We only know a small part of the general panorama of the advances of this culture since only four Mayan codices they have been able to survive and are the greatest treasure of a lost civilization, evidence of the distinctive and highly developed culture of this Mesoamerican people.

Mayan codices

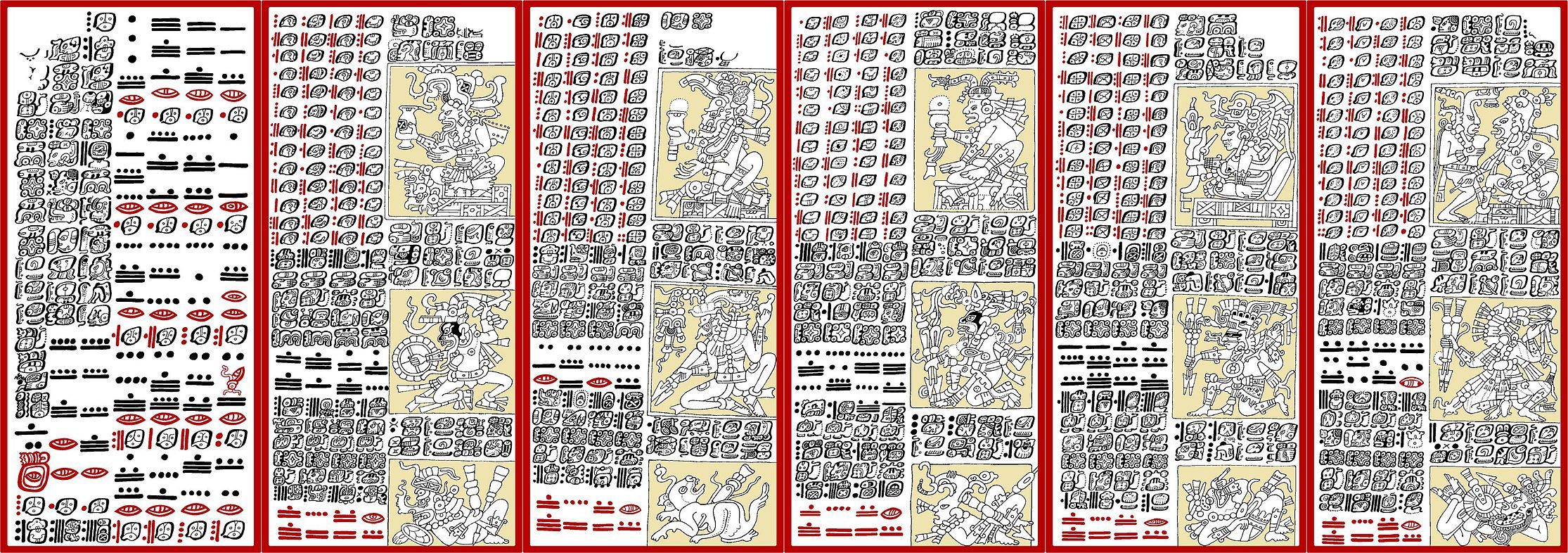

The Mayan Codices are illuminated manuscripts folded on amate paper, in which information is recorded about the life of the Mayans, but also about religion, mysticism, astronomy and mathematics. They were probably priestly manuals. The Mayans had a highly developed writing system of images, letters and number of characters.

The Mayan codices are hieroglyphic manuscripts of the Mayan civilization. Technically, the Mayan codex is an accordion-folded strip of Mesoamerican paper, made from the tow of the amate plant. The folds of the accordion could be covered with images and inscriptions on the front and back, sometimes the back was not filled with text and images. The texts were not intended to be read in a row, but were structurally divided into thematic blocks.

The substantially preserved Mayan codices are priestly books, which are dedicated to ritual, astronomy and astrology, prophecies and divination practices, calculation of agricultural and calendar cycles. With their help, the priests interpreted the phenomena of nature and the actions of divine forces and carried out religious rites. Maya codices were in daily priestly use and were often placed in the tomb after the owner's death.

From

At the time of the Spanish conquest of Yucatan in the 1562th century, there were many similar books that were later destroyed on a large scale by the conquistadors and their priests. Thus, the destruction of all the books present in Yucatan was ordered by Bishop Diego de Landa in July XNUMX. These codices, as well as the numerous inscriptions on monuments and stelae that are still preserved today, constituted the written archives of civilization Maya.

On the other hand, it is very likely that the variety of themes they treated differed significantly from the themes preserved in stone and in buildings; with its destruction we lost the chance to glimpse key areas of Mayan life. Today only four definitively authentic Mayan books exist today. The four codices were probably created in the last few centuries before the Spanish conquest, the Postclassic period.

Due to the linguistic and artistic similarities with the local inscriptions, it is assumed that the three long-known books (Madrid, Dresden, Paris) come from the same region, the northern part of the Yucatan peninsula. How they arrived from Yucatan to Europe is unknown, despite intense research. The last book discovered (Mexico) comes from an excavation, Chiapas is supposed to be the place of origin.

Preserved Mayan codices

Due to the time of the conquistadors and the destruction of all "pagan" objects (especially by Diego de Landa in 1562), only four definitively authentic Mayan books exist today. To distinguish them, they have all been named after their subsequent storage location:

- Madrid Codex (also Codex Tro-Cortesianus)

- Dresdner Codex (also Codex Dresdensis)

- Paris Codex (also Codex Peresianus)

- Mayan Codex of Mexico (formerly Codex Grolier)

Codex of Madrid

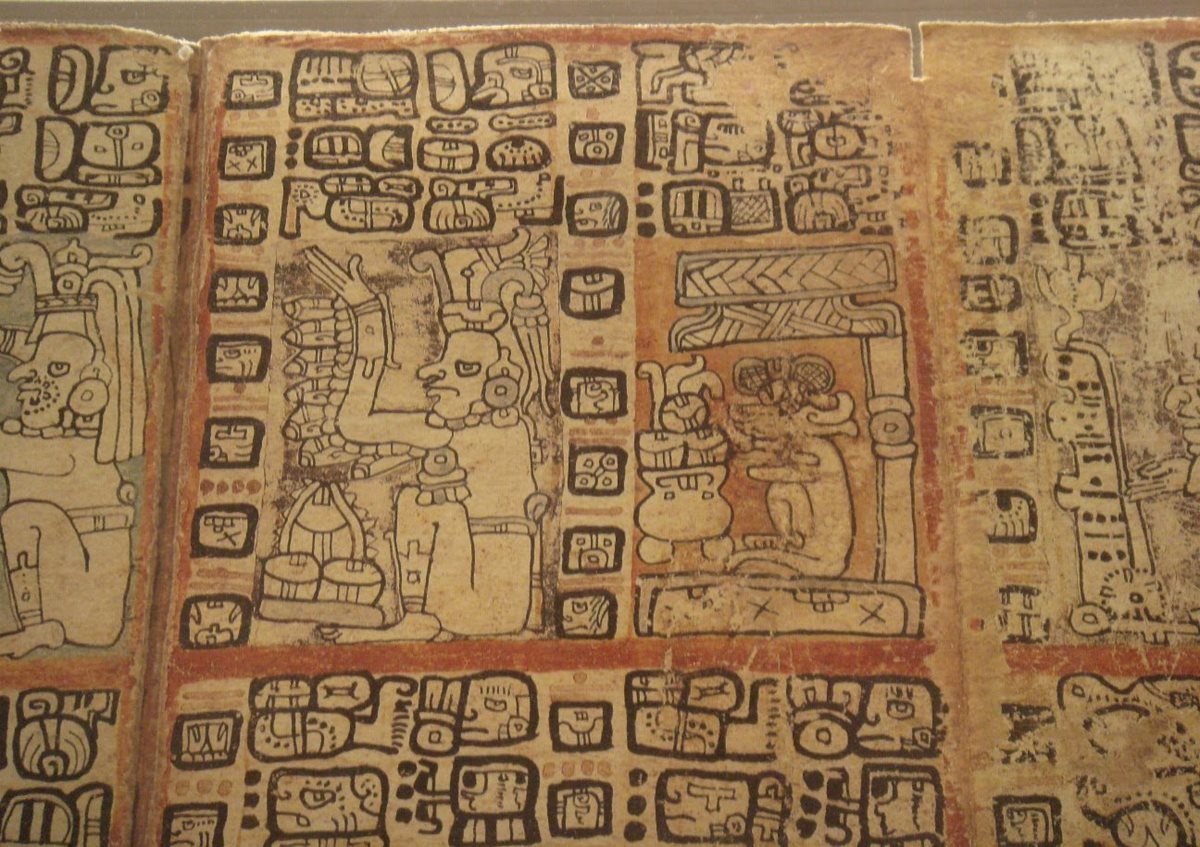

The codex is a folding book of one hundred and twelve pages (fifty-six sheets) made of Amate paper, which is also covered with a fine layer of stucco. With a side height of 22,6 centimeters and a length of 6,82 meters, it is the longest of the four Mayan codices that have been preserved. The manuscript was discovered in two parts in different places in Spain in the 1860s.

Although the quality of execution is inferior, the Madrid Codex is even more varied than the Dresden Codex and must have been produced by eight different scribes. It is in the Museo de América in Madrid, Spain, it must have been sent to the Spanish court by Hernán Cortés. There are one hundred and twelve pages, previously divided into two separate sections known as the Codex Troano and the Codex Cortesianus and assembled in 1888.

The Madrid manuscript contains tables, instructions for religious ceremonies, almanacs, and astronomical tables (Venus tables). It allows to know the religious life of the Mayans. Contains an eleven page section dealing with beekeeping. Numerous illustrations show religious practices, human sacrifice, and many everyday scenes such as weaving, hunting, and war. Presumably the book was used for astrological prophecies and allowed the dates for sowing and harvesting and the timing of sacrificial rituals to be determined.

The Dresden Codex

The Dresden Codex can be found in the book museum of the Saxony State and University Library in Dresden, Germany. It is the most elaborate of the Mayan codices, as well as an important work of art. Many sections are ritualistic (including so-called "almanacs"), others are astrological in nature (eclipses, Venus cycle).

The codex is written on a long sheet of paper folded to produce a thirty-nine-page book, written on both sides. It must have been written shortly before the Spanish conquest. It somehow found its way to Europe and was bought by the library of the royal court of Saxony in Dresden in 1739.

The Paris Codex

The Paris Codex is kept in the National Library of France and is an almanac of prophecies. It was found in a garbage can in the library in 1859. It measures 1,45 meters, has twenty-two pages, and is the worst preserved of the four manuscripts in Mayan script. The letters and painting can only be seen in the middle of the pages.

The last pages describe thirteen constellations of the zodiac cycle. Some pages contain information about the fifty-two-year cycle, where the 365-day Haab calendar and the 260-day Tzolkin calendar return to their common starting point. Since the calendar cycles refer to the period 731 to 787, the Paris Codex could also be a copy of the classical period. It is dated between 1300 and 1500.

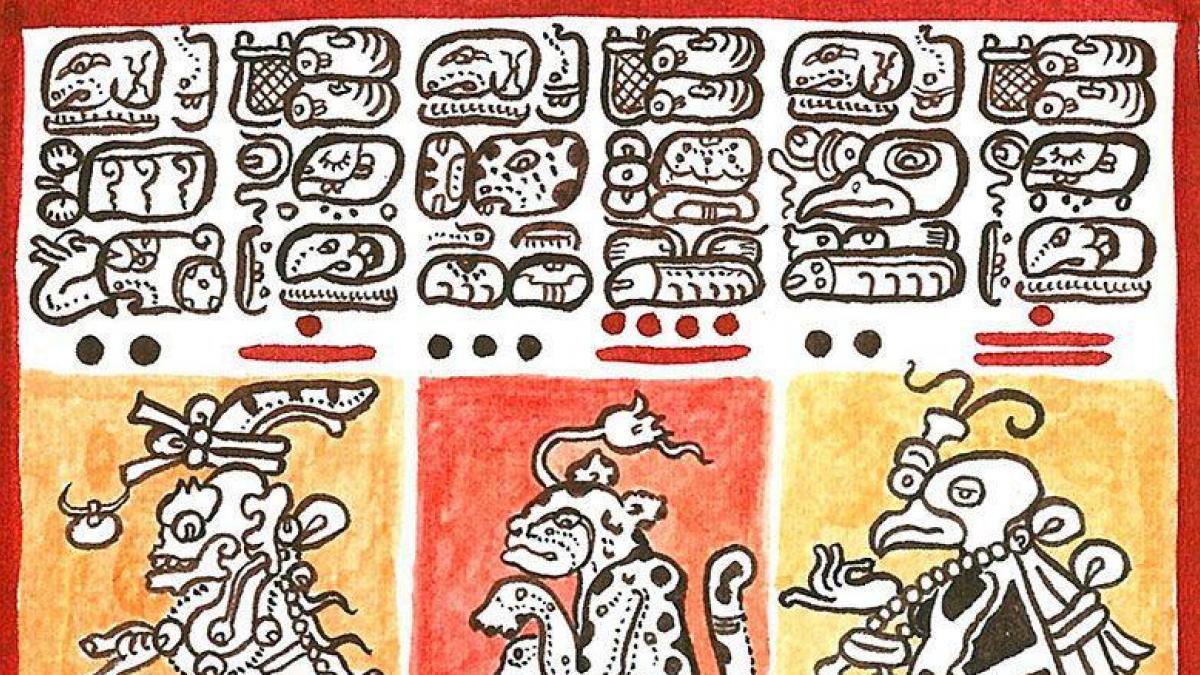

Mayan Codex of Mexico

The codex, along with other artifacts, is believed to have come from a robbery at a cave dig in Chiapas in the 1960s. Mexican collector Dr. José Sáenz was abducted by vendors in a small plane to a location near the Sierra of Chiapas and Tortuguero. There they showed him the finds and he bought the fragment of the codex. The codex was once exhibited in 1971 at the Grolier Club in New York. Dr. Sáenz donated it to the Government of Mexico and today it is preserved but not on display at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

The codex was recognized as a Venus Astrological Almanac, which predicted the celestial position of the planet Venus over a period of one hundred and four years. It is similar to the part of the Dresden Codex that relates to Venus. While the Dresden Codex only describes Venus as the morning star and the evening star, all four situations are recorded in the Mexico City codex: as the morning star, disappearing at superior conjunction, as the star evening and again invisible in the lower conjunction.

Each side shows a figure/deity facing left, holding a weapon and usually a rope with a prisoner. Pages five and eight show a figure shooting an arrow at a temple. The figure shown on page seven may show a warrior standing passively in front of a tree. Pages one and four suggest K'awiil, and pages two, six, and page ten, which consists of two fragments, suggest a death god.

Here are some links of interest: