Cats are one of the main pets that a human being can have and like all living beings, they need to take care to prevent them from contracting diseases such as intestinal parasites. If you want to know a little more about what these parasites that attack cats are, we invite you to continue reading this article.

Intestinal parasites in cats

Intestinal parasites in cats are a series of infections that occur in these animals, mostly due to ingesting some kind of food or object in the environment. There is a wide variety of these problems, however, it can be said that most parasitologists agree that intestinal parasites in cats, in particular helminths, have received less attention as pathogens or as possible causes of zoonotic diseases humans than their canine counterparts.

This is due in part to the perception that many feline internal parasites, particularly Toxocara cati and Ancylostoma spp. they are rare. However, the few fecal analyzes and necropsies that have been performed on cats in the United States do not support this assumption. In fact, the results of these studies indicate that feline roundworms and hookworms represent the most common internal helminth parasites of cats, regardless of the geographic region in which they were performed.

It is also interesting that although effective anthelmintics have been available for many years, the global prevalence of feline internal parasites does not appear to have changed significantly. In this article, several potentially pathogenic parasites of cats are explained. Some of these can also cause disease in humans. This last point will be emphasized given recent initiatives by government agencies and professional associations to prevent the transmission of certain parasites from pets to people.

giardiasis

This type of cat disease is caused by a parasite called Giardia. This itself usually resides in the small intestine, although other exceptional problems in this place cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, it must be recognized that it is a dimorphic parasite, as it exists as a fragile binucleate trophozoite and a quadrinucleate cyst. The trophozoite adheres to the surface of the epithelial cells of the small intestine. In turn, encystment (cyst formation) occurs in the ileum, cecum, or colon.

Although the mechanisms of Giardia-induced disease remain unknown, evidence suggests that it is likely multifactorial, involving inhibition of border enzymes or other factors such as altered immune responses, nutritional status of hosts, presence of pathogens intercurrent and the strain of Giardia involved in the infection. Although many infected animals remain asymptomatic, the most common presenting sign is small intestinal diarrhea.

The stool is usually semi-formed, but can be liquid and is usually not bloody. In addition, they have been described as pale (often gray or light brown in color), foul-smelling, and containing large amounts of fat. Cats with these types of parasites may have poor body condition and weight loss. Vomiting or fever are not common presenting signs. As mentioned above, it is not unusual to find them present with other gastrointestinal diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease. Giardiasis is best diagnosed by fecal flotation using zinc sulfate.

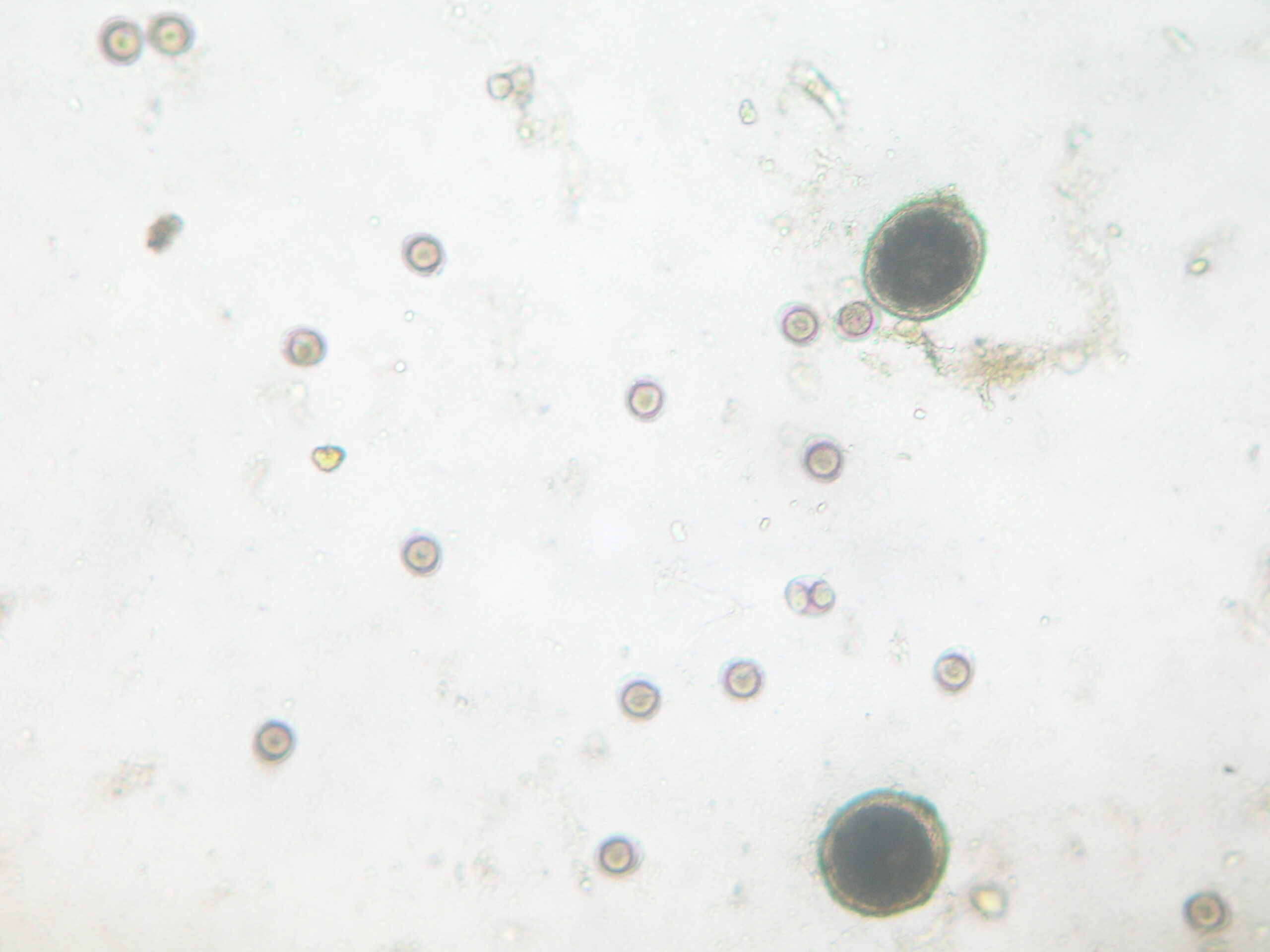

Centrifugation of the preparation increases the probability of recovering cysts. Also, adding a small amount of Lugol's iodine to the slide before placing the coverslip containing the concentrated cysts will help visualize small cysts (10-12 um). The use of barium sulfate, antidiarrheals, or enemas before stool sampling may interfere with cyst detection and should be avoided if possible. Other diagnostic techniques that can be used to recover trophozoites, cysts, or proteins produced by the parasite include direct stool examination (wet mount), immunofluorescent procedures, and ELISA techniques.

coccidial

These types of parasites in cats are caused by Isospora or recognized as Cystoisospora. They reside in the posterior small intestine or in the large intestine depending on the species. Their life cycles are usually self-limiting, after which the infection goes away. The parasites first replicate asexually through schizogony, resulting in the destruction of many enterocytes in the host in which they develop. Asexual development is followed by the production of gametes that fuse to produce noninfectious oocysts that are passed in the feces.

Developmental cycles in the feline host require from four to 11 days, depending on the species. Growth to the infective stage (sporulation) generally requires one to several days in the animal's environment. Only sporulated oocysts are infectious for susceptible hosts. Clinical signs of coccidiosis include bloody or mucoid diarrhea, abdominal pain, dehydration, anemia, weight loss, vomiting, as well as respiratory and neurological signs.

Death can result in extreme cases, especially in young kittens. During lactation, those who are recently weaned or who are immunosuppressed are more likely to develop this problem. Diagnosis of coccidiosis is based on signaling, clinical signs, and recovery of oocysts in feces. Fecal flotation remains the most convenient way to recover oocysts. A point to remember is that the recovery of oocysts in the stool alone is not sufficient evidence to implicate coccidia as the cause of the clinical signs.

Toxocara cati or roundworm

It is the most common intestinal nematode in cats and, according to many, the most important. These are the largest intestinal parasites in cats (3-10 cm) and resemble the canine roundworm. The few prevalence studies that have been done on cats in the United States indicate that this is generally the most common. For example, this disease was present in 43 percent of 60 cats surveyed in Kentucky and Illinois and in 92 percent of 13 control cats purchased for the Arkansas deworming study.

Researchers at Cornell University performed fecal exams on shelter cats and privately owned cats. The combined prevalence of these intestinal parasites in cats in the two populations was 33 percent of 263 cats. The prevalence in shelter cats was 37 percent. Surprisingly, the prevalence in deprived cats was 27%. Although some studies indicate that young cats are more likely than adult cats to sustain overt infections, other sources indicate that cats remain susceptible to infections throughout their lives.

These intestinal parasites in cats can be contracted in several ways: ingestion of embryonated eggs, ingestion of transport hosts such as mice, birds, cockroaches, and earthworms, and by transmammary transmission from the queen to her kittens. The transmammary route is apparently quite common. This disease undergoes a liver-lung migration, typical of other ascaridoid nematodes, before establishing itself in the small intestine. The developmental period in cats varies depending on the route of infection and host factors such as age.

Adult worms are productive egg producers, estimated to produce up to 24.000 eggs per day. The eggs take three to four weeks in the environment to become infective and can remain viable in the soil for months to years. Kittens infected with this problem may show signs of infection similar to puppies of dogs infected with the canine version, namely an enlarged abdomen and slow growth. Vomiting and diarrhea were also observed.

Infections can also cause lung damage, as well as signs such as coughing and sneezing as a result of parasite migration through the lungs or upper respiratory tract. Migration through the liver appears to occur without adverse effects. It is important to remember that these intestinal parasites in cats, like other roundworms, can also cause disease in humans, especially in children who accidentally ingest embryonic eggs from contaminated environments.

The resulting pathological syndromes are known as larva migrans. Visceral larva migrans (VLM) is caused by larval migration through internal organs and can lead to pneumonia and hepatomegaly, accompanied by eosinophilia. MLV usually occurs in children younger than 3 years old. In older children (usually ages 3 to 13), a second syndrome, called ocular larva migrans (OLM), can lead to serious eye damage and retinal detachment, vision loss, and even blindness.

Interestingly, recent studies in a laboratory animal model of human eye disease indicate that cat disease has the ability to cause eye disease in laboratory animals that is roughly equivalent to that of dogs. The diagnosis of infections by this feline pathology is confirmed by recovering the typical non-embryonated eggs in the feces. The eggs are smaller than those of the dog, but are structurally similar to them.

Hookworm

These intestinal parasites in cats are small worms (5-12 mm) that live in the small intestine. Which has a life cycle and pathogenicity similar to that of the common hookworm in dogs. In turn, it can be noted that it occurs geographically widely, while the Brazilian version is limited to the tropical and subtropical regions of the world. Additionally, many veterinarians believe that hookworms are not a common or significant cause of disease in cats.

Unfortunately, neither of these assumptions is always true. Some studies indicate they got the parasite from 75 percent of 60 cats in Illinois and Kentucky. In the other study cited above, this intestinal parasite was present in 77% of cats tested in Arkansas. In this location, its prevalence was surpassed only by the earlier parasite explained above. In turn, at a center in Alabama, 52 cats have been examined to date.

So far, 27 percent of cats and 23 percent of Toxocara have been recognized for the parasite. Interestingly, seven cats harbored the two parasites. Additionally, these parasites have been found in some between the ages of 1 and 6 and not just kittens, as one might suspect. On the other hand, cats acquire hookworms through various routes of exposure. They can become infected by ingestion of infective larvae, by skin penetration, and by consumption of transport hosts containing tissue larvae.

Additionally, it can be said that apparently in cats there is no transmammary or transplacental transmission of hookworms. Hookworm larvae in these mammalian animals migrate through the lungs prior to maturation into adult worms in the small intestine. The complete life cycle requires three to four weeks, depending on the type of infection that is detected or carried out.

Studies have shown that this parasite can cause hookworm in cats. Experimental infections can cause weight loss and anemia in infected cats. Depending on the rate of exposure to infective larvae, the result can be reduced hemoglobin levels, reduced packed cell volume, or death. The number of worms recovered from infected cats is usually not high. In one study, an average of 100 worms per cat was all it took to cause death in 16 cats.

Apparently the Brazilian version is less pathogenic than the common one. Experimental infections with tropical have failed to induce clinical disease similar to that described for A. tubaeforme. However, the brazilian is the species of hookworm responsible for the majority of cases of progressive eruption, a condition characterized by serpiginous dermal lesions in humans following the penetration and migration of hookworm larvae.

tapeworms

Tapeworms (cestodes) have long, flattened bodies that resemble a ribbon. The body is made up of a small head connected to a series of segments that are filled with eggs. The adult tapeworm lives in the small intestine with its head embedded in the mucosa. As the segments farthest from the head fully mature, they are shed and passed in the feces. These can be seen near the cat's tail and rectum or in the feces.

The segments are about a quarter inch long, flat, and resemble grains of rice when fresh or sesame seeds when dry. When they are still alive, they generally move by increasing and decreasing their length. Microscopic examination of fecal samples cannot always reveal their presence, because the eggs are not expelled individually, but as a group in the segments.

Although the discovery of this may be alarming to owners, infections rarely cause significant illness. Additionally, it can be said that cats generally become infected with tapeworms by ingesting infected fleas while grooming themselves or by eating infected rodents. Which obtained this disease by consuming the eggs of these parasites found in the environment.

stomach worms

These types of parasites in cats include the species of Ollanulus tricuspis and Physaloptera, which are worms that can inhabit the feline stomach. Ollanulus infections occur only sporadically in America and are most common in free-roaming cats and those housed in multi-cat facilities. Cats become infected by ingesting the parasite-laden vomit of another cat.

Chronic vomiting and loss of appetite may be seen, along with weight loss and malnutrition, although some infected cats show no signs of illness. Diagnosis of Ollanulus infection can be difficult and depends on the detection of parasite larvae in the vomit. The most effective treatment is unknown; avoiding exposure to another cat's vomit is the most effective means of controlling infection.

Physaloptera infections are even rarer than Ollanulus infections. Adult worms attached to the stomach wall excrete eggs which are then ingested by a suitable intermediate host, usually some species of cockroach or cricket. After further development within the intermediate host, the parasite can cause infection when the insect is ingested by a cat or by another animal (a transport host), such as a mouse, that has eaten an infected insect.

Additionally, it should be noted that cats with this type of pathology may experience vomiting and loss of appetite. Diagnosis is based on microscopic detection of parasite eggs in feces or observation of parasite in vomit. In turn, effective treatment is available and infection can be avoided by limiting exposure to intermediate and transport hosts.

Heart worm

This type of parasite in cats produces a pathology that is very rare to see in these animals, but its incidence is increasing, especially in some parts of North America. Heartworms are transmitted by mosquitoes. Which feed on a cat and through it, can infect heartworm larvae in the bloodstream. These larvae mature and eventually travel to the heart, residing in the main vessels of the heart and lungs.

In this animal, the signs of infection are not specific. Illness caused by these intestinal parasites in cats can cause coughing, rapid breathing, weight loss, and vomiting. Sometimes a cat infected with heartworm dies suddenly and the diagnosis will be made by post-mortem examination. Also, it can be noted that they are large worms, reaching 15 to 36 cm (6 to 14 inches) in length. They are mainly found in the right ventricle of the heart and adjacent blood vessels.

Treatments for intestinal parasites in cats

There are several options available for the control of giardiasis. Cats are best treated with metronidazole as directed. The use of metronidazole in cats is generally safe if the total daily dose remains below 50 mg per kg. On the other hand, it can be noted that other attributes of this type of drug are its antibacterial effects, activity against other protozoa and possible immunomodulatory effects.

In turn, it can be said that there are few studies to document the effect of benzimidazole anthelmintics such as fenbedazole against Giardia in cats. However, fenbendazole given at 50 mg per kg daily for XNUMX to XNUMX days, which is recommended for giardiasis in dogs, is also likely to be safe and effective in cats. Veterinarians now have a vaccine available to help control feline guard disease.

Based on available data, vaccinated cats are less likely to be infected with Giardia than unvaccinated cats. In addition, if they contract these parasites while being vaccinated, the diarrhea they present will be less severe and they eliminate fewer organisms during a shorter period of time. Veterinarians must evaluate each situation to determine if a particular animal or group of animals are potential vaccine candidates.

In the case of Coccidial, although sulfadimethoxine is the most commonly used drug in cats, several other agents have been used successfully. Little can be done to disinfect the environment due to the ability of oocysts to resist harsh chemicals and environmental conditions. Good sanitation, including prompt removal of faeces to prevent the development of infective-stage oocysts and treatment of queens with anticoccidial agents prior to farrowing, have been shown to reduce the occurrence of coccidiosis in young animals.

The best approach to control feline toxocarosis is to treat cats periodically to remove adult worms. There are several anthelmintics available for the elimination of T. cati. On the other hand, it should also be noted that those compounds with activities against other parasites such as heartworms as well as fleas are particularly attractive due to the need to control these parasites.

Several products are very effective against hookworms in cats. Prevention of predatory behavior in outdoor cats can reduce hookworm and roundworm infection levels, but this is difficult given the strong instinctive nature of this behavior. While keeping pet cats completely indoors can reduce exposure to worm parasites, this is difficult to achieve in many situations.

Regular or monthly treatment is the most effective way to control internal parasites. On the other hand, it may be noted that the latter is more easily justified now that some types of available medications make claims about heartworm or flea prevention or control and the various cat parasite specialists are more likely to use the products to prevent or control these pathologies.

For their part, modern medications are very successful in treating tapeworm infections, but reinfection is common. Controlling flea and rodent populations will reduce the risk of tapeworm infection in cats. Some species of tapeworm that infect cats can cause disease in humans if the eggs are accidentally ingested; but good hygiene virtually eliminates any risk of human infection.

Can they infect people?

Humans can be infected with both Toxocara and Dipylidium caninum; however, the latter is very rare and requires the ingestion of an infected flea. The first one mentioned is more concerning, as ingestion of the eggs can lead to migration of worm larvae through the body and possible damage. Due to the potential risk to human health and possible poor health of the cat, it is important to deworm cats regularly. Additionally, it is important to carefully remove litter from litter boxes and ideally the box should be sanitized weekly with boiling water.

If you liked this article about Intestinal Parasites in Cats and want to learn more about other interesting topics, you can check the following links: