In the highlands and valleys of the Colombian eastern mountain range, it gave birth to a civilization called Muisca or Chibchas, also known as the founders of the legend of El Dorado. Next, we invite you to learn a little more about the Muisca culture, their customs, religion, location and more.

Muisca culture

The Muisca or Chibcha culture is a native population that lived in the Cundiboyacense plateau and the southern territory of Santander (in the present region of Colombia), between the sixth century before our era. However, during the year 1600 the Spanish conquest came to dominate this town; At present, their immediate descendants reside in towns in the Bogotá district such as Suba and Bosa, and in other neighbors such as Cota, Chía and Sesquilé.

The word muyska represents "people" or "people" in the Muisca language. The Muisca culture is linked to a population of the Chibcha culture, which established the Muisca commonwealth. The Muisca forged gold coins using the tumbaga skill, which involves applying a higher proportion of copper to the gold alloy.

The axis of the region that today represents the Republic of Colombia, and which was previously called the New Kingdom of Granada, was occupied by peaceful and established indigenous peoples, agronomists and textile manufacturers, heirs of the Chibcha linguistic lineage originating from Central America. and who call themselves “muiscas” or “flies”. His homeland was the prosperous plains of:

- Zipaquira

- nemocon

- Ubate,

- Chiquinquira

- Tunja

- Sogamoso

Included among the sources of some tributaries such as: the Upía, which goes down to the Orinoco; Chicamocha, Suárez, Opón and Carare, which go to the north; of the Negro Cundinamarqués and Funza rivers that from northeast to southeast follow the Magdalena.

History

The pre-Columbian epic of the Muisca is in fact scarce, due to the destruction of a large amount of material that allows a specified reconstruction, due to the Spanish siege in the XNUMXth century. What is known about these pre-Columbian natives is the preservation of the verbal story, the stories of the colonialists and the archaeological works carried out especially after independence.

The muiscas, also known as muixcas or moxcas by the Spanish colonialists, resided in the central areas of present-day Colombia; however, the axes of its population were in the high valleys of the Sierra Oriental near Bogotá and Tunja.

The excavations carried out in the Cundiboyacense highlands region leave evidence of a great human movement in this space since the Archaic period, that is, more than 10.000 years ago at the beginning of the Holocene; this ended with a hypothesis considered valid in the XNUMXth century, according to which the Muiscas were the first inhabitants of the Altiplano.

Colombia also has one of the oldest archaeological sites on the continent, El Abra, which can be dated as far back as 11.000 years before our era. Other archaeological remains linked to El Abra determine an agricultural culture called Abriense. For example, in Tibitó Abriense artifacts dating back to 9740 years before our era have been found, and in the Sabana de Bogotá in the Tequendama refuge, other stone tools dating back a millennium, later made by specialized hunters.

Among the most beloved finds are complete human skeletons, dating back to 5000 years before our era. The analyzes showed that the Abrienses were another ethnic group different from the Muiscas, putting an end to the hypothesis that they occupied a desolate territory.

When the Spanish arrived around the year 1536, the Muisca culture had a population of approximately half a million natives. The natives of Cota were in Bogotá, one of the four commonwealths that constituted the political-territorial organization of the Muisca. The natives planted corn and hunted deer; These actions were complemented by the manufacture of textiles. Its usual social organization was governed by a model of matrilocal residence; They practiced consanguinity and matrilineality.

In 1538 after the initial armed battles, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada managed to fragment the alliance that existed between the Muisca leaders, thus easily subduing them. The Spanish invasion throughout the XNUMXth century led to the collapse of the socio-political organizations of the Muisca culture. In the XNUMXth century, the dialect of this city lost its unitary character and was displaced by Spanish; some local languages, however, have survived in the mountainous regions.

In principle, the conquerors subjected the Muisca chiefdoms to the encomienda system and later, at the end of the 1841th century, to the reservation system. The Cota reserve was dissolved in 1876, and was reconstituted in 2001 through the purchase of land. Today, the majority of the Muisca population is concentrated in the municipality of Cota, whose reservation of the same name was dissolved by Incora in XNUMX.

Currently, there are scattered remnants of these communities throughout the region who claim their ethnic origin. Various cultural foundations of the Muisca culture are maintained in the peasant societies of Boyacá and Cundinamarca.

Geographic location

The geographic area of the natives of the Muisca culture includes the towns of Cundinamarca, Boyacá and part of the south of Santander; the climate is changeable from the inclement cold of the stormy paramo of Sumapaz through the temperate plains, to the first foothills of the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy.

The central point of the area is the Cundiboyacense plateau, made up of a chain of plains, valleys and hills, intertwined by exuberant water deposits that cross rivers and ravines or are deposited in hundreds of lagoons, swamps and wetlands.

With elevations ranging from 2.500 to 2800 meters above sea level, and with mountains that can exceed 4000 meters in some places, the climate is cold and cool for most of the year. The rains rarely exceed 1000 millimeters in annual average. Devoid of volcanoes or snow-capped mountains, water has been the decisive element in shaping the landscape.

All the immense plains are seats of archaic lakes of the Pleistocene period leveled by leisurely sedimentation over tens of thousands of years. The largest of the plains is that of the Sabana de Bogotá, with more than 1200 kilometers that are completely flat and crossed by the Bogotá River (first called the “Funza River”).

Currently, this region is the one with the highest population density in Colombia, and everything seems to indicate that it was also one at the time of the Spanish conquest. The two main cities in this area are Bogotá, the capital of Colombia, and Tunja, the capital of the district of Boyacá; Both locations were initially created by the Muiscas.

The relief of the area inhabited by the Muiscas was mountainous, even in the middle zone dominated by the high regions of Simijaca, Ubaté and Bogotá. About two-thirds of its surface is made up of raised and steep areas, and another side is a respectively smooth and irregular surface. The landscape is framed by gigantic elevations that are fantastically linked to each other forming valleys, precipices, gentle slopes or sharp cuts in the rocks; climatic variations depend on height.

For millennia, the waters have made their way through narrow gorges where the liquid flows rapidly. Sometimes it collapses forming immense waterfalls and other times it slides slowly through the valleys, it can feed the lagoons or sometimes sweep the neighboring shores; it even manages to contain and then overflow, destroying everything in its path.

Features

The natives of the Muisca culture were and still are an agro-ceramic and manufacturing community, concerning the Andean territory of northern South America. The model of their political distribution transformed them into a resistant and trained cultural group. The contributions of the Muisca culture to Colombian self-identification in the present are indisputable, fundamentally because the Muisca commonwealth was nothing more than the highest political-organizational representation of a culture and a larger linguistic family.

Unfortunately, the Muisca population suffered an impetuous process of acculturation, manifested in the decline of formal aspects of culture; today, some natives are fighting to rescue some of the customs and notions of the world, in a process that seeks to restore the community to the splendor of the past.

Social organization

The base of the organization of the Muiscas, was the family. Weddings were generally celebrated between people of the own clan; the leaders had the exclusivity of having many spouses. The community was divided into different categories:

- Superior or usaques.

- Priests or sheikhs.

- Quechuas or warriors.

- Merchants and people linked to activities such as farmers, miners and artisans.

The priests or sheikhs were doctors and sorcerers; to achieve this position, the native had to study for many years.

Political-administrative organization

With the growth of the population, the Muisca culture implemented a method of administration designated as the Muisca Confederation, structured by several independent Muisca towns and governed by a cacique. In turn, the confederation was primarily assembled into two states:

Zipazgo

It constituted the Confederation of the South located in the central space of Cundinamarca whose capital was Bacatá, currently Bogotá, chaired by Zipa. It was also composed of five chiefdoms: Batacá, Guatavita, Ubaque, Fusunga, Ubaté, with several cities under his responsibility; With the conquest, most of these areas constitute Santa Fe de Bogotá.

zacango

The Northern Confederation was located in the present municipalities of Lenguazaque and Villapinzón with its capital in Hunza, which is currently Tunja, with Zaque as its leader. In addition to these spaces of the confederation, there were two great captaincies, with a more religious and sacred purpose called Zybin, these are:

- Iraq: Its capital Suamox, at present Sogamoso, was presided over by a priest or Iraca, considered as the successor of Bochica.

- Tundama: Established in Duitama, and led by a priest or Tundama, who was the only one to firmly oppose the Spanish conquerors.

There were different independent Muisca or Uta populations, represented by the Tybaraüge, who were not centralized under the same chief:

- Soboya,

- Charala,

- Chipata,

- Saquence,

- tacasquira,

- Tinjaca.

Lifestyle

During the development of the XNUMXth century, the Muisca natives welcomed a country way of life; This is how what was proper and traditional disappeared, such as: the dialect, the clothing and many traditional native customs. With the imposition of Catholicism, the Muisca religion perished; however, certain of its peculiarities still persist syncretically and are more associated with superstitious beliefs.

Locker

The Muisca textile manufacture manipulated an immense variety of fibers; especially those of cotton and fique. According to Chibcha custom, Bochita, the Muisca deity of civilization, instructed his believers to wind and spin filaments. In the houses of all the natives there was no lack of a loom, a reel and threads to make their own fabrics.

According to some settlers, the native villages were dressed in clothing of different shades on various special occasions. The attire consisted of a type of cloak and a blanket tied at the ends of the shoulder, made of thick cotton fabrics, adorned with colored stripes.

The most significant people wore thinner layers of different shades, the fabrics were stamped with nuances of vegetable and mineral nature, they used cylinders and porcelain stamps; they didn't wear shoes. They painted their bodies with achiote, they also used colorful bird feathers on their heads; they also wore beautifully crafted gold bracelets, necklaces, nose rings, and pectorals.

Economic activity

At the beginning, this ethnic group managed to develop agricultural activities, goldsmiths and textiles. They planted corn, potatoes, quinoa, cotton and made ceramics and blankets, which they marketed with nearby cities; later, with the Muisca Confederation, they exploit mineral resources such as: gold, emeralds, copper, coal and salt.

The market was the point of the Muisca economy, a place of commercialization or exchange of goods with the villages. Among the first there were: Coyima, Zorocota and Turmequé.

Another significant point of these natives is that they used a certain kind of coin molded of gold, silver or copper; the monetary value of this, was given by its size, measured with the fingers or a rope.

In addition, they established an agricultural system called the micro-vertical model, which had temporary houses in each area and worked the land according to the weather; this represented a solution for the cultivation against the limiting climatic conditions of the region.

Religion and beliefs

The religious particularity of this ethnic group is that they considered that the spirits were linked to nature, which is why they consecrated many sacred places that, according to their dogmas, were marked by a deity, among them we have:

- Sacred Woods: they were sacred and therefore should not be manipulated in any way, motivated by their belief in being blessed by the gods.

- Sacred plants and trees: such as tijiqui, tobacco, blueberry, walnut and guayacán.

- sacred lagoons: Iguaque lagoon and Lake Tota, as well as those that belonged to the circuit of the religious ceremony to make the land work, such as: Ubaque, Teusacá, Guaiaquiti, Tibatiquica, Siecha, Guasca and Guatavita, traveled by the pilgrimage participants.

- Sacred land of Suamox: Estimated as a blessed space, because Bochica died there.

- sacred avenues: are those paths in which Bochica walked, no individual could walk on them, except in certain religious ceremonies.

- Temples: circular foundations with thatched roof and mat walls. Among the types of temples, one distinguished the tchunsua of solar nature, qusmhuy of lunar essence and the cuca where the future chyquy was taught.

The sanctuary of the Sun, the largest of the religious centers, was erected in Sogamoso, an area selected by Bochica in homage and esteem for the god of the sun; to whom they gave the bodies of those who were offered there.

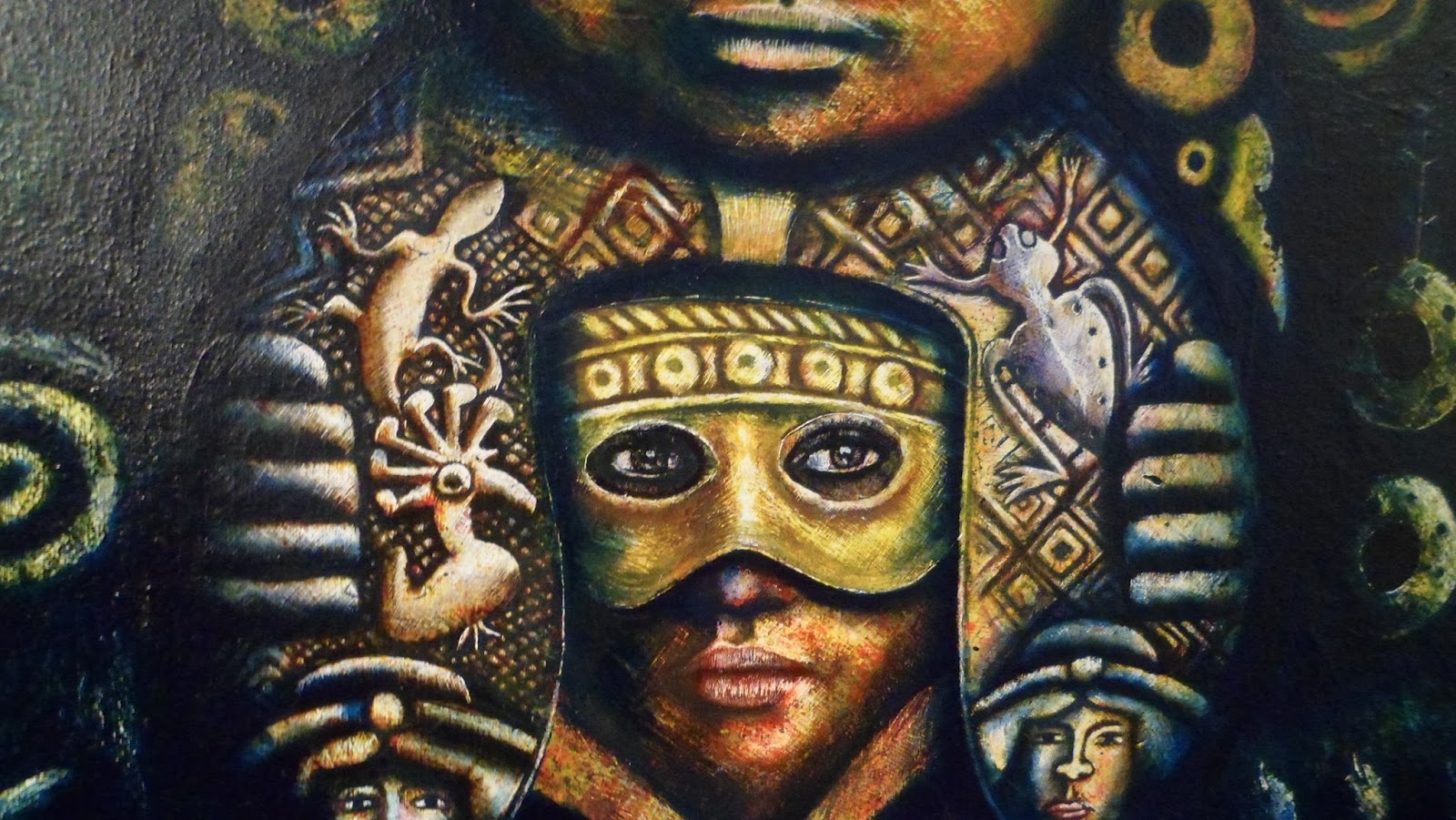

They also worshiped a series of mythological deities such as Bachué (first-born of the town), Bochica (son of the sky), Chaquén (watched over crops), Chibchacum (god of goldsmiths and merchants), Chiminigagua (creative deity), Chía (god of the moon) and Sua (god of the sun).

The Muisca or chiky priests led a religious life of celibacy, chastity and seclusion in the sanctuaries with frequent fasting; these had a difficult process of instruction from their childhood, that once they were completed they were placed with gold earrings and nose rings. It is important to note that each city had its chyquy. On the other hand, the mohanes were informal priests who inhaled iodine powder and covered their hair with ashes.

The rituals and ceremonies

Like all pre-Columbian cultures, the Muiscas made different offerings to their gods, among which the tunjos stood out. They were anthropoid figures or animals in gold, silver or copper; other forms of offering to the gods were incense sticks, animal and human sacrifices, such as that of young women, who once sacrificed themselves, smeared their blood on the stones to offer them to the sun.

Essentially, the ceremonies of the Muisca culture were related to agricultural cycles and life; these contained cultivation and harvesting festivities, caiques, the building and opening of fences.

Bus Routes

Through the network of Andean roads of the native villages of Colombia, individuals, goods and products were moved on foot and back, using immense highways, rope bridges and canoes or wooden rafts.

Communication

During pre-Columbian times, the natives announced some information carried through chasquis, which communicated and traveled long distances on foot, transported information between societies or used signaling systems with which they managed to communicate at a distance.

Medicines

A health condition obtains a magical representation and its causes must be battled by the native priest doctor, with magical techniques; The magical character thrown at the shaman or the sheikh is manifested by the use of hallucinogenic substances and the correct administration of coca powder or iodine, considerably handled by the Muiscas.

Time and space

The natives of the Muisca culture calculated time through an almanac similar to the one we are familiar with today; however, the days were dominated as follows:

- The day was called sua.

- A group of three days was called sunas.

- Ten Sunas made a month, they represented it as sunata.

- The year was made up of twelve months of ten sunas each.

Architecture

The Muiscas raised their homes using sticks and mud as main components, finally making the walls of bahareque. The usual houses had two models: conical and rectangular. They are detailed below:

- conical housings: it consisted of a circular wall formed by posts buried as more solid pillars on which a double was supported from side to side between a reed fabric whose interstice was full of mud; the roof was conical and covered with straws fixed on poles, the profusion of such conical constructions in the savannah of Bogotá, gave birth to Gonzalo Jiménez de Quezada giving this plateau the name of Valles de los Alcázares.

- rectangular houses: they were based on parallel walls also in bahareque, like the previous one, with a roof with two rectangular wings.

The conical and rectangular buildings had doors and vents of a small size, inside the furniture was simple and resided primarily in beds also made of reeds or sticks called barbecues, in which a great profusion of blankets was developed; armchairs were insufficient as the natives used to squat on the ground.

In addition to the common dwellings, there were two other types of residences: one for the important lords, possibly the chief of the tribe and his clan, and others for the chiefs of the Muisca confederations, such as the zacques and the Zipas.

Ceramics

There were constructions destined to the activity of ceramics, such as Tunja, Tinjacá, Tocancipá, Soacha and Ráquira. They made receptacles for gifts in shrines, anthropoid figures representing their guardian deities and important figures, and huge vessels for trade.

They made their pottery by forming the clay directly or by means of spiral clay rollers; the decoration used was red and white paint in various shades, these colors were obtained from mineral oxides.

Some vessels were adorned with pastillage applications and incisions, a technique with which they produced anthropoid and geometric designs. Ceramic decoration was poor, except when the design had a magical-religious symbolization with snakes and human figures.

Textiles

The manufacture of textiles was of great value in the high and cold regions of Cundinamarca and Boyacá. The writer Fray Pedro Simón, describes the fact that the Muiscas used blankets of red pigments as an indication of mourning, the Indians of Lenguazaque used them in different shades of colors and the courtiers of Tunja very exuberant and decorated; Sugamoxies surrounded the corpses of their ancestors in cotton blankets.

A great variety of geometric patterns, apparently symbolic, were painted on these blankets, and thanks to the explorations of Eliécer Silva Celis, it is known that the mummy blankets are cotton fabrics, mesh fabrics and animal skins.

The weaving industry was of extraordinary importance to the Indians; all life events were celebrated with blankets. To decorate them, they used many plants as colorants, they also used dyes of mineral origin or earth-based colored clay species.

goldsmith

Goldsmithing has been perfected with varied and complex metallurgical techniques, such as working with tumbaga and lost-wax casting.

We can distinguish the beautiful anthropoid and zoomorphic representations of the tunjos or propitiatory offerings to the deities.

The variety of gold ornaments for chiefs and principal lords, and ornaments for residences were exhibits of great beauty; They also used copper, for the elaboration of anthropomorphic figures and ceremonial canes, and they made hooks, earrings, pectorals and other copper objects.

Legend of El Dorado

The Gold Route was the main reason why the Spanish expeditionaries reached unexplored and almost impregnable lands, founding cities on their way that today are still strong settlements with five centuries of history behind them.

El Dorado was not only a fantastic image, but it was also the engine that led to the discovery of new lands and the murder weapon that annihilated the native troops and their comrades.

They relate that the legend of El Dorado was originally mentioned in the excursions of Vasco Núñez de Balboa and that they culminated in the discovery of the Pacific Ocean, specifically in what currently concerns the Panamanian space.

It is at that time, where the natives of those lands mention the Spanish colonizers about a place of abundant gold, the magnitude of which was so great that they insinuated that it was practically inexhaustible and that it was to the west, in what we now call Colombia.

El Dorado motivated the mobilization of Spanish soldiers from the territories that are now known as Peru and Venezuela, and that had as a conjuncture the meeting of military commanders whose event gave rise to the foundation of the important Colombian cities of Cali and Bogotá.

All these fantastic creations of the natives and the Spaniards themselves were called "Dorado" and the first to be reviewed is that of the valley of the native Tayronas in the hills of the town of Santa Marta on the Colombian Caribbean coast; however, it did not possess the expanses of the so-called gold zone that ambitiously blinded many people from all directions.

The territory where the fable of El Dorado was built as a significant part of the tradition belongs to Cundinamarca, territory concerning the great native Muiscas or Chibcha lineage, in the present jurisdiction of the Republic of Colombia. It is in that place, Cundinamarca, that a rite was baptized by the Spaniards as that of the golden Indian, which was the origin of the belief in a golden kingdom.

For indefinite times, the indigenous peoples have worshiped a kind of sacred snake that appeared in the waters of the Guatavita lagoon, and according to oral tradition the Cacica with her daughter was thrown into this lagoon after the Cacique accused her of infidelity and he ordered the other natives to sing drunken songs related to his adultery, the chief could no longer bear this ordeal and decided to put an end to it under his waters.

The cacique fell into dark despair and the priests, to calm his tragedy, convinced him to believe that deep in the Guatavita lagoon his wife and daughter still existed and that they inhabited an enchanted palace. So this completely bathed in golden dust, was transported on a raft and in the middle of the lagoon, he threw articles of pure gold as offerings to his family.

Many have always doubted the accuracy of anything to do with this belief, but even when its veracity is questioned, these events embody one of humanity's deepest legends and fuel the adventurous spirit of wealthy Europeans.

If you found this article interesting Muisca culture, we invite you to enjoy these others: