In the native faith of Japan, it is believed that there is a Kami or a god for everything being linked with virtues, rituals, professions, meteorological phenomena, even trees and mountains. Therefore, we want to invite you through this publication to meet some japanese gods and a bit of the mythological history of each one.

What are the Japanese Gods?

When we refer to the Japanese gods, we must understand that much of the mythology and pantheon is derived from the traditional folklore of Shintoism, which is one of the main religions of Japan. And interestingly enough, like Hinduism, Shinto or kami-no-michi ("the way of the gods") is a polytheistic mode of religion resulting from Japan's highly pluralistic culture throughout history.

In essence Shinto, without any proclaimed founder or prescribed principles, can be seen as the evolution of the local animal beliefs of the Yayoi culture (300 BC – 300 AD) which were more influenced by Buddhism and even the Hinduism throughout the centuries. Given the nature of these localized folklores (mixed with the myths of revered entities from Buddhism and Hinduism), the Japanese gods are deities based primarily on the kami, the mythical spirits and supernatural beings of the earth.

In terms of history, the earliest of these mythologies was documented in written form in the early XNUMXth century, thus serving as a standardized (or at least generalized) template of the Shinto pantheon for most of Japan. To that end, most of the mythical narratives of the Japanese gods are derived from the codified books:

- Kojiki (circa 708-714 AD)

- Nihon Shoki (circa 720 AD)

- XNUMXth-century Kogoshui (who compiled the oral folklore missing from the previous two codified documents).

Next, some Japanese gods are presented with part of the mythological narrative that surrounds them, and in turn the attributions of each one are specified, these are:

Izanami and Izanagi – The primordial Japanese gods of creation

Like most creation myths, the Japanese Shinto myth also consists of the primordial gods called Izanagi (Izanagi no Mikoto or 'the one who invites') and Izanami (Izanami no Mikoto or 'the one who invites'), the duo of brother and sister who are perceived as the divine beings who brought order to the sea of chaos under the sky, creating the first landmass in the form of Onogoro Island.

Interestingly, most accounts agree that they were directed to do so by an even earlier generation of kami (godlike beings) who resided in the sky plain. Even more intriguing is the way the duo created the landmass, by standing on the bridge or stairway to heaven (Ama-no-hashidate) and churning the chaotic ocean below with their jewel-encrusted spear, giving rise to the Onogoro Island.

However, despite their apparent ingenuity things soon fell out of favour, and their first union created a misshapen offspring: the god Hiruko (or Ebisu, discussed later in the article). Izanagi and Izanami continued to create more land masses and gave birth to other divine entities, thus giving rise to the eight main islands of Japan and more than 800 kami.

Unfortunately, in the arduous process of creation, Izanami died from the burning pain of giving birth to Kagutsuchi, the Japanese god of fire; and consequently she is sent to the underworld (Yomi). Grief-stricken Izanagi followed his sister Izanami to the underworld and even managed to convince the previous generation of gods to allow him to return to the realm of the living.

But the brother, impatient to wait too long, takes a premature look at his sister's "undead" state, which was more like a decomposing corpse. A host of angry thunder kami attached to this body chased Izanagi out of the underworld, and he nearly escaped Yomi by blocking the entrance with a huge stone.

This was later followed by a cleansing ritual, by which Izanagi inadvertently created even more Japanese gods and goddesses (Mihashira-no-uzunomiko), such as Amaterasu the sun goddess who was born from the washing of her left eye; Tsuki-yomi the moon god who was born from the washing of her right eye, and Susanoo the storm god who was born from her nose. To that end, in Shinto culture cleansing (harai) is an important part of the ritual before entering holy shrines.

Yebisu – The Japanese god of luck and fishermen

As we mentioned in the previous post Hiruko, the first child of the primordial duo Izanagi and Izanami, was born in a deformed state, which according to the mythical narrative was due to a transgression in their marriage ritual. However, in some narratives Hiruko was later identified with the Japanese god Yebisu (possibly in medieval times), a deity of fishermen and luck. In that sense, the myth of Yebisu was possibly modified to accommodate his (and quite indigenous) divine lineage among the Japanese kami.

In essence, Yebisu (or Hiruko), having been born without bones, was said to have drifted in the ocean at the age of three. Despite this immoral judgment, the boy luckily somehow managed to disembark with a certain Ebisu Saburo. The boy then grew up through various hardships to call himself Ebisu or Yebisu, thus becoming the patron god of fishermen, children, and most importantly, wealth and fortune.

In relation to this latter attribute, Yebisu is often regarded as one of the main deities of the Seven Gods of Fortune (Shichifukujin), whose narrative is influenced by local folklore as opposed to foreign influence.

As for performances, despite his numerous adversities Yebisu maintains his jovial humor (often called the "god of laughter") and wears a tall, pointed cap folded in the middle called a kazaori eboshi. On an interesting note, Yebisu is also the god of jellyfish, given his initial boneless form.

Kagutsuchi: the Japanese god of destructive fire

The Japanese god of fire Kagutsuchi (or Homusubi - "he who lights the fire"), was another descendant of the primordial Izanagi and Izanami. In a tragic twist of fate, her burning essence burned her own mother Izanami, leading to her death and her departure to the underworld. In a fit of rage and revenge, his father Izanagi proceeded to cut off Kagutsuchi's head, and the spilled blood led to the creation of more kami including martial thunder gods, mountain gods, and even a dragon god.

In a nutshell, Kagutsuchi was considered to be the ancestor of various distant, powerful, and powerful deities who even carried out the creation of iron and weapons in Japan (possibly reflecting foreign influence on Japan's different weaponry).

As for the history and cultural side of matters, Kagutsuchi as the god of fire was perceived as an agent of destruction for Japanese buildings and structures typically made of wood and other combustible materials. Suffice it to say that in the Shinto religion, he becomes the center of different appeasement rituals, with a ceremony belonging to the Ho-shizume-no-matsuri, an imperial custom that was designed to ward off the destructive effects of the Kagutsuchi for six months.

Amaterasu – The Japanese goddess of the rising sun

Amaterasu or Amaterasu Omikami ('the celestial kami that shines from the sky'), also known by her honorific title Ōhirume-no-muchi-no-kami ('the great sun of the kami'), is worshiped as the goddess of the sun and the ruler of the kami realm: the High Heavenly Plain or Takama no Hara. In many ways, as queen of the kami she upholds the greatness, order, and purity of the rising sun, while also being the mythical ancestor of the Japanese imperial family (thus alluding to her mythical lineage in Japanese culture). ).

His epithet suggests his role as leader of the gods, with rule granted directly by his father Izanagi the creator of many Japanese gods and goddesses. In that sense, one of the crucial Shinto myths tells of how Amaterasu herself as one of the Mihashira-no-uzunomiko, was born from the cleansing of Izanagi's left eye (as mentioned above).

Another popular myth concerns how Amaterasu locked herself in a cave after having a violent altercation with her brother, Susanoo the storm god. Unfortunately for the world, his radiant aura (personifying the shining sun) was hidden, thus covering the lands in total darkness. And it was only after a series of friendly distractions and invented jokes by the other Japanese gods that he was convinced to leave the cave, which once again resulted in the arrival of radiant sunlight.

Lineage-wise in cultural terms, the Japanese imperial line is mythically derived from Amaterasu's grandson Ninigi-no-Mikoto, who was offered rulership of Earth by his grandmother. On the historical side of matters, Amaterasu (or his equivalent deity) had always been important in the Japanese lands, with many noble families claiming the lineage of the sun deity. But its prominence increased considerably after the Meiji Restoration, in accordance with the tenets of the Shinto state religion.

Tsukiyomi – The Japanese god of the moon

In contrast to many Western mythologies, the Moon deity in Japanese Shintoism is a man, given the epithet Tsukiyomi no Mikoto or simply Tsukiyomi (tsuku probably means "moon month" and yomi refers to "reading"). He is one of the Mihashira-no-uzunomiko born from the washing of Izanagi's right eye, which makes him the brother of Amaterasu the sun goddess. In some myths, he is born from a white copper mirror held in Izanagi's right hand.

As for the mythical narrative, Tsukiyomi the god of the moon married his sister Amaterasu the goddess of the sun, thus allowing the union of the sun and the moon in the same sky. However, the relationship was soon broken when Tsukiyomi killed Uke Mochi the goddess of food.

The heinous act was apparently carried out in disgust when the moon god witnessed Uke Mochi spitting out various foods. In response, Amaterasu broke away from Tsukiyomi by moving to another part of the sky thus making day and night completely separate.

Susanoo: the Japanese god of the seas and storms

Born from the nose of Izanagi the father of the Japanese gods. Susanoo was a member of the Mihashira-no-uzunomiko trio, which made him the brother of Amaterasu and Tsukiyomi. In terms of his attributes, Susanoo was perceived as a temperamental and disheveled kami who is prone to chaotic mood swings, thus alluding to his power over ever-changing storms.

Mythically, the fickle nature of his benevolence (and malevolence) also extends to the seas and winds near the coast, where many of his shrines are in southern Japan. Speaking of myths, Susanoo is often celebrated in Shinto folklore as the cunning champion who defeated the evil dragon (or monstrous serpent) Yamata-no-Orochi by cutting off all ten of his heads after drinking them with alcohol.

After the encounter, he retrieved the famous sword Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi and also won the hand of the woman he saved from the dragon. On the other hand, Susanoo is also portrayed in a somewhat negative light (thus reflecting the storm god's chaotic nature), especially when it comes to his rivalry with Amaterasu the leader and sun goddess of the kami.

On one occasion their mutual defiance turned sour, and Susanoo's anger went on a rampage destroying the sun goddess's rice fields and even killing one of her attendants. In response, the angry Amaterasu retreated into a dark cave, thus snatching her divine light from the world, while the ever-boisterous Susanoo was banished from heaven.

Raijin and Fūjin: the Japanese weather gods

Speaking of storms and duality of character, Raijin and Fujin are considered the powerful kami of the elements of nature that can be favorable or unpleasant to the difficulties of mortals. To that end, Raijin is the deity of thunder and lightning who unleashes his tempests by wielding his hammer and beating the drums. Interestingly, Raijin is depicted as having three fingers, each representing the past, present, and future.

Fujin on the other hand, is the fearsome and monstrous kami of the winds, carrying his fair share of gales and gusts in a bag on his shoulders. According to some myths, it was Fujin who saved Japan during the Mongol invasions by unleashing a typhoon on the approaching fleet, which was later named kamikaze ("divine wind").

However, other myths related to the samurai call it the work of Hachiman the god of war (discussed later in the article). Interestingly, there is a hypothesis as to how Fujin was possibly inspired by the Greco-Buddhist deity Wardo (worshipped along the Silk Road), who in turn was derived from the Greek wind god Boreas.

Ame-no-Uzume: the Japanese goddess of dawn and dance

The playful female deity of dawn (which in a way made her the assistant of Amaterasu, the sun deity), Ame-no-Uzume also embraced the spontaneity of nature. This last aspect made her the patron goddess of creativity and the performing arts, including dance. To that end, one of the central myths in Shinto concerns how Amaterasu, the sun goddess, locked herself in a dark cave after a fight with Susanoo, the storm god; which resulted in the coming of darkness over the heavens and the earth.

So, in an attempt to distract the other anxious kami Ame-no-Uzume, by virtue of her inherent spontaneity and creativity, she covered herself with leaves from the Sakaki tree and then began making joyful cries and followed up with a joyful dance overhead. of a platform; she even resorted to taking off her clothes, which caused amusement among the other gods who began to roar with joy and laughter. The resulting joy directed Amaterasu's curiosity, and she finally emerged from his cave, and thus the world was once again covered in radiant sunlight.

Hachiman: the Japanese god of war and archery

Hachiman (also called Yahata no kami) epitomizes the syncretism between Shinto and Buddhism in early medieval Japan. Revered as the god of war, archery, culture, and even divination, the deity possibly evolved (or grew in importance) with the establishment of several Buddhist shrines in the country around the XNUMXth century AD.

To that end, in a classic example of cultural overlap, Hachiman the war kami is also revered as a bodhisattva (Japanese Buddhist deity) who acts as the steadfast guardian of numerous shrines in Japan.

As for his intrinsic association with war and culture, Hachiman was said to make his avatars convey the legacy and influence of burgeoning Japanese society. In that sense, mythically, one of his avatars resided as Empress Jingu who invaded Korea, while another was reborn as her son Emperor Ojin (circa late XNUMXrd century AD) who brought Chinese and Korean scholars back to his country. court.

Hachiman was also promoted as the patron deity of the influential Minamoto clan (circa XNUMXth century AD), who furthered their political cause and claimed the lineage of the semi-legendary Ojin. As for one of the popular myths, it was Hachiman who saved Japan during the Mongol invasions by unleashing a typhoon on the approaching fleet, which was later named kamikaze ("divine wind").

Inari: the Japanese deity of agriculture (rice), commerce, and swords

Regarded as one of the most revered kami in the Shinto pantheon, Inari, often depicted in dual gender (sometimes male and sometimes female), is the god of rice (or rice field), thus alluding to the association with prosperity, agriculture and abundance of products. As far as the former is concerned, Inari was also revered as the patron deity of merchants, artists, and even blacksmiths; in some mythical narratives, he is perceived as the progeny of Susanoo, the storm god.

Interestingly, reflecting the vague gender of the deity (who was often depicted as an old man, while in other cases, he was depicted as a fox-headed woman or accompanied by foxes), Inari was also identified with several other Japanese kami. .

For example, in Shinto traditions, Inari was associated with benevolent spirits such as Hettsui-no-kami (goddess of cooking) and Uke Mochi (goddess of food). On the other hand, in Buddhist traditions, Inari is revered as the Chinjugami (protector of temples) and Dakiniten, which is derived from the Indian Hindu-Buddhist deity of dakini or heavenly goddess.

Kannon: the Japanese deity of mercy and compassion

Speaking of Buddhist traditions and their influence on the native pantheon, Kannon is one of the most important Buddhist deities in Japan. Revered as the god of mercy, compassion, and even pets, the deity is worshiped as a Bodhisattva.

Interestingly, unlike the direct transmission from China, the figure of Kannon is probably derived from Avalokitêśvara, an Indian deity, whose Sanskrit name translates as "All-respecting Lord". To that end, many Japanese fans consider even Kannon's paradise, Fudarakusen, to be located in the far south of India.

In the religious and mythical scheme of things, Kannon like some other Japanese gods has its variations in the form of gender, thus broadening its aspects and associations. For example, in the female form of Koyasu Kannon he/she represents the child-bearing aspect; while in the form of Jibo Kannon, he represents the loving mother.

Likewise, Kannon is also venerated in the other religious denominations of Japan: in Shintoism he is the companion of Amaterasu, while in Christianity he is venerated as Maria Kannon (the equivalent of the Virgin Mary).

Jizo: Japanese guardian god of travelers and children

Another Bodhisattva among the Japanese gods, the ever beloved Jizo who is revered as the protector of children, the weak, and travelers. Belonging to the former, in the mythical narrative Jizo had a profound duty to alleviate the suffering of lost souls in hell and guide them back to the western paradise of Amida (one of the main Japanese Buddhist deities), a plane where souls are liberated. of karmic rebirth.

In a poignant plot of Buddhist traditions, unborn children (and young children who predeceased their parents) have no time on Earth to fulfill their karma, so they are confined to the purgatory of souls. Thus, Jizo's task becomes even more crucial in helping these child souls by carrying them on the sleeves of his robe.

As for Jizo's cheerful countenance, the good-natured Japanese god is often depicted as a simple monk who eschews any form of ostentatious ornaments and insignia, as befits an important Japanese god.

Tenjin: Japanese god of education, literature, and scholarship

Interestingly, this god was once an ordinary human named Sugawara no Michizane, a scholar and poet who lived during the XNUMXth century. Michizane was a high-ranking member of the Heian Court, but he made enemies with the Fujiwara Clan, and they eventually got him exiled from the court. As several of Michizane's enemies and rivals began to die one by one in the years after his death, rumors began to circulate that he was the disgraced scholar acting from beyond the grave.

Michizane was eventually consecrated and deified in an effort to appease his restless spirit and given the name Tenjin (sky god) to mark the transition. Students hoping for help in exams often visit Tenjin shrines.

Benzaiten: Japanese goddess of love

Benzaiten is a Shinto kami borrowed from Buddhist belief and one of the seven lucky gods of Japan; that she is based on the Hindu goddess Saraswati. Benzaiten is the goddess of things that flow, including music, water, knowledge, and emotion, especially love.

As a result, his shrines become popular places to visit for couples, and his three shrines in Enoshima are filled with couples ringing love bells for good luck or hanging pink ema (wish plaques) together.

Shinigami: Japanese gods of death or spirits of death

These are very similar to the Grim Reaper in many ways; however, these supernatural beings may be somewhat less frightening and came later on the scene as they did not exist in traditional Japanese folklore. "Shinigami" is a combination of the Japanese words "shi", which means death, and "kami", which means god or spirit.

Although Japanese myth has long been filled with different types of kami as nature spirits, Shinigami got their mention around the XNUMXth or XNUMXth century. Shinigami isn't even a word in classical Japanese literature; the earliest known instances of the term appear in the Edo Period, when it was used in a type of puppet theater and Japanese literature with a connection to evil spirits of the dead, spirits possessed by the living, and double suicides.

It was at this time that Western ideas, particularly Christian ideas, began to interact and mingle with traditional Shinto, Buddhist, and Taoist beliefs. Shinto and Japanese mythology already had a goddess of death called Izanami, for example; and Buddhism had a demon named Mrtyu-mara who also incited people to die. But once Eastern culture met Western culture and the notion of the Grim Reaper, this representation appeared as a new god of death.

Ninigi: the father of Emperors

Ninigi or Ninigi No Mikoto is commonly seen as Amaterasu's grandson. After a council of the gods in heaven, it was decided that Ninigi would be sent to earth to rule justly and equitably. So from Ninigi's lineage came some of the first emperors of Japan, and from there comes his attribution of calling him the father of emperors.

Uke mochi: goddess of fertility, agriculture and food

She is a goddess who is primarily associated with food, and in some traditions she is described as the wife of Inari Okami (therefore she is also sometimes depicted as a fox). Not much is known about her, except that she was killed by the moon god Tsukiyomi; the Moon God was disgusted by how Uke Mochi prepared a feast by throwing food from her various orifices.

After his murder, Tsukiyomi took the grains that Uke Mochi gave birth to and gave them new life. However, due to the fatal murder, the Sun Goddess Amaterasu separated from Tsukiyomi, so day and night are separated forever.

Anyo and Ungyo: the guardian gods of the temples

This pair of Buddhist deities are known as Nio benevolent guardians who guard the entrance to temples, often referred to as nio-mon (literally "Nio Gate") and represent the cycle of birth and death .

Agyo is typically depicted with bare hands or wielding a huge club, with his mouth open to form the "ah" sound, which represents birth; and Ungyo is also often depicted with bare hands or holding a large sword, his mouth closed to form the sound 'om', which represents death. Although they can be found in temples across Japan, perhaps the most famous depiction of Agyo and Ungyo is found at the entrance to Todaiji Temple in Nara Prefecture.

Ajisukitakahikone-no-Kami: Japanese god of thunder and agriculture

He is the son of Ōkuninushi, and the "suki" part of his name refers to a plow. He is famous because he also resembled his son-in-law Ameno-Wakahiko, and was mistaken for Ameno during Ameno's funeral. Outraged at being mistaken for the deceased, Ajisukitakahikone destroyed the mourning hut, where the remains then fell to Earth and became Mount Moyama.

Ōyamatsumi-no-Kami: warrior, mountain and wine god

Kokiji and Nihon Shoki differ on the origins of Ōyamazumi. The Kojiki states that Ōyamazumi was born from Kagutsuchi's corpse, while the Nihon Shoki wrote: that Izanagi and Izanami created him after giving birth to the gods of wind and wood. Regardless of the version, Ōyamazumi is revered as an important mountain and warrior god, and is the father of Konohananosakuya-Hime which makes him Ninigi's father-in-law.

Furthermore, it is said that he was so delighted at the birth of his grandson Yamasachi-Hiko, that he made sweet wine for all the gods; therefore, the Japanese also revere him as a god of winemaking.

Atsuta-no-Okami: spirit of Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi the mythical sword of Japan

It is the spirit of Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi, the most important and famous mythical sword in Japan. Worshiped at Nagoya's Atsuta Shrine, Atsuta-no-Okami could alternatively be Amaterasu's spirit. In Shinto mythology, the mighty sword is said to be imbued with the spirit of the Sun Goddess.

Konohanasakuya-Hime: goddess of Mount Fuji, of all volcanoes and earthly life

Ōyamatsumi's daughter, Konohanasakuya-hime, or Sakuya-hime, is the Shinto personification of earthly life; she is also the goddess of Mount Fuji and all Japanese volcanoes. When Ninigi met her, he fell in love with her almost immediately in the terrestrial world, but when he asked Ōyamatsumi for her hand, her eldest god offered Iwa-Naga-Hime her eldest and ugliest daughter. her. Because Ninigi refused that offer and insisted on Sakuya-Hime, he was cursed with mortal life.

Later, Ninigi also suspected Sakuya-Hime of infidelity. In a reaction worthy of her title as goddess of volcanoes, Sakuya-Hime gave birth in a burning hut, claiming that her children will come to no harm if they are true descendants of Ninigi, where neither she nor her triplets were born. burned at the end.

Sarutahiko Ōkami: Shinto god of purification, strength, and guidance

In Shinto mythology, Sarutahiko was the leader of the earthly gods Kunitsukami although initially reluctantly, he eventually relinquished control of his domain to the heavenly gods on the advice of Ame-no-Uzume, whom he later married. He was also the earthly deity who greeted Ninigi-no-Mikoto when the latter descended into the mortal world.

Hotei: god of fortune tellers. waiters, protector of children and bringer of fortune

His name means "cloth bag" and he is always shown carrying a large one; supposedly, the bag contains fortunes to give away. Some folk tales describe him as an avatar of Miroku, the Buddha of the future. He also often appears bare-bodied, with his baggy clothes unable to hide his protruding paunch.

Ame-no-Koyane: Shinto god of rituals and chants

During the episode Amano Iwato sang in front of the cave, prompting Amaterasu to slightly push aside the rock blocking the entrance. Mainly enthroned in Kasuga Taisha of Nara and the ancestral god of the historically powerful Nakatomi Clan, that is, the main family of the Fujiwara Regents.

Amatsu-Mikaboshi: The Feared Star of Heaven

He is a Shinto god of the stars and one of the rare Shinto deities to be decisively portrayed as malevolent. He does not appear in the Kojiki but the Nihon Shoki mentions him as the last deity to resist the Kuni-Yuzuri. Historians have theorized that Amatsu-Mikaboshi was a star god worshiped by a tribe that resisted Yamato's suzerainty. In some variant versions, he is also called Kagaseo.

Futsunushi-no-Kami: Japanese ancient warrior god of the Mononobe Clan

Also known as Katori Daimyōjin, Futsunushi is a Shinto warrior god and the ancestor god of the Mononobe Clan. In the Nihon Shoki, he accompanied Takemikazuchi when the latter was sent to claim ownership of the ground world. After Ōkuninushi relented, the duo eliminated all the remaining spirits that refused to submit to them.

Isotakeru-no-Kami: Japanese god of the home

He is one of Susanoo's sons and was briefly mentioned in the Nihon Shogi. In that account, he accompanied his father to Silla before the latter was banished to Izumo. Although he brought various seeds, he did not plant them; he only planted them after returning to Japan. Within the Kojiki, he is called Ōyabiko-no-Kami; today, he is worshiped as a god of the house.

Jimmu Tennō: The Legendary First Emperor of Japan

He is said to be a direct heir to Amaterasu and Susanoo. In Shinto mythology, he launched a military campaign from the former Hyūga province in southeastern Kyūshū and captured Yamato (present-day Nara Prefecture), after which he established his center of power in Yamato. The Kojiki and Nihon Shoki combined Jimmu's dynasties with those of his successors to form an unbroken genealogy.

Kumano Kami: syncretized as Amitābha Buddha

The ancient Kumano region of Japan (present-day South Mie Prefecture) has long been a place of spirituality. After the rise of Buddhism in Japan, the kami nature originally worshiped in Kumano was syncretized with Buddhist saviors such as Amitābha Buddha. In its heyday, pilgrimages to Kumano were so popular that the trails of worshipers are described as being akin to ants.

Yanohahaki-no-Kami: A Shinto folk god of home and childbirth

It is also attributed the power to eliminate calamities from homes, it is associated in the same way with labor and with brooms, since brooms remove dirt, that is, pollution from homes.

Yamato Takeru: son of the legendary twelfth emperor of Japan

Yamato Takeru was a formidable yet brutal warrior, who disliked his father. He was sent by the emperor to deal with various enemies, expeditions in which the prince was uniformly victorious.

After lamenting to the high priestess of the Ise Grand Shrine for his father's dislike of him, he was given the legendary sword Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi to help him on future expeditions. Yamato Takeru never became emperor and supposedly died in the 43rd year of his father's reign. After his death, the precious sword was placed in the Atsuda Shrine, where it remains to this day.

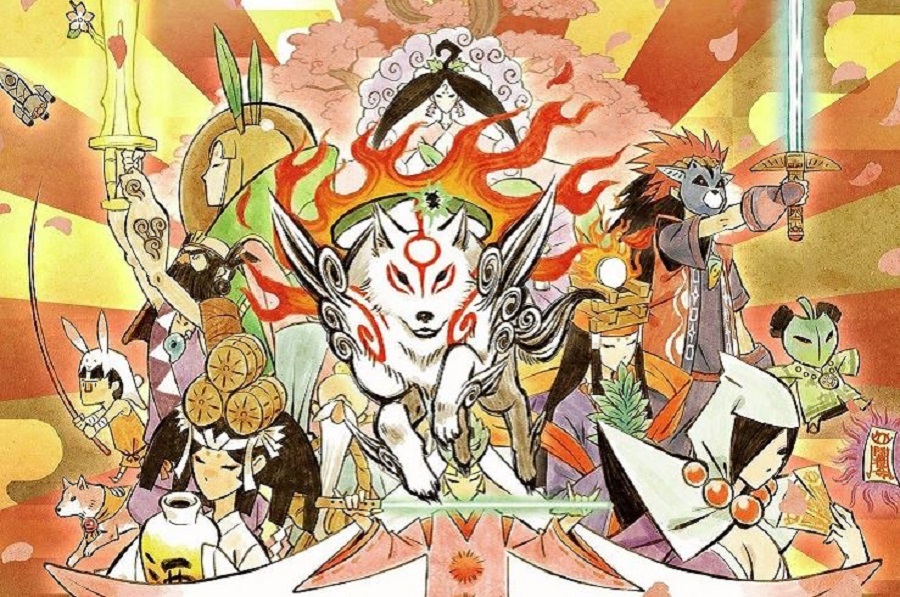

Shichi Fukujin: Japan's Famous "Seven Gods of Fortune"

These comprise deities from Shintoism, Japanese Buddhism, and Chinese Taoism. Historically, it is believed that they were "assembled" following the instructions of the Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu, with the purpose of representing seven types of blessed life.

Curious facts about the Japanese Gods

As part of knowing everything related to this topic about the Japanese gods, here are some interesting data:

- Buddhism, Confucianism, and Hinduism all had a tremendous influence on the mythical stories of the Japanese gods.

- The god Fukurokuji was believed to be the reincarnation of Hsuan-wu, a Taoist deity who was associated with good luck, happiness, and long life.

- In some Buddhist sects, Benten, the goddess of eloquence and patron saint of geisha, was associated with the Hindu goddess Saraswati (goddess of wisdom, knowledge, and learning). Saraswati was part of a trio of mother deities in Hindu mythology; the other two goddesses accompanying her were Lakshmi (the goddess of wealth and beauty) and Kali. (the goddess of power).

- The Japanese suffix no-Kami simply means "god" and is an honorific often tagged with names of Shinto deities.

- The suffix Ōmikami meaning "important god" or "main god". This honorific is only labeled for the most important Shinto gods. It is also often used to refer to Amaterasu, the most important Shinto sun goddess.

- Many Shinto gods and goddesses are given the suffix no-Mikoto. This indicates that the deities received some kind of important mission. For example, the settlement of the Japanese archipelago.

Relationship between Japanese Gods and Emperors

Most of the above entries are based on writings from the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki compendiums. In fact, many Japanese gods are not mentioned in other ancient Japanese texts; as within these two compendia, many are also mentioned in passing. As is obvious from the entries above, there is also a strong emphasis on lineage in both compendia; one that emphasizes that Japanese royalty, i.e. the Yamato dynasty, are the descendants of Japanese gods.

Both compendia are considered by historians to be pseudo-historical, meaning they cannot be trusted as historical fact because mythology and the supernatural are heavily weighted throughout the stories. However, as cultural and anthropological hints, the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki are invaluable. Where in addition, they suggest that the Yamato dynasty did not always dominate the Japanese archipelago and also give clues about the migratory movements within East Asia during ancient times.

If you found this article about the Japanese Gods interesting, we invite you to enjoy these others: