture by the Safavids the leading artists emigrated, some to India and others to the Safavid capital Tabriz or the Shaybanid capital Bukhara.

One of the main innovations of the Bukhara miniaturists was the introduction of plant and animal motifs in the margins of their miniatures. It was in Tabriz, the other main miniature center of the period, that in 1522 Shah Ismail appointed the famous director of his library in Behzad.

Characteristic features of the Tabriz school can be seen in illustrations from a manuscript of Nezami's Khamsa; executed between 1539 and 43 by Aqa Mirak of Isfahan, the student of him Sultan Muhammad, Tabriz artists Mir Sayyid 'Ali, Mirza' Ali and Muzaffar 'Ali. Tabriz's miniatures exploit the full color range, and his compositions are complex and full of figures that fill space.

Shah Ismail's successor, hired Shah Tahmasp himself as a painter by enlarging the royal workshop. However, during the latter part of the XNUMXth century, Shah Tahmasp became a religious extremist, lost interest in painting, and ceased to be a patron. This was the beginning of the end of the luxury book.

Many of the best artists left the court, some to Bukhara, others to India where they were instrumental in the formation of a new style of painting, the Mughal School. The artists who remained moved from producing richly illustrated manuscripts to separate drawings and miniatures for less wealthy patrons.

Towards the end of the 1597th century, with the transfer of the capital to Shiraz (XNUMX), an official deregulation of the traditional code of book painting took place. Some painters turned to other media, experimenting with book covers in lacquer or full-length oils.

If earlier paintings had been about man in his natural environment, those from the late XNUMXth and early XNUMXth centuries are about man himself. Work from this period is dominated by large-scale depiction of seedy dervishes, Sufi sheikhs, beggars, merchants… with satire as the driving force behind most of these images.

Some of the same artists lent their talents to a completely different genre of painting, sensual and erotic, with scenes of lovers, voluptuous women, etc. They were extremely popular and were produced mechanically with the minimum of effort.

Two main factors influenced artists between 1630 and 1722; Riza's works and European art. In Riza's drawings, the contouring of basic forms is accompanied by an obsession with folds, which normally serve to emphasize the sensuous curvature of the body form, but often go to the point of complete abstraction.

In a country with a strong calligraphic tradition, writing and drawing are always interconnected, but at this time the link seems to have been particularly strong, so that drawing takes on the physical appearance of Shikastah or Nasta'liq calligraphy.

Towards the second half of the XNUMXth century, when Shah Abbas II sent the painter Muhammad Zaman to study in Rome, the need to find new forms of expression awoke in artists. Muhammad Zaman himself returned to Persia completely under the influence of Italian painting techniques. However, this was not a breakthrough in his painting style. In fact, his miniatures for the Shah-nama are generally banal and lack a sense of balance.

When it comes to architecture, the place of honor is the expansion of Isfahan, devised by Shah Abbas I from 1598, which is one of the most ambitious and innovative urban planning schemes in Islamic history.

In architectural decoration great importance was attached to calligraphy, which was transformed into an art of monumental inscriptions, a development of particular artistic merit in the art of kashi. Its main exponent was Muhammad Riza-i-Imami who worked in Qum, Qazvin and above all, between 1673 and 1677 in Mashad.

Ceramics

The death of Shah Abbas I in 1629 marked the beginning of the end of the golden age of Persian architecture. Glazed brick detail at the Sheikh Lutfullah Mosque in Isfahan, showing Quranic text in stylized Kufic characters.

The last decade of the XNUMXth century saw a vigorous revival of the pottery industry in Iran. New types of Chinese-inspired Kubachi polychrome blue and white pottery were developed by Safavid potters, perhaps due to the influence of the three hundred Chinese potters and their families who settled in Iran (in Kerman) by Shah Abbas I.

Ceramic tiles were specially produced, in Tabriz and in Samarkand. Other types of pottery include bottles and jars from Isfahan.

the persian rug

Textiles were greatly developed during the Safavid period. Isfahan, Kashan and Yezd produced silks and Isfahan and Yezd produced satin, while Kashan was famous for its brocades. Persian clothing of the XNUMXth century often had floral decoration on a light background, and ancient geometric motifs gave way to the depiction of pseudo-realistic scenes filled with human figures.

Carpets occupy the leading position in the textile field, with key weaving centers in Kerman, Kashan, Shiraz, Yezd and Isfahan. There was a wide variety of types such as the hunting rug, the animal rug, the garden rug, and the vase rug. The strong pictorial character of so many Safavid rugs owes much to Safavid book painting.

Metallurgy

In metalwork, the engraving technique developed in Khurassan in the XNUMXth century remained popular well into the Safavid era. Safavid metalwork produced important innovations in form, design, and technique.

They include a kind of tall octagonal torch-bearer on a circular pedestal, a new type of Chinese-inspired jug, and the almost complete disappearance of Arabic inscriptions in favor of those containing Persian poetry, often by Hafez and Sa'di.

In gold and silver work, Safavid Iran specialized in the production of swords and daggers, and of gold vessels such as bowls and jugs, often set with precious stones. Safavid metalwork, like so many other visual arts, remained the standard for later artists in the Zand and Qajar periods.

Zand and Qajar periods

The Qajar dynasty that ruled Persia from 1794 to 1925 was not a direct continuation of the Safavid period. The invasion of the Afghan Ghilzai tribes with the 1722 occupation of the Safavid capital, Isfahan, and the eventual collapse of the Safavid Empire in the following decade plunged Iran into a period of political chaos.

With the exception of the Zand interval (1750-79), the history of 1796th-century Iran was marred by tribal violence. This ended with the coronation of Aqa Muhammad Khan Kayar in XNUMX, which marked the beginning of a period of political stability characterized by a revival of cultural and artistic life.

Kayar painting

The Zand and Qajar periods saw a continuation of the oil painting introduced in the XNUMXth century and the decoration of lacquer boxes and bindings. Illustrated historical manuscripts and single-page portraits were also produced for a variety of patrons, in a style consistent with that of Muhammad Ali (son of Muhammad Zaman) and his contemporaries.

Although the excessive use of shadows sometimes gives these works a dark quality, they show a better understanding of the play of light (coming from a single source) in three-dimensional forms.

The evolution of Persian art in the 1750th and 79th centuries can be divided into different phases, beginning with the reign of Karim Khan Zand (1797-1834), Fath Ali Shah (1848-96), and Nasir ad-Din Shah (XNUMX-XNUMX). ).

During the Zand period, Shiraz became not only the capital but also the center of artistic excellence in Iran, and Karim Khan's building program in the city attempted to emulate Shah Abbas's Isfahan. Shiraz was endowed with fortifications, palaces, mosques and other civil amenities.

Karim Khan was also a noted patron of painting, and the Safavid-European tradition of monumental figure painting was revived under the Zand dynasty, as part of a general revival of the arts. Zand artists were just as versatile as their predecessors.

In addition to developing life-size paintings (murals and oil on canvas), manuscripts, illustrations, watercolours, lacquer works and enamels of the Safavid dynasty, they added a new medium that of water drawing.

In his paintings, however, the results often seemed rigid, as Zand artists, to correct what they saw as an overemphasis on three-dimensionality, attempted to lighten the composition by introducing decorative elements. Pearls and various jewels were sometimes painted on the headdress and clothing of the subjects.

royal portraits

Karim Khan, who preferred the title of Regent (Vakil) to that of Shah, did not demand that his painters embellish their appearance. He was happy to be shown in an informal and unassuming gathering in a modest architectural setting. The tone of these Zand paintings contrasts sharply with later images of Fath Ali Shah (the second of the seven rulers of the Qajar dynasty) and his court.

There is an unquestioned Zand heritage in Kayar's early Persian art. The founder of the Qajar dynasty, Aqa Muhammad Khan, is known to have decorated his Tehran courtroom with paintings looted from the Zand palace and Mirza Baba (one of Karim Khan's court artists) became the first laureate painter of Fath 'Ali Shah.

Fath Ali Shah was particularly receptive to ancient Iranian influences, and numerous rock reliefs were carved in neo-Sassanid style, depicting the Qajar ruler in the guise of Khosroe. The best known reliefs are found at Chashma-i-Ali, at Taq-i-Bustan and in the vicinity of the Koran Gate in Shiraz.

Under Fath Ali Shah there was a clear return to tradition. However, at the same time the European court style of the late XNUMXth century appeared in the palaces of Tehran. European influences are also mixed with Sassanian and Neo-Achaemenid themes in the figurative carved stucco of this period (as can be seen in many houses in Kashan).

He also used large-scale frescoes and canvases to create an imperial personal image. Portraits of princes and historical scenes were used to adorn their new palaces and were often shaped like an arch to fit into an arched space on a wall. Fath Ali Shah also distributed several paintings to foreign powers such as Russia, Great Britain, France, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The interplay of folk style and European influence is even more apparent in the painting, with Flemish and Florentine elements appearing in Madhi Shirazi's (1819-20) painting of the "Mazda" Dancer. With the introduction of large-scale printing and painting, some of Kayar's best miniature artists turned to lacquer work such as: book bindings, coffins, and pen cases (qalamdan).

The style is particularly cosmopolitan and characteristic of a court that tried to combine the styles of Persepolis, Isfahan and Versailles.

In the second half of the XNUMXth century, Nasir al Din Shah, in addition to collecting European works of art, supported a local school of portraiture that abandoned the style of Fath Ali Shah in favor of a European-influenced academic style. The works of these local artists ranged from state portraits in oil to watercolors of unprecedented naturalism.

Photography now began to have a profound impact on the development of Persian painting. Shortly after its introduction to Iran in the 1840s, Iranians quickly adopted the technology. Nasir-al Din Shah's minister of publications, I'timad al-Saltaneh, stated that photography had greatly served the art of portraiture and landscape by reinforcing the use of light and shadow, precise proportions, and perspective.

In 1896 Nasir al-Din Shah was assassinated and within ten years Iran had its first constitutional parliament. This period of political and social change saw artists explore new concepts, both within and beyond the confines of imperial portraiture.

In the double portrait of Muzaffar al-Din Shah, the prematurely aged ruler is shown resting one arm on a staff and the other on the supporting arm of his premier. The artist here conveys both the fragile health of the Monarch and the Monarchy. The most important artist of the late Ajar period was Muhammad Ghaffari, known as Kamal al-Mulk (1852-1940), who advocated a new naturalistic style.

Tiles

Kayar tiles are usually unmistakable. The repertoire of so-called dry rope tiles shows a completely new departure from that of the Safavid era. For the first time, representations of people and animals constitute the main theme.

There are also hunting scenes, illustrations of the battles of Rostam (the hero of the national epic, Shah-nama), soldiers, officials, scenes of contemporary life, and even copies of European illustrations and photographs.

The Kayar technique par excellence, again driven by European influence, in this case Venetian glass, was the mirror. Mugarnes cells facing mirrors produced an original and spectacular effect, as can be seen in the Golestan Palace in Tehran or in the Hall of Mirrors in the Mashad Shrine.

Fabrics

In the field of applied arts, only weaving remained of importance that extended beyond the borders of Iran, and during the Qajar period, the carpet industry gradually revived on a larger scale. Although many traditional designs were retained, they were expressed in different ways, often on a smaller scale than their Safavid prototypes, with the use of a brighter range of colours.

Music

The original Persian music contains what is the Dastgah (musical modal system), melody and Avaz. This type of contusica has existed before Christianity and came mainly by word of mouth. The nicer and easier parts have been kept so far.

This type of music influenced most of Central Asia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Turkey and Greece. In addition, each of them also contributed to the formation of it. Among the famous Persian musicians of ancient Iran, are:

- Barbod

- Nagisa (Nakisa)

- ramtin

The carvings on the walls of the ancient cave show Iranians' interest in music from the earliest times. Traditional Iranian music as mentioned in the books has influenced world music. The basis of the new European musical note is in accordance with the principles of Mohammad Farabi, a great Iranian scientist and musician.

The traditional Persian music of Iran is a collection of songs and melodies created over centuries in this country and reflects the morals of Iranians. On the one hand, the elegance and special form of Persian music persuade listeners to think and reach into the immaterial world. On the other hand, the passion and rhythm of this music are rooted in the ancient and epic spirit of Iranians, which drives the listener to move and strive.

Literature

Persian literature is a body of writings in New Persian, the form of the Persian language written since the XNUMXth century with a slightly extended form of the Arabic alphabet and with many Arabic loanwords. The literary form of New Persian is known as Farsi in Iran, where it is the official language of the country and is written in the Cyrillic alphabet by Tajiks in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

For centuries, New Persian has also been a prestigious cultural language in Western Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and Turkey. Iranian culture is perhaps best known for its literature, which emerged in its current form in the XNUMXth century. The great teachers of the Persian language:

- Ferdowsi

- Neami Ganjavi

- Ḥafeẓ Shirazi

- Hours

- Moulana (Rumi)

Who continue to inspire Iranian authors in the modern era. Undefined Persian literature was deeply influenced by Western literary and philosophical traditions in the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries, but remains a vibrant medium for Iranian culture. Whether in prose or poetry, it also came to serve as a vehicle for cultural introspection, political dissent, and personal protest for such influential Iranian writers as:

- Sadeq Hedayat

- Jalal Al-e Ahmad

- Sadeq-e Chubak

- sohrab sepehri

- Mehdi Akhavan Saales

- ahmed shamlu

- Forough Farrokhzad.

Calligraphy

As mentioned in all the previous content, calligraphy in Persian art in its beginnings was used for a merely decorative nature, so it was very common for artists to use it to leave this type of art in: metal vessels, pottery, as well as in various ancient architectural works. The American writer and historian Will Durant gave a very brief description of it:

"Persian calligraphy had an alphabet of 36 characters, which the ancient Iranians generally used pencils, a ceramic plate and skins to capture."

Among the first works with great value in the present, in which this type of delicate technique of illustrations and calligraphy was also used, we can mention:

- The Qur'an Shahnameh.

- Divan Hafez.

- Golestan.

- Bostan.

Most of these texts are kept and preserved in various museums and by collectors around the world, among the institutions that guard these are:

- The Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg.

- Freer Gallery in Washington.

Additionally, it is important to emphasize that Persian art in this category used several styles of calligraphy, among which the following stand out:

- Shekasteh

- Nasta'liq

- naskh

- muhaqqaq

Decorative tiles

The tiles were a fundamental piece for Persian architecture in terms of the construction of mosques, for this reason the predominance of this element can be seen, for example, in Isfahan where the favorite was the one with blue tones. Among the ancient places most noted for the production and use of Persian tile are Kashan and Tabiz.

Reasons

Prey art has demonstrated over a long period of time, a unique creation of designs that have been used to adorn various objects or structures, possibly motivated by:

- The nomadic tribes, who had a technique to create geometric designs widely used in kilim and gabbeh designs.

- The idea about advanced geometry influenced by Islam.

- The consideration of oriental designs, which are also reflected in India and Pakistan.

Other crafts linked to Persian art

Persian art can also be seen reflected in other societies that due to the proximity to Persia were influenced by this culture, although in some of them at present there are no palpable objects of its artistic manifestation, its existence can be recognized. and the contribution of his art. Among these companies, we can mention:

- The Aryans or Indo-European Iranians, who arrived on the plateau during the second millennium BC, at Tappeh Sialk.

- The pastoral culture of Marlik.

- The inhabitants of the ancient district near Persia, Mannai.

- The Medes, an Indo-European tribe who, like the Persians, had entered western Iran.

- The Ghaznavids, who take their name from the dynasty founded by the Turkish sultan Sabuktagin, whose leaders ruled from Ghazni (in what is now Afghanistan).

If you found this article about Persian art and its history interesting, we invite you to enjoy these others: