From Colombia we will talk about this indigenous group, today we will show you through this interesting article, everything about the Social Organization of the Muiscas, a Clan or extended family, related by blood ties. Do not miss it!

How was the Social Organization of the Muiscas?

The social organization of the Muiscas was based on the clan, which consisted of a group of people united by blood. The clans had a chief or chief, who could be a priest (also called a sheikh). Clans used to be part of a tribe, that is, several clans were united and formed a single social group. The social organization of the Muiscas had a stratification of social classes. Tribal chiefs, clan chiefs or priests held the highest social rank. They were followed by warriors (called guechas).

The next social class was made up of artisans, goldsmiths, potters, workers in the salt and emerald mines, merchants, and farm workers. Finally, in the lowest stratum, were the slaves. They were native enemies who had been defeated and then captured and forced to serve in the tribes.

It should be noted that there were many caciques within the social organization of the Muiscas. Those with the greatest power were called Zipas and Zaques and those with the lowest rank were called Uzaques.

Social Structure of the Muiscas

This indigenous group had a pyramidal social organization, formed by chiefdoms, priests, warriors, agricultural workers, artisans and merchants, and the lowest class: the slaves.

Domains

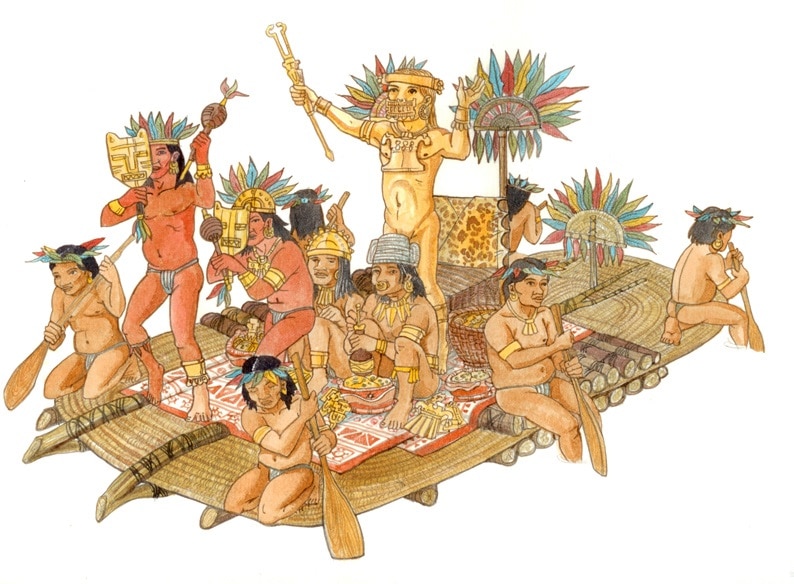

The Muiscas organized themselves into chiefdoms. They were political units headed by a cacique, who was the central figure of the organization. The caciques were accompanied by sheikhs, an entourage and town criers. The Muiscas considered the most powerful chiefs and the sheikhs as direct descendants of the gods. Chieftains and sheikhs were given the power to provide food for the community. To do this, they performed rituals in honor of nature, to protect them and to do anything supernatural.

For this reason, the caciques (zipas or zaques) could not be looked into their eyes and everything they produced was considered sacred. We speak of caciques of greater power, because there were other "caciques" who reigned locally (generally they were guechas who were named caciques for their actions in combat). These caciques were called uzaques.

Therefore, to keep the city under the rule of a supreme ruler, it was necessary to use town criers. The town criers were in charge of addressing the local caciques, reminding them that those who had the most power were these descendants of the gods.

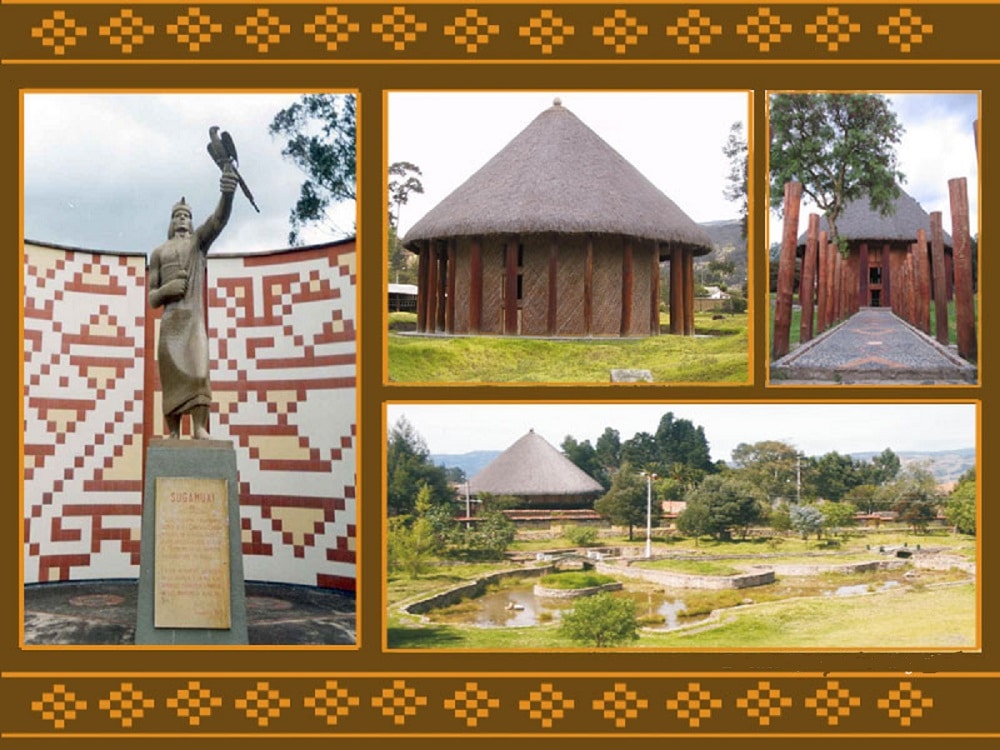

sacred headquarters

There were two sacred headquarters that had religious power, they are:

-The Sacred of Tundama, located in what is now known as Duitama, Paipa, Cerinza, Ocavita, Onzaga and Soatá.

-The Sacred of Iraca, located in what is now known as Busbanzá, Sogamoso, Pisba and Toca.

The Chiefdom of Guatavita

The Guatavita cacicazgo was formed in the XNUMXth century and inhabited the central part of the region occupied by the Muiscas.

The chiefdom of Hunza

The chiefdom of Hunza developed in what is now known as Tunja, a municipality in the department of Boyacá. The most important Hunza chiefs were: Hanzahúa, Michuá and Quemuenchatocha. Quemuenchatocha was the leader who was on the throne when the Spanish arrived, he insisted on hiding the treasure from him to protect it from the Spanish.

The Bacatá Chiefdom

This chiefdom developed in the territory of Zipa. The main Zipas were: Meicuchuca (considered by some historians to be the first Zipa of the Zipazgo of Bacatá), Saguamanchica, Nemequene, Tisquesusa and Sagipa. The latter was Tisquesusa's brother and succeeded to the throne after Tiquesusa's assassination by of the Spanish.

Sheikhs or Muisca priests

The Muisca priests were called sheikhs. These had a twelve-year education directed by the elders.

The sheikhs kept all the religious ceremonies active and were part of one of the most relevant social strata, since they considered themselves descendants of gods or astral deities. Therefore, all religious activities were taken very seriously.

The priests, like the chiefs of the tribes, were the ones who kept part of the tribute collected and the surplus harvest.

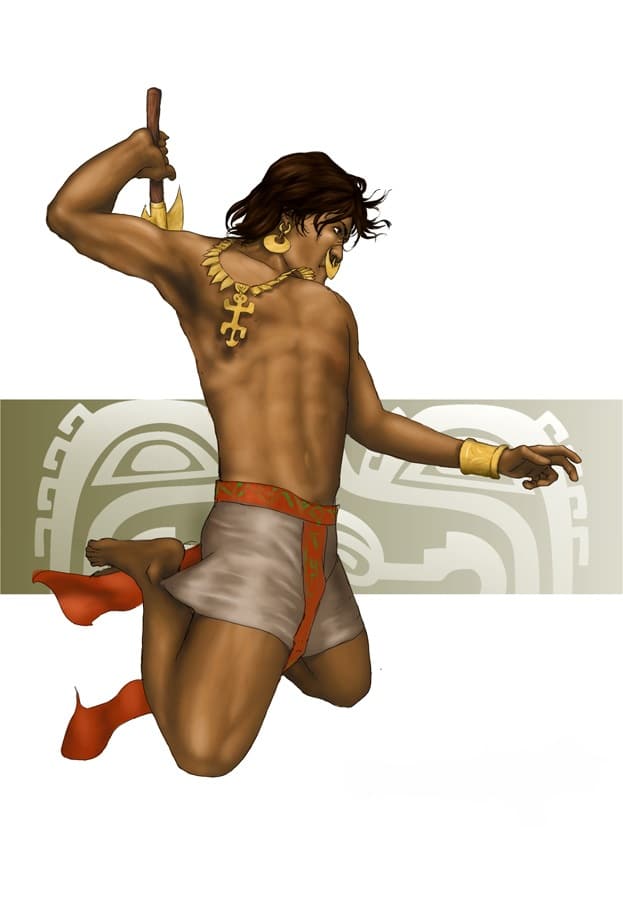

The muisca warriors

Muisca fighters were known as guechas. These were the ones in charge of defending the territory of the Muiscas against the enemy tribes.

The Muiscas organized themselves politically and administratively through the Muisca Confederation, which was made up of four territories: Zipazgo de Bacatá, Zacazgo de Hunza, Iraca and Tundama.

To be part of the guechas it was not necessary to belong to the nobility, the only thing that was needed was to demonstrate the strength and courage they had. The gechas were praised for their exploits in wars with other tribes and received the highest honors.

Muisca artisans and workers

This group was in charge of producing all the handicrafts, jewelry and ornaments used by the Muiscas. They were also responsible for working in the mines and working in the fields (harvesting all the food).

This group was the one that did the hard work, that is why it is said that without them the nobility, priests and warriors could not live.

The slaves

The Muiscas were in constant war with other tribes. In each of them, they defeated their enemies and took the survivors as slaves.

The slaves were in charge of carrying out certain tasks that the Muiscas entrusted to them and they had to live according to their orders.

How did the Muiscas get to the Throne?

The Muiscas had matrilineal succession rules. Thanks to this system, inheritance was granted through the mother.

Thus, the sons of a zaque or a zipa were not always the first in the line of succession. If there was a man who was a maternal father, he would be the one who had a right to the throne.

Customs and ways of life

Agriculture and food: The Muiscas have established scattered agricultural plots in various climatic areas. In each area they had temporary accommodation, which allowed them to enjoy agricultural products from cold and temperate zones in regulated periods of time.

This agricultural system, called the "microvertical model", was administered directly or through relations of homage and exchange with other indigenous ethnic groups to which the Muiscas had been subjected.

This model would be an adaptive response to ecological constraints, since most crops are annual. In addition, the constant risk of hail and frost, although it does not imply the total loss of crops, could cause shortages.

Part of the problem was solved with the many potato varieties that existed, plus most of these varieties could withstand frost within five months of being planted.

But also, by having products of different thermal levels, they had full access to sweet potatoes, cassava, beans, peppers, coca, cotton, pumpkin, arracacha, fique, quinoa and red beech, although the staple of their diet is corn.

As the Muiscas did not know iron, they worked the land with stone or wooden implements in the rainy season, when the soil softened, so they considered the dry season a great calamity.

Potatoes, corn and quinoa were the main consumption products, seasoned with salt, chili peppers and a wide variety of aromatic herbs. Twice a year, they harvest potatoes and corn once in the cold lands, where most of the population lived.

It is not known if they used the sweet corn stalk extract, as the native Mexicans did, or just honey, which was abundant on the slopes of the mountain range. The quintessential drink of the Muiscas was chicha, an alcoholic beverage fermented from corn.

They practiced hunting and fishing, the latter in the rivers and lagoons of the plains with small nets and reed rafts that they continued to make until the XNUMXth century.

They also consumed abundant vegetable proteins such as peanuts, beans and coca, and animal proteins such as curi, deer, rabbit, fish, ants, caterpillars, birds and forest animals. The Muisca authorities were in charge of the redistribution of food in times of scarcity.

The Spanish chronicler Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo has said that during the two years of the conquest, on no day were all the supplies needed to enter the Christian caves lost. He recounts that there were days of a hundred deer, others of a hundred and fifty and on the last day thirty deer, rabbits and a curious social organization of and even a day of a thousand deer.